Citizen Science: Lichen and air quality

Lichen is mysterious, even to those who specialize in studying it. Often mistaken for a plant, it is an association between a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium— although in 2016, scientists discovered that yeast is often part of the equation, too. “That was a shock to the lichen community,” says Carolyn Zanchetta, the Hamilton Naturalists’ Club’s resident expert on this strange, complex, and hard-to-identify life form. “I’ve collected a lot of bird poop accidentally,” says Zanchetta, “thinking it was lichen!”

I’m standing in an old cemetery in Hamilton with Zanchetta and a group of naturalists, learning about lichen. We’re participating in a citizen science project, Lichen in the City, initiated by the Hamilton Naturalists’ Club and Environment Hamilton to monitor lichen as an indicator of local air quality. You could call it “slow environmentalism” because there’s nothing instant about this study. And nothing instant about lichen.

We start with a biology lesson. Lichens grow extremely slowly—some species at just 1 mm a year. Tough and hardy, they can survive without water for a year (“they put life on pause,” says Zanchetta) and then start to photosynthesize when hydrated again. They’re one of the longest-living organisms known on earth, with a species in the Arctic clocking in at 8,600 years. Most lichens reproduce in the simplest of ways, just by breaking off—by wind, water, animal touch—and “re-rooting” elsewhere, though this term is misleading because lichen doesn’t have roots. Lichen can be found pretty much everywhere, from the Antarctic to the Arctic. Some species grow on rocks, some on bone. There’s a misconception that lichen kills trees—it doesn’t, though it can work its way into rock crevasses and cause deterioration. Some lichens look like small, branching shrubs, some like coral, some like hair, some like pins, some even look like Shrek’s ears or witches’ brooms. The variety of shapes and colours is incredible.

But the biological feature of lichen that has brought us all together on this early spring day in an old Hamilton cemetery is that lichen does not thrive in the presence of air pollution—in particular, sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxides. This makes lichen a useful biomonitor to infer ambient air quality. As McMaster professor George Sorger found, areas with a high lichen presence have better air quality than those areas with low lichen presence.

The project Lichen in the City has hosted a number of workshops in six Hamilton neighbourhoods to introduce community members to lichen identification. These citizen scientists then engage in lichen monitoring to gather a baseline of data that can be replicated in the future to assess changes in air quality over time.

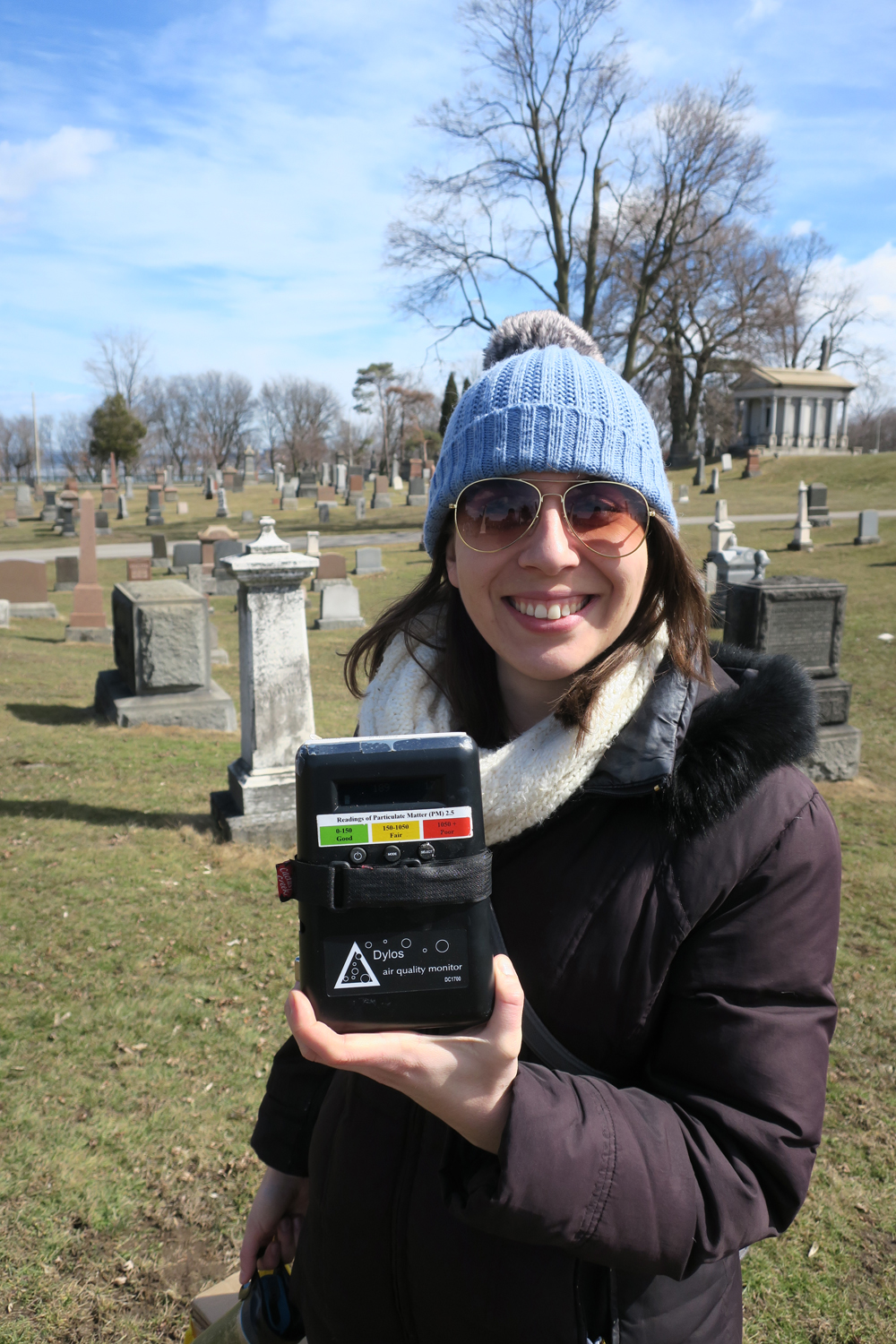

In 2018, the project surveyed trees in these six Hamilton neighbourhoods, ranking lichen presence and feeding the data into a map. Along with this low-tech method, volunteers also collected data using hand-held air-quality monitors that measure respirable particulate matter in the air. (Hamilton has the highest levels of respirable particulate matter of any urban centre in Ontario—a health hazard that contributes to cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses.)

This project is not just about monitoring air quality, though. It is also about galvanizing the public and the City to plant more trees in areas with high air pollution levels. Trees trap fine particulate pollution on the surface of leaves and needles, “effectively reducing human exposure by as much as 50 percent,” according to Environment Hamilton. “By drawing attention to the lichen and low air quality readings from technological monitors, we can encourage more focused tree planting in the neighbourhoods and bring this data to city decision makers.”

As Zanchetta puts it, “If we keep monitoring every year or so, it’s a good way to evaluate what’s going on.” And so our group huddles over tombstones, peering intently at the lichens fanning down from the rain’s drip lines created by carved letters, noting species and abundance, and possibly misidentifying some bird poop as a rare lichen find. Participating in this citizen science project, I’m feeling a bit “girl detective” (with a hand lens clutched tight to my face), a bit like a nerdy naturalist (such a strange spring outing!), and a lot like I’m immersed in Southern Ontario gothic—looking at lichen on a tombstone labelled simply “Baby 1876.”

TEXT BY LORRAINE JOHNSON, THE EDITOR OF GROUND AND THE AUTHOR OF BOOKS ON ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES.