A Spirit Garden for Alderville First Nation: Q&A with Terence Radford

Text by Glyn Bowerman

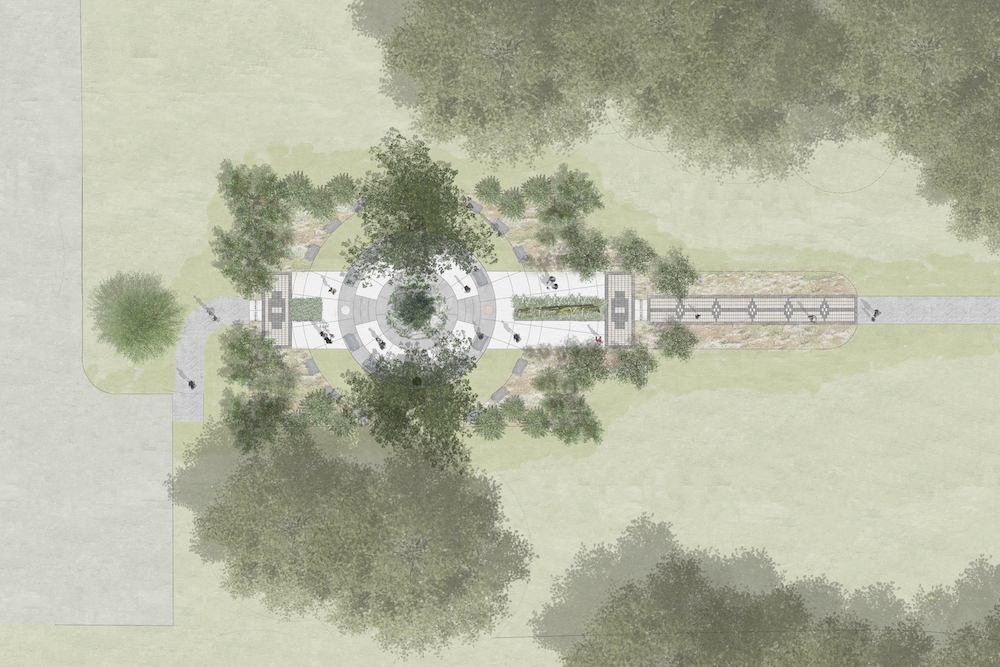

This summer saw the opening of a public art and landscape installation in Kingston, Ontario, meant to welcome the Alderville First Nation (residing in Rice Lake) back to their traditional territory. The City of Kingston worked with Alderville to find the appropriate commemorative site, space, and design. Métis landscape architect and artist Terence Radford was commissioned to work with the community to design the project, and the Manidoo Ogitigan, or Spirit Garden, was realized at Lake Ontario Park.

Glyn Bowerman: To begin, I wanted to ask how the Spirit Garden came together?

Terence Radford: The City of Kingston started conversations with Alderville First Nation around 2013. My understanding is Alderville originally came to them about the City being their traditional territory, Alderville’s history in that area, and how they ended up out in Rice Lake. They were originally talking about a plaque, and the City came back and said, ‘Look, we can do better than a plaque, let’s talk about a commemorative piece.’ So they worked with Alderville for four years about what this piece might be and where it would be located. They had elders and community members come out and look at a number of sites and landed on Lake Ontario Park as the preferred location. They put out requests for qualifications to get interest from artists, and shortlisted three in early 2018. I was one of the three chosen to do conceptual options.

We worked for a full year on that and had three meetings with Alderville. Two of them were smaller, mostly with the Chief, some council members, and members of the community. Then, we had one larger public open house at the community centre, where we each presented whatever we prepared and were given an opportunity for feedback from the larger community of Alderville. Then, we had time to revise before we did our final submissions in late 2018. They reviewed those and assembled a committee of Indigenous artists from across Ontario, Alderville Chief Dave Mowat, and community members. We moved into detail design and development of the artwork from the beginning of 2019, until the summer of 2020: refining the work in close communication with the community.

We reached consensus between the City and Alderville and were able to begin construction in the summer of 2020. We completed construction this summer in 2021.

GB: And this concept of a “spirit garden,” or Manidoo Ogitigan, is this a traditional First Nations idea?

TR: It was built into the original request for qualifications and the request for proposals (RFP) for the art piece, which the City worked on with the Alderville community when they wrote it. That’s kind of unique in itself: I don’t always see input from First Nations when RFPs go out, even when dealing with Indigenous content in public spaces. But they had consulted with the Nation on what was going into the RFP and what the vision for the art piece would be, and it outlined things like having a gathering space, and the importance of the environment being addressed in whatever the final artwork was.

