Brampton’s 20-Minute Walkable Neighbourhood

A Q&A with Yvonne Yeung

Text by Kaari Kitawi, OALA

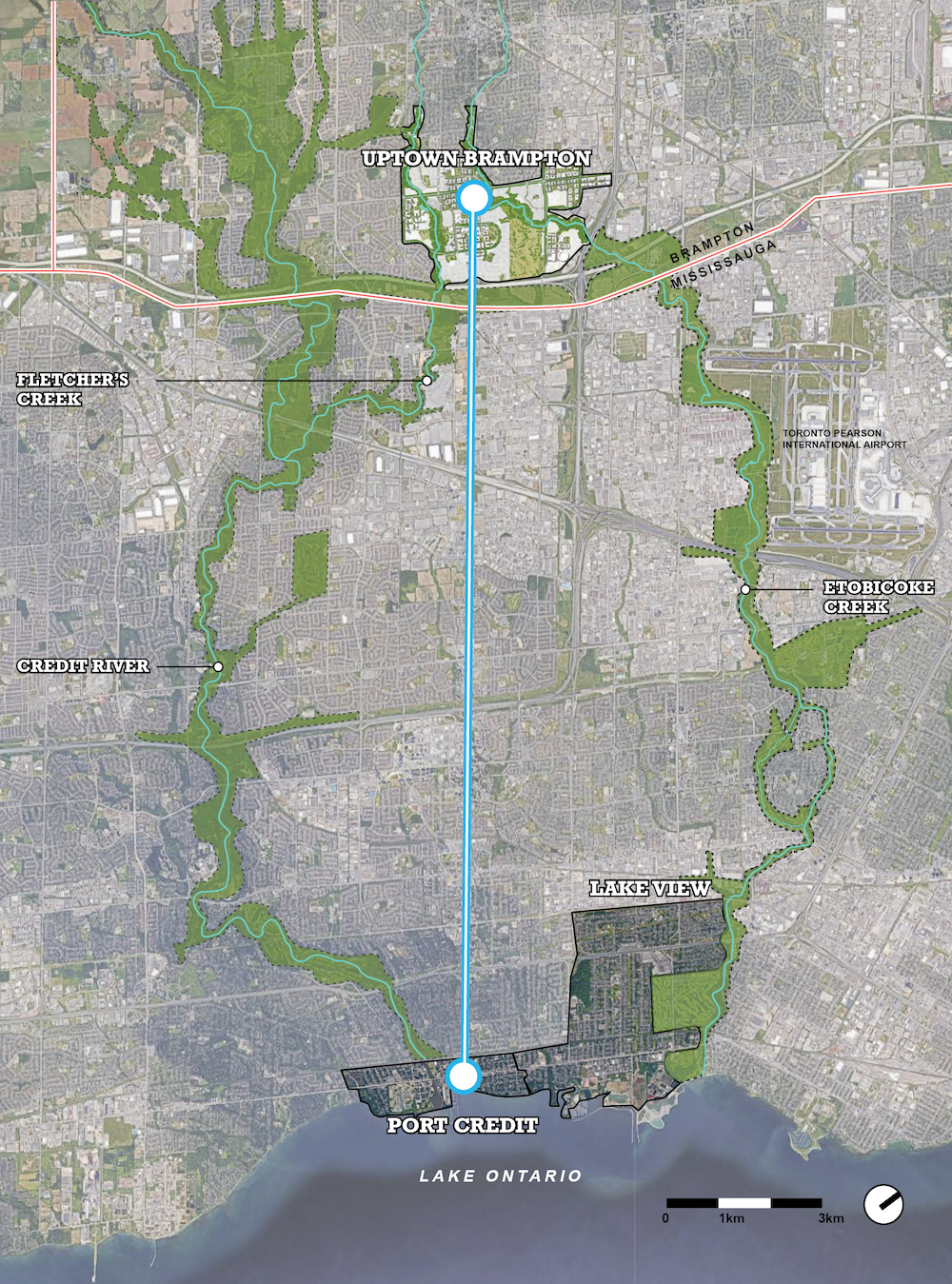

The suburban City of Brampton, Ontario, is the ninth largest city in Canada, and growing fast. Like many cities in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, Brampton is looking to reimagine itself, and prepare for the future. In 2018, it adopted the Brampton 2040 Vision, which aspires to promote sustainable and healthy growth, create five Town Centres, build complete neighbourhoods, and integrate a number of mobility options, including regional transit hubs, into the design.

In keeping with the 2040 Vision, Brampton is transforming it’s Uptown into a 20-minute, walkable neighbourhood, with an “Urban Community Hub.” To explain the plan, and the city’s ongoing transformation, we spoke to Brampton’s manager of urban design, Yvonne Yeung.

