Is Green Always Good?

An overgrown field under a Hydro corridor becomes a meadow and a community builder

TEXT BY LISA MACTAGGART, OALA

This story begins back in 2015 on a beautiful Friday afternoon of Thanksgiving weekend when Hydro One representatives hung notices on the door handles of 22 houses on a street just west of where I live, in Guelph. The notices announced that routine maintenance would be occurring the next week to clear “all non-compliant vegetation” under the powerlines in the open space behind these homes.

That open space is part of Silver Creek Park, a linear greenspace along the banks of the Speed River. The houses back onto the western end of the park where it widens out in a triangular-shaped land bump-out. This part of the park contains electrical transmission lines and pathways that connect two neighbourhoods to the river-edge trail system.

This was the start of what turned out to be a master class on how not to engage the public.

By Saturday morning, the Facebook group Save Our Forest had sprung into existence. As a member of the residents’ association executive, my inbox was flooded with cc’ed emails to and from ward councilors and on-call city staff. By Sunday afternoon, my Facebook page was exploding, and I learned how to turn off notifications. On Thanksgiving Monday, the funds had been raised to hire a lawyer to stop evil Hydro One. Tuesday afternoon’s paper had a headline about the clear-cutting of a beloved parkland forest. Local TV news stations came from Hamilton and Kitchener to do segments for the evening news. By that point, Hydro One had delayed the clearing in order to “work with city staff” and “consult with the public.”

Meanwhile, I was wondering, “What forest?” I live less than a kilometre from this park, but the area was not part of my daily routine. The few times each year that I strolled along those pathways, I had taken note of the impenetrable wall of buckthorn and the prevalence of garlic mustard. Far from feeling the restorative properties of nature, I found it infuriating that an invasive menace was spreading unchecked.

I can understand how this woody vegetation seems like a good thing to most people. The pathway is completely enclosed by vegetation, and homes are hidden from view. Even the neon sign on the Manor Strip Club across the river is not visible from the trail.

As a landscape architect, I found myself in an interesting position.

On the one hand, it was really exciting to see so many people shouting on social media and coming to meetings about saving a forest. On the other, it was sickening that the forest was merely a dense patch of buckthorn. So much energy and money expended for buckthorn under powerlines. Such a waste.

Removing that much buckthorn on Hydro One’s dime from open space adjacent to a riverine natural area is an opportunity to be seized. But when the city arborist said that very thing out loud, he was greeted with varying degrees of suspicion and accused of collusion.

After the initial shock and after the media went home, other voices started to pipe up. When approached to support the cause to save the forest, folks with GUFF (Guelph Urban Forest Friends), the retired director of the arboretum at the University of Guelph, and a project manager for the Nature Conservancy of Canada quietly stated that there was no forest to save.

Not my monkeys, not my circus—or was it?

I couldn’t shake the sense of obligation to speak up. I decided to offer my services as a landscape architect advisor to the Save Our Forest group but asked that they change their name. They are now called Silver Creek Park Community. I offered to work for one dollar.

Typically, as landscape architects we have a clearly defined role. But in this case, I wasn’t working for the owner of the land (City of Guelph) or the tenant (Hydro One). I was working for the residents who lived near the site. But my role as advisor, educator, communicator, and facilitator only worked because both city staff and Hydro One representatives trusted me and agreed that I could be helpful in this situation.

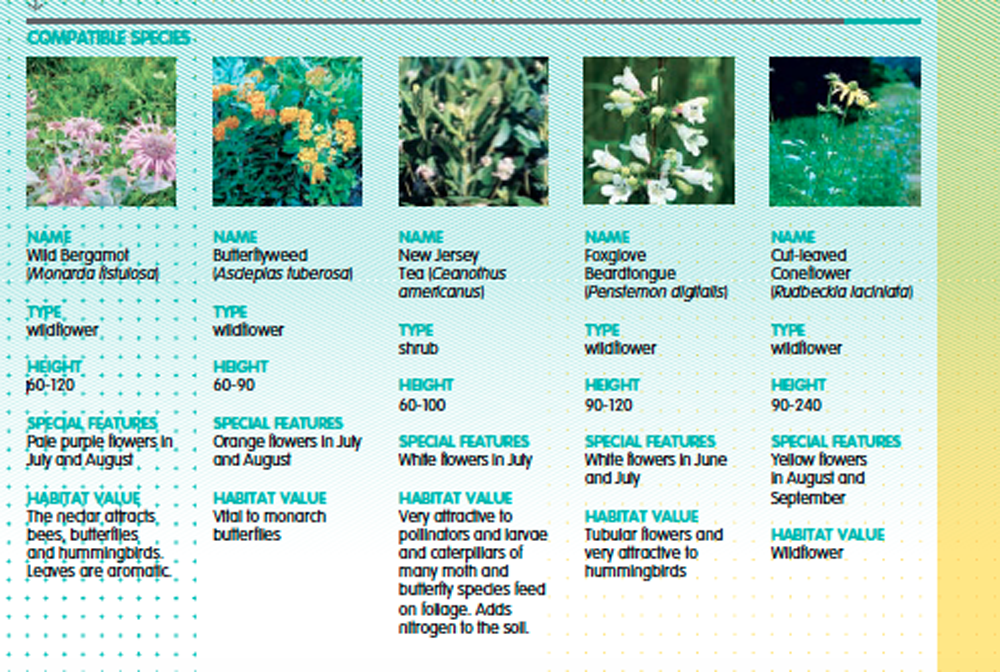

I mapped out a plan to build trust and share information through a series of community meetings. The first meeting was all about why there was no forest to save. None of my neighbours yelled at me. I came with images of restoration projects carried out by the Grand River Conservation Authority, to give an idea of what the space could look like. I talked about the fauna that could be supported by the meadow species in Hydro One’s standard seed mix. I tried to address the fears the neighbours had about a loss of privacy by showing them drawings of the relationship between their homes and the pathway. We discussed what a weed is, the important role of meadows in the ecosystem, and how dangerous buckthorn is for birds in urban areas. I invited all my fellow buckthorn haters to attend and provide back-up should it be needed. It wasn’t.

I shared my knowledge about what is permitted under Hydro lines and that there is a list of woody plants that can be planted, albeit at a higher cost than the proposed broadcast seeding. I shared my rolodex, and connected the not-for-profit group Trees for Guelph, led by James Taylor, FCSLA, with the neighbours.

Trees for Guelph works collaboratively with the City of Guelph and local schools to leverage volunteer energy to plant trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants in parks, school grounds, and private property. With Trees for Guelph on board, the residents and city staff were able to get Hydro One to agree to having a three-metre shrubby buffer of woody vegetation along the rear lot lines of the 22 neighbouring houses.

A relentless and effective negotiator from the neighbourhood, Jennifer Harrison, was able to get Hydro One to give Trees for Guelph a $10,000 beautification grant to pay for the plants in the buffer. The expertise from Trees for Guelph coordinator Moritz Sanio for restoration plantings led to some changes in the seed mix composition and helped convince people in the neighbourhood that a meadow might not be all that bad. Sanio and I provided lots of technical information about each species of pollinator that would benefit from the plantings.

And, a first for Trees for Guelph, some of the funds were used to purchase larger tree stock for the immediate neighbours to plant within their own back yards. The only condition was that the homeowner had to attend a planting demonstration by the Trees for Guelph coordinator to ensure that the tree was planted correctly. I helped homeowners select the type of tree they wanted and provided some guidance to get the trees planted far enough from the Hydro easement that the tree could develop a full canopy.

The balance of the grant was used to purchase 700 shrubs and 2,000 perennial plugs to plant within the three-metre shrubby buffer. In May 2016, more than 200 people showed up at Silver Creek Park in the pouring rain and planted every one of those shrubs and perennial plugs. And several members of the community hand-watered those plants for the next month during a June drought. The survival rate was incredible.

Prior to the planting date, I prepared a presentation, for the neighbourhood, in order to share what was going to be happening and to manage expectations. Meadow seed mixes take a long time to establish and this one in particular was being sown into a seed bank containing millions of buckthorn and garlic mustard seeds. We discussed how to protect the meadow from trampling by dogs and people as it was getting established. And lastly, we asked how the community would feel about removing the rest of the buckthorn from the park in areas that weren’t under the powerlines.

At the end of the day, I received an embarrassing number of public accolades from far and wide for the success of this project. Embarrassing because I didn’t make any of the financial or technical decisions or do much of the actual work to make any of it happen. I had no say in the content of the seed mix or the choice of the plant materials for the shrub buffer or any of the timing or resources.

Being able to see a bigger picture is what landscape architects do every day. I shared what I saw. I flexed my communication muscles—most particularly those in my ears. Building trust with people who are angry and fearful begins with listening.

I acted as a translator between the experts and the neighbourhood. I was a cheerleader—yes, we can dig 2,700 holes in whatever weather. I was the communication strategy planner so that a great number of people were empowered to contribute to success. They continue to do so. The park has a whole crew of garlic mustard pullers and meadow guardians who advocate that dogs remain on leash.

The meadow is flourishing. The City of Guelph is continuing to remove buckthorn from Silver Creek Park. Trees for Guelph has been planting trees in the areas outside the Hydro easements and is planning to reforest the areas nearer the river once the buckthorn is almost gone.

BIO/

LISA MACTAGGART, OALA, IS A GUELPH-BASED LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT. SHE CONTINUES TO REMOVE BUCKTHORN, GARLIC MUSTARD, AND PERIWINKLE FROM HER OWN GARDEN AS WELL AS ENCOURAGING HER NEIGHBOURS TO DO THE SAME.