Delving into the History of Edwin Kay, a CSLA Founder

TEXT BY RON KOUDYS, OALA, FCSLA

Edwin Kay was an interesting and influential man who helped shape the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects (CSLA) and what would eventually become the OALA, yet relatively little information is available about him on the public record. While attending a fundraiser, I met Katharine Wanger, Kay’s granddaughter, and she agreed to share family stories and information with me.

Edwin Kay was born in Whorlton, England, on June 1, 1889. After receiving his formal schooling, Edwin was sent to apprentice with the head gardener at one of the Queen Mother’s residences (Streatlam Castle) in the town of Barnard Castle. It was here that his knowledge of horticulture grew, and he developed a passion for roses. Over time, he took over as head gardener and became quite well known as an expert in the design and culture of rose gardens.

After his marriage to Evelyn Forshaw in 1913, Kay and his wife moved to Europe, where he took a position as head gardener at one of the German royal family’s castles. Their time there was short-lived, though, as the threat of war caused them to return to England.

In 1915, Kay was called up for service in the British Army. He was captured by the Germans and spent two years in a prisoner-of-war camp. On his release, he began planning to emigrate and, in 1920, he moved to Canada. Kay thought of himself as a professional landscape architect and set up a design office in Toronto at 96 Bloor Street West.

Kay’s practice did very well in the booming days of Toronto during the 1920s, and he completed many high-profile projects. He was one of nine landscape architects who regularly met at the Diet Kitchen Restaurant on Bloor Street and eventually formed the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects and Town Planners. Humphrey Carver (CSLA President in 1939), while speaking at the 50th-anniversary meeting of the CSLA in 1984, described Edwin Kay as “having a small moustache, a black suit and a watch-chain hung across his waist coat; Kay looked more like a businessman than the other more ‘tweedy’ members of the group. He belonged to the management side of landscape work and had the air of a practical man who knew how to get things done.” (Ken Phipps, A History of the Cawthra-Elliott Estate, September 1989.)

Kay undertook a number of projects for the City of Toronto, perhaps due to his excellent sense of politics and his strong connections at city hall. Some of these projects included the cuts for the TTC subway and the Alexander Muir Memorial Gardens. Fresh from winning a prize for his design of an Italian garden at the Canadian National Exhibition, Kay was selected by a committee to design a garden in memory of Alexander Muir (composer of the song “The Maple Leaf Forever”), originally located across the street from Mount Pleasant Cemetery, in Toronto. The construction of the Yonge subway line, in 1951, required that the gardens, gates, and stone walls be moved to their current location near Yonge and Lawrence, and Kay was hired to supervise the move.

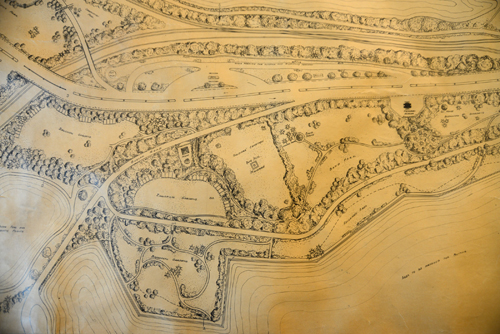

A few of his other projects included the estate of Governor-General Massey at Port Hope, the Dyer Memorial in Huntsville, the Cawthra-Elliott estate in Mississauga, the landscape surrounding the Shell Tower at the CNE in Toronto, and numerous private homes, many of which featured beautiful rose gardens.

Kay served as president of the CSLA, which had formed in 1934, for two terms: first in 1937 and then again from 1950 to 1952. In 1946, he appeared at Queen’s Park with Gordon Culham (first president of the CSLA in 1934, and again in 1956-58), expressing the CSLA’s concern that the professional engineers’ association had included town planning in their field as part of a new bill that was being considered by the Ontario legislature. They were able to point to a list of new town planning projects being carried out by landscape architects, while no projects were being designed by engineers. Today, this action seems particularly appropriate considering the OALA’s recent attempts to strengthen the place of landscape architecture with a Practice Act.

In 1948, Kay attended the inaugural Congress of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) in Cambridge, England. He went to a number of these international events and became a life member of IFLA. Following the first Congress, he wrote an article for the American magazine Landscape Architecture in which he discussed one of his greatest concerns: “…the student of today does not receive an adequate training in plant ecology and lacks generally the basic knowledge of the materials he has to work. It is one thing to know design, but design without proper execution is worthless.”

Kay’s focus on plants was also demonstrated by his commitment to the Men of Trees Society. The organization planted trees around the world, and Kay served as president of the Canadian branch. [See Ground 38, “Faith and Silviculture,” by Camilla Allen, for more information about the Men of Trees Society.]

In 1951, Kay was speaking as the president of the CSLA during the opening of Landscape Art Week at the Montreal Botanical Gardens, and he stated that Canada needed a landscape department in at least one of its universities. Francis Blue (one of the CSLA’s nine founders) wrote that the first move toward professional status occurred in 1952 when Edwin Kay “pointed out the desirability of protection by legislation for Landscape Architects similar to that enjoyed by the allied professions of engineering and architecture. The great drawback to this was the lack of a School of Landscape Architecture in Canada.” (Francis Blue, History of the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, unpublished manuscript.) Thirteen years later, in 1964, Victor Chanasyk, OALA (Emeritus), and Jack Milliken, OALA (Emeritus), helped to found Canada’s first school of landscape architecture at the University of Guelph.

Kay’s wife Evelyn died in 1951, and he married twice more before his own death on December 9, 1958. It must be said that Edwin Kay’s foresight and commitment to the profession of landscape architecture has left a legacy that we enjoy today. He demonstrated resilience and a passion that laid the groundwork for future generations. In his Landscape Architecture article, he wrote: “opportunities exist and are presenting them- selves daily in such a way as we have never before known… We, of the profession, shall be very remiss in our duties and obligations if we permit these opportunities to pass us by without exerting our every effort to cope with them in a masterly and professional manner.” This call to action is as applicable today as it was in post-war 1948. The contribution made by this important figure in the history of our profession should be recorded with those others who did so much to shape what the OALA is today.

BIO/ RON KOUDYS, OALA, FCSLA, ASLA, IS A RETIRED PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE DESIGN AT FANSHAWE COLLEGE AND MAINTAINS AN ACTIVE PRIVATE PRACTICE IN LONDON, ONTARIO.