Kaari Kitawi: Recently, you organized a virtual workshop conducted by the City of Brampton, in partnership with Urban Land Institute Toronto (ULI), the University of Toronto’s School of Cities, and the City of Helsinki. Is the City of Brampton using Helsinki as a benchmark, and will the collaboration continue?

Yvonne Yeung: This was an initiative I started with Urban Land Institute, prior to joining the City of Brampton. The idea was surrounding the delivery of walkable communities within urban growth centres, served by rapid transit. The “Getting to Transit Oriented Communities Initiative” was a great team effort among various thought-leaders within ULI, including Ken Greenberg, who shared in this vision. As part of the visioning of this initiative, I tapped into my experience in the private and public sector, and travels to Europe over the past two decades. I am particularly intrigued by the Scandinavian model of creating family-oriented neighbourhoods that integrate nature and social hubs at the heart of communities. I had also attended a conference in Denmark and seen the need for collaboration and exchange of design ideas at a global scale.

When the provincial government issued a directive on establishing Transit Oriented Communities, a group of ULI leaders began to look at the overall transit infrastructure to identify how to strategically position cities that are undergoing suburban transformation, including Brampton. We selected Helsinki as an international benchmark, because they had succeeded in shifting their city planning policies from being car-centric to transit-oriented, and created walkable neighbourhoods. Brampton sees an opportunity to do the same by prioritizing public health and environmental sustainability.

When establishing the walkable neighbourhood, Helsinki’s city planners seek to elevate the happiness of their citizens by ensuring the community facilities are in place from the very beginning.

KK: When Waterfront Toronto was redeveloping the lakefront, the parks and the public realm were put in place first and the buildings later. Is that what you mean by community facilities being in place at the beginning?

YY: Yes, the Urban Community Hub is a critical component in building communities, and making this facility available to the first generation of residents is important to the success of creating a walkable neighbourhood.

KK: When you say Urban Community Hub, what do you mean?

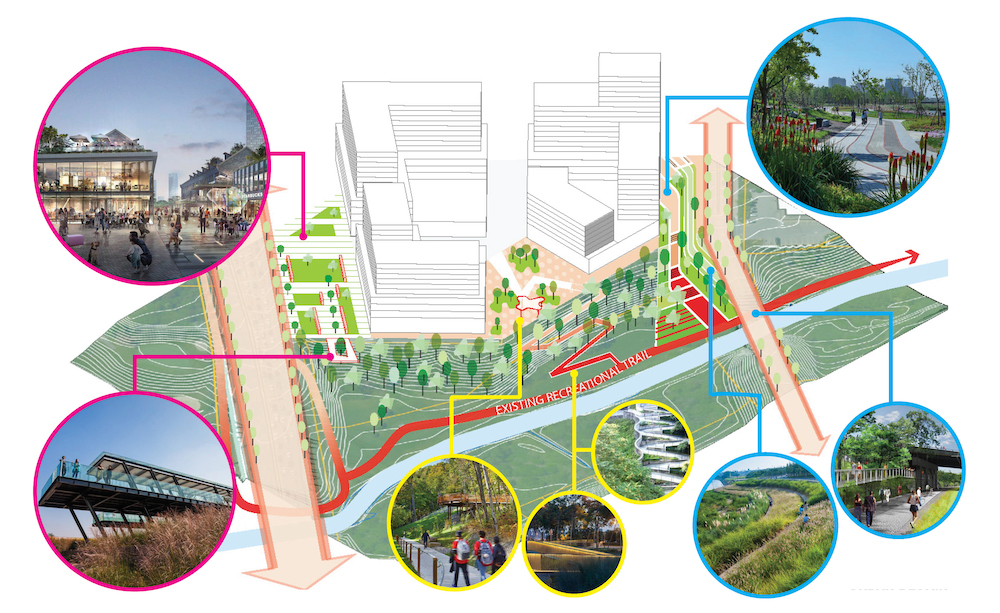

YY: The Urban Community Hub is a multi-use facility prototype we developed under the direction of city council. It was developed in collaboration with the library board, school boards, Peel Region Public Health, and Peel Social Services. The hub is designed as a “pavilion in park,” with a daycare, school, library, recreation centre, exhibition and performance spaces, technology and innovation space, and it will integrate green technologies with learning gardening.

Drawing from the lessons of the Helsinki model, we are establishing this prototype as a campus at the heart of the neighbourhood.

We have a unique opportunity, with the rapid transit investment that is happening very fast, the decentralization of economic activity that has been accelerated by COVID, with people working from home, and the request for office spaces across the region. Walkable complete neighbourhoods connected to transit nodes are the most ideal places to live and work.