So, when I applied with my initial concept, I wanted to do something that was more of a land-based artwork than a traditional sculptural form—both because I’m a practicing landscape architect, and because my work as an artist has heavily focused on the environment. All three artists had gardens, or components of the environment, built into their final piece because of the way the RFP was originally written.

But the piece itself isn’t a traditional form in any way. It’s really a byproduct of me learning about the history, my conversations with community members, and the fact that the Black Oak Savanna is such an important landscape in Alderville.

GB: How does the project speak to the history of Alderville First Nation?

TR: When I designed the piece, Chief Mowat, who’s an historian and worked for Trent University in Peterborough, provided us with some pretty extensive research and papers he wrote about the history of Alderville, which gave us a really good foundation for who the Nation was, their history in relation to the City of Kingston, and drove the incorporation of a lot of elements in the piece. Specifically, we incorporated three wampum belts into the artwork, heavily influenced by the research Chief Mowat conducted with regards to the importance of the 1764 Covenant Chain wampum belt and the Niagara treaty, as well as the Chief Yellowhead wampum belt. That belt talks about the extent of the territory of the Mishi Saagiig [Mississaugas], traditionally: the teaching that goes along with it talks about the seven council fires, and specific animal representatives associated with each nation that held one of these council fires. The final belt we chose was the Dish With One Spoon, after conversations with community members, who felt strongly about it.

There were also a number of teachings I received from elders, especially Rick Beaver, who was one of the key members I spoke with extensively over the years, which drove the preparation of things like the medicine wheel design in the paving. Then, there was the selection of plant material. I worked specifically with one member, and we built the planting plan together, based on her knowledge of plants native to the Black Oak Savanna typology. We picked plants we both knew would do well in the soil types and hydrology of the site, but would also fit in a very public area, and have some sort of aesthetic interest or specific teaching opportunity.

GB: A lot of engagement went into this project and, as you said, it’s unique when Indigenous communities are at the head of the table. Are there lessons here for the landscape architect profession?

TR: I only moved to Ontario in 2017. I am incredibly lucky that one of my first major projects after moving was making this commemorative public artwork with the Alderville First Nation. Part of me coming to Ontario and starting out on my own was that I had done work with First Nations communities, both as a landscape architect on the west coast, and within the Aboriginal Friendship Centre organization. I had experiences working with First Nations and Indigenous communities and organizations and I knew the types of conflicts that could arise. So, when I came out, I really wanted to work with communities again, but also address some of the barriers I had observed. And probably the biggest barrier is the timeline of a project. I give the City of Kingston a lot of credit because the timeline for completion was originally late 2018, but they realized that was not a realistic goal. They let the community take the lead—ultimately defining how long the engagement process was. It turned from a one-year long proposal/selection/construction process to a four-year one, and that was driven by Alderville, who we always looked to for the time and frequency of meetings. We were respectful of both their capacity for engaging on a project, as well as events in the community. Often, an elder or someone might pass away during a project, and that’s an event that often will stop work in a community while they conduct ceremony and go through personally processing the loss. We wanted to ensure we were respectful of events like that, and weren’t trying to push for something to be completed on our timeline, but work with them and keep open communication to realize a project they were really invested in and

felt ownership of.

GB: The theme for this issue is “Home.” I know home can be a fraught idea when we’re talking about colonized spaces, so I was wondering how you hope the Spirit Garden creates a sense of home for the Alderville First Nation, as well as general visitors to the park.

TR: That heavily drove the project. The City of Kingston was always devoted to the idea that the commemorative public artwork and space would become a new home for the community, while in Kingston. When we did our initial opening during the summer on National Aboriginal Day, the summer solstice, we spoke a lot about the space being a new home for Alderville in the City, and how the garden, gathering, and ceremonial space we created was welcoming for them—a home away from home. That was a very small gathering. But the sentiment was mirrored when we had a larger opening here in the fall, where we could bus out a number of people from the community, including elders who helped choose the site. The Chief and elders commented on the fact that the space made them feel at home when they were there, and they felt welcomed and safe. Our hope is we continue building that relationship with Alderville, continue bringing community members to this space, keep it as a home for them, and let that guide its development. Because it’s a living piece, and will require stewardship and guidance over the next several years.

One thing we weren’t counting on when we designed the piece, although it was a hope, was how the community in Kingston engaged with it. Queen’s University and St. Lawrence College (across the street from Lake Ontario Park) have both adopted it as an outdoor teaching and learning space: bringing classrooms out, especially when they have knowledge keepers visiting or presenting to the classes. We came out one day to do maintenance and there were 30 people sitting in the piece. We asked them who they were, and it was a geology class with a knowledge keeper from Tyendinaga teaching them.

BIO/ Glyn Bowerman is a journalist, editor, and podcaster in Toronto. He is the host of the Spacing Radio podcast, which focuses on urbanist issues in Canadian cities, and Ground Magazine editor.