A Once-in-a-Lifetime, Never-Before Place

Ontario Place was a declaration of optimism, and a visionary work of landscape architecture. When did we lose it, and how do we get it back?

TEXT BY ERIC KLAVER, OALA

“Architects of the world, we walk your streets and live in your towns, temporarily” – Nova Heart by the Spoons

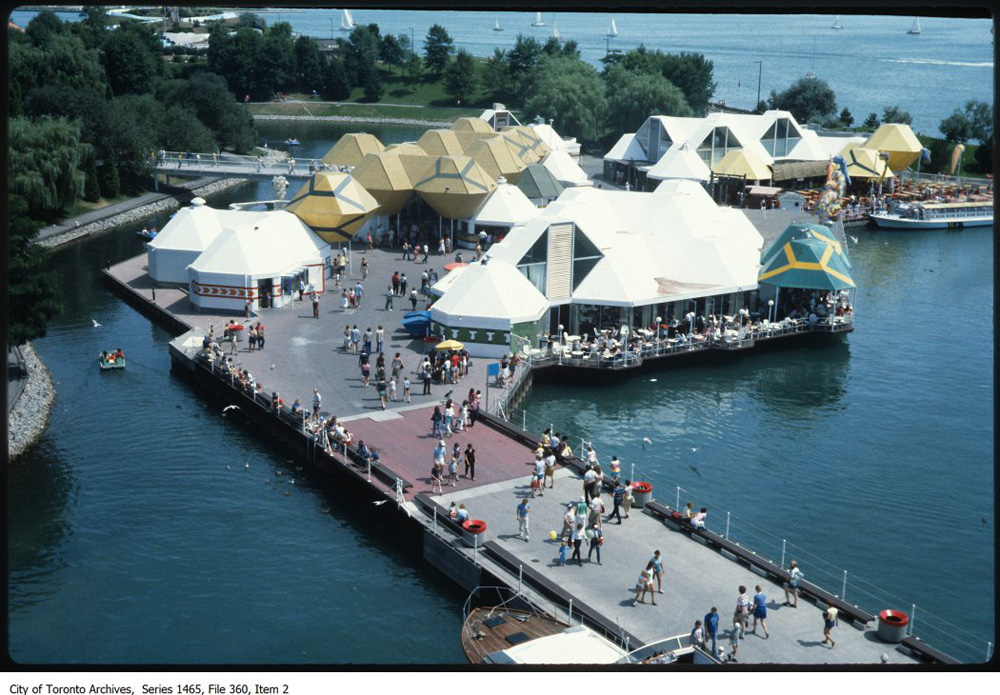

Riding high on the success of Expo ‘67, the Government of Ontario set out to develop its own, premier waterfront attraction, to promote all the province had to offer. Opened in 1971, Zeidler Architects (then Craig, Zeidler and Strong) with Hough Stansbury and Associates Landscape Architects, delivered a complex of ambitious, future-thinking architecture and, significantly, landscape that still resonates in the minds and memories of Ontarians today—the iconic pods on stilts, the legendary Forum, the first IMAX theatre in the “Bucky Ball” Cinesphere, the Children’s Village, and—unique for Toronto at the time—a waterfront promenade park, pivoting toward local ecology, with a view of the nascent modern Toronto.

My own experience, which I’m sure is shared by many, runs from childhood through parenthood: Children’s Village play, fueled by orange Tang from a Thermos (very space age); being thrilled, though slightly ill, while watching Silent Sky at the Cinesphere; warm summer nights at the Forum, feeling the lake breeze while doing the “safety dance” to Men Without Hats; presciently grooving to Nova Heart by The Spoons; watching birds fly from the lawn while hearing Aaron Neville sing Bird on the Wire; and then, yet again, running through the Children’s Village with my own boys.

Feeling its age, and perhaps the result of a few short-sighted decisions by management to compete with similar theme parks in the area, the government finally shuttered Ontario Place in 2011. A pale reflection of its former self, with empty pods, the Forum demolished and replaced by the Budweiser Stage, and the Cinesphere still operating as a repertory theatre, the current Ontario Government has seized the opportunity to redevelop the site, stumping for proposals to partner with a private developer to, in their words, “bring Ontario Place back to life as an exciting, year-round destination to attract local and international visitors. This could include sport and entertainment landmarks, public spaces and parks, recreational facilities, as well as retail.” Their website has all the aspiration of a real estate brochure, describing the site as “a unique waterfront asset, made up of 155 acres of land and water, and once served as an iconic cultural and tourism destination between 1971 and 2012.” That, and being “close to downtown Toronto and the Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport,” are highlighted as features that make it “an exciting urban renewal opportunity.” Breathtaking.

Notably, it fails to highlight the lead taken by Trillium Park, a significant return to the public legacy of the site that builds on its cultural importance and waterfront prominence.

More diplomatically, the OALA outlined their concerns in a letter by Past President Doris Chee, sent last February to Michael Tibollo, then minister of Tourism, Culture and Sport. Highlighting the many challenges the site currently finds itself in, the letter insists that “redevelopment of this dynamic waterfront showpiece must respect the ingenuity, cultural history, and values of the people of Ontario.” Of the many suggestions for improvement, the letter outlines the many assets of the site that should be incorporated and renewed: “the redevelopment should build upon the three constructed islands, with mature trees and rolling topography, the new Trillium Park and the William G. Davis Trail, and an environment that reflects Ontario’s diverse nature.” Perhaps most importantly, it recommends the government “build upon partnership and reconciliation with the Indigenous people of Ontario.”

The OALA is not alone in this sentiment, thankfully. In the interview that follows, I discuss with Ken Greenberg, planner and member of the advocacy group Ontario Place For All, for his thoughts on the state of Ontario Place, work that has been done since to renew the site, and the legacy of landscape architect Michael Hough, still on display there.

Eric Klaver: What are the attitudes, from a landscape or a planning perspective, that has allowed Ontario Place to decline, and what exactly is its current state?

Ken Greenberg: We were making a really good start at reviving Ontario Place. Trillium Park was a huge step in the right direction. The work of LANDinc and West 8 on that park demonstrates elegantly the potential of Ontario Place as a park. I’ve actually seen some concept plans that would have extended that kind of treatment from the eastern edge of Ontario place, where Trillium Park now sits, laminated against the edge, in what were formerly service areas, extending toward the center. Ideally, that would have produced a new kind of 21st century park, embracing both Ontario Place and Exhibition Place, which is absolutely needed, and could be the keystone of the return to the waterfront we’re seeing all across the northern edge of Lake Ontario and beyond. In terms of why it declined? When it was originally conceived in reaction to Expo ‘67 in Montreal, with the work of architect Eb Zeidler and landscape architect Michael Hough, it was an interesting and dynamic intervention. It spoke to a spirit of optimism, and was really conceived of as a park. But somewhere along the way we fell into a period of removing resources from public things and looking at them as assets to be monetized. A whole series of studies were done, mostly by accounting firms, looking at how to monetize this asset and stop spending public money. I think all of that was shortsighted and, even from an economic standpoint, made no sense. Very few of those studies actually looked at its great potential.

Among those, I did a study that I felt was trying to push in a different direction, looking at the opportunity for a merger of the two sites, around 2006. I worked with David Leinster of The Planning Partnership. We didn’t have a big budget, but we came up with an idea that had a lot of support, and we got very close. We’d been working with the administrations of the two sites. But ultimately the provincial government, for no rhyme nor reason, decided not to proceed. And so Ontario Place has languished, like many things if you don’t continually reinvest and keep up the grounds. Especially since a lot the things built when Ontario Place originally opened were almost temporary structures like you would find in an exhibition. The fact that they’ve lasted as well as they have is extraordinary, given the almost complete lack of maintenance. That said, if you go there now, you will see significant numbers of people are using it as a park.

And that should be its true vocation. From an investment standpoint, if all you cared about was the bottom line for the province or the city, and you looked at this as an economic asset, you would conclude, looking around the world at the value of great parks, that what they contribute to local economies is enormous. The lack of that park space would be a tremendous opportunity cost that we’d be passing up.

However, the Ford government seems determined to simply approach it as some kind of asset where the private sector would take over, and we’d get some version of a lifestyle center theme park. And although they’ve postponed releasing the results of the Request For Proposal, the conditions for the RFP would involve quite a bit of public money going into decontamination of the site and preparing it. But its proponents were not obliged to keep Trillium Park, they could simply provide seven and a half acres of green space somewhere on the site. They were not obliged to keep any of the artifacts—the Cinesphere, the pods, anything else—and the only thing that was required to be retained was the Budweiser stage.

EK: Which is probably the least interesting part of it.

KG: It was quite beautiful when it was the Forum.

EK: Oh yeah, I went to the Forum.

KG: And I think, on the landscape side, a lot of attention is being paid to the contribution of the Eb Zeidler and probably not enough to Michael Hough, and his vision for the site. The Forum was one of those pieces with the beautiful grassy slopes and naturalized landscapes, of which not much remains. In a sense, Trillium Park is homage to Michael Hough. But the direction the province seems to be taking is so unbelievably wrong-headed. Even if you are a fiscal conservative, it’s hard to fathom. Like so many things they’ve done, we’ll see if they are forced to backtrack. There’s a tremendous number of people who care about Ontario Place. Both in terms of personal memories, a sense of the site, but also a growing appreciation of the fact that having that site, plus Exhibition Place, as part of this emerging network of interconnected public green spaces is crucial, given our enormous population growth. The pressure on public space that we’re experiencing, the people’s desire to get to the water, and the design ideas have been around for a long time. They go back to that 2006-2007 study I worked on, but many people have been looking at really significant transformative ideas that would link the two sites, and extend the Martin Goodman Trail out around the water’s edge as it does in Trillium. That would provide better connections, and sequentially remove surface parking and create an integrated landscape within which there could be a whole variety of activities— ideally free, but some things could produce revenue to fund the programming, operation, and maintenance of the site.

EK: Talking about Ontario Place as a keystone, to me it’s always been in its own little isolated bubble on the shore. There’s a nostalgia aspect to that physical separation, but, in order to move forward, is it necessary to separate the nostalgia of Ontario Place from its idea, or can the two co-exist? Can they move forward and also connect to the city effectively?

KG: I would say all of the above. The opportunities for it to become more accessible are absolutely there. We’re getting all day GO service to Exhibition Place. We now have the 509 streetcar that comes from Union Station right to that GO station. Many people have come to the conclusion that there should be some kind of internal shuttle that would navigate the two sites (Exhibition Place and Ontario Place) from the GO station and the 509 streetcar. And I fear that the Ontario Line that the province is talking about is really tied to the idea of some mega commercial complex, but if there were, in addition to everything I mentioned, this Ontario Line (whatever form it takes), the transit accessibility would be far greater.

At the same time, we’re getting more and more cycling accessibility across the waterfront, the Bentway as an opportunity to connect right into Exhibition Place under Strachan Avenue, which is being planned now. On top of that, you have the huge amount of development occurring in the Fort York neighborhood, Liberty Village, Bathurst Quay, surrounding the sites on all sides. People can actually walk in, so its isolation can easily be overcome. All the surface parking is actually a tremendous asset that can be reduced and consolidated into some form of structured parking. All the conditions are in place to rescue it from its isolation, and the need to do so is obvious, in terms of the amenity it would provide.

But, having said that, I think the vision, the Michael Hough-Eb Zeidler-vision of this machine-in-the-garden, of the pods, the Cinesphere, a few of those objects… the garden has to be weeded, for sure. There’s a lot that can be taken out, simplified, made into a more permanent and beautiful form of landscape. A lot of the ways we think about landscape now in terms of environment—climate readiness, sustainability— are different how we thought then, and we could bring that new sensibility without making tabula rasa of the place, starting all over again, and losing its essential quality as a free and open public place.

EK: What would you keep and what would you get rid of?

KG: I would keep the Cinesphere, the pods, and some of the landforms that Hough conceived. I love the breakwater with the sunken lake freighters, out on the edge. But I think a lot of the smaller structures, the places where originally there were markets and cafes and things, could be upgraded. The uses are interesting, but they could be accommodated much better. A lot of the parking spaces—that whole band of parking on Lakeshore Boulevard— can be repurposed. The waterways can be improved, but the idea of a series of islands absolutely should be kept.

EK: What’s the biggest hurdle to renewal of Ontario Place?

KG: We were on the right track. Had we just continued with the recent start that Trillium Park had made, we could have moved toward an economically sustainable model that would still be a great public space. The biggest hurdle is the wrong-headedness of the provincial government, and this attitude of divesting itself of public places, of turning everything over to the private sector, washing its hands and saying ‘we don’t want to put any money into capital or operating, we want to run this as a business.’ At this point in time, in the evolution of the city, that’s counterproductive and economically foolish.

The only way I see that being stopped is if people push back, as they did on the waterfront before with the “no casino” movement, protesting the proposed MGM resort in Exhibition Place in 2013, and when the Ford brothers on city council tried to derail what’s happening in the Port Lands now with the Don River relocation. I’m hoping we can see a replay of that.

EK: You highlighted in an article that people are starting to come back to the park. There were 1.4 million visitors in 2018. A spark started with Trillium Park. As landscape architects and planners, how can we keep that agenda of public interest moving forward in the park?

KG: Well, the Toronto Society of Architects and the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario have stepped up on the built form side, and I would love to see the landscape profession step up equally, in tandem—I don’t think you can isolate one or the other—around the value of this as public space and its landscape legacy. And there’s a kind of wonderful sequence here from Michael Hough to the work that LANDinc and West 8 has done. Sometimes as design professionals, we’re all too willing to shrug our shoulders and do whatever the clients who pay want, and not take public positions. But this is a case where it would be great to have the landscape profession stand up and be counted.

EK: Who should be at the table, talking and engaging with Ontario Place and moving it forward?

KG: The hard thing is for the people, especially the younger people, who will miss this when it’s gone. Obviously, many of the people who have memories and experience with Ontario Place are stepping up from across the province. But it’s the future generations who will benefit the most from having a public, spirited, outward-reaching Toronto that places a high value on public spaces and landscape, versus an attitude that theme parks are good enough (which is the attitude of the current provincial government). But it’s hard to get that constituency. What was the line from Joni Mitchell? “You don’t know what you’ve got ‘till it’s gone?” I think that’s the situation we’re in, and we have to speak on behalf of those to come.

BIOS/ ERIC KLAVER, OALA, IS CHAIR OF THE GROUND EDITORIAL BOARD AND A PARTNER AT PLANT ARCHITECT INC.