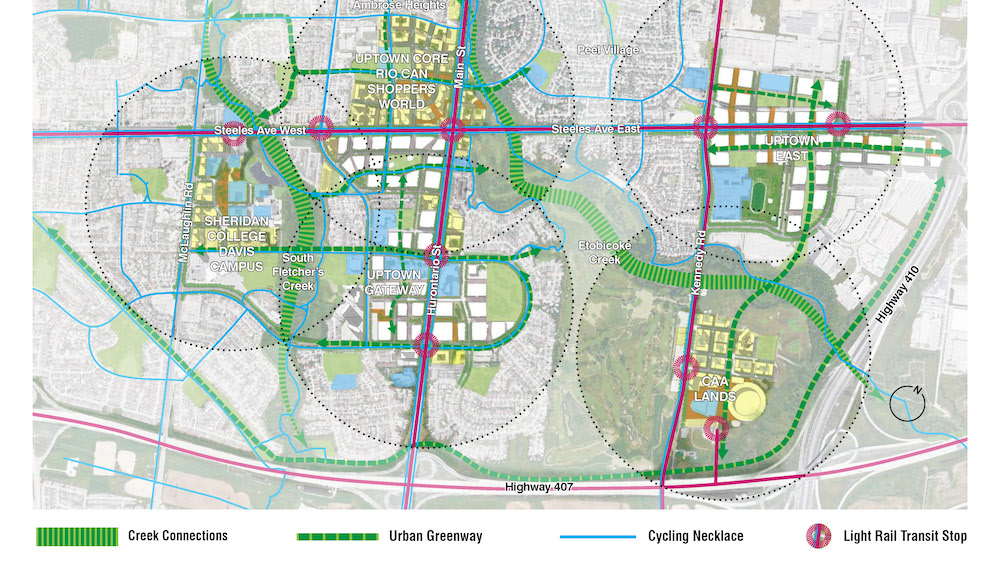

The Major Transit Station Area envisions complete walkable neighbourhoods will be created within 800 metres from all the rapid transit stops. A majority of the trips will be made by walking, cycling, and riding transit. As designers, we have to align with these planning policies and see how to create a condition that can benefit both public sector and private sector.

At Uptown Brampton—Hurontario Street and Steeles Avenue—we are working with seven developers. The urban vision is to create 14 million square feet of new, high-density, mixed-use development. The projected population at this transit node is 100,000. We realize, to achieve best outcomes, master planning at multiple scales, not by piecemeal design, is key.

The City of Brampton sees an opportunity to increase competitiveness by repositioning education to build talent and cultivate an innovation economy. We are looking to diversify our portfolio to become an “Innovation Corridor,” by aligning to the Kitchener-Waterloo corridor and attract more technology jobs.

At Uptown, we are also removing the need for car ownership and replacing expansive parking lots with high-quality public spaces. To achieve this, we are working closely with transit, transportation planning, and other departments to design the transit around this campus, so there is seamless connectivity. The bike trail will be improved so that children can bike to school safely, negating the need for drop-off.

We are also interpreting the advice of Peel Region Public Health into tangible design projects to encourage an active lifestyle and minimize the spread of infectious diseases. The public spaces at the heart of the community will be interconnected for the enjoyment and safety of residents. These spaces will provide additional benefits of improving cognitive performance and mental health.

KK: Was the workshop initiated by the City of Brampton or ULI?

YY: It was an invitation-only workshop, using the ULI platform. We invited 200 people, including representative from Sweden, Helsinki, Netherlands, local developers, and professionals. The intent was to get independent feedback from professionals without a vested interest in the project.

KK: Some of the 905-area municipalities don’t have a catalyst such as the waterfront. How do you see Brampton creating a catalyst to attract people to live here?

YY: The Urban Community Hub is envisioned as a catalyst for development. It will be at the heart of the development, surrounded by the community. It will be connected to great public spaces, schools, parks, trails, and the valley system. Green streets will be integrated, and Vision Zero will be implemented, to reduce pedestrian fatalities at the intersection.

When Oslo was rebuilding after the war, their efforts were led by the mayor, an engineer, a doctor, and a designer. In my opinion, that must have informed their focus on building walkable neighbourhoods, connected by efficient transit. They have a collection of 15-minute walkable complete neighbourhoods that are connected by the public realm as the glue. We are exploring applying this same thinking to Brampton and using the Urban Greenway as our glue.

KK: You mentioned the important role quality architecture plays in the Scandinavian model, are mid-rises the preferred built form for Uptown Brampton?

YY: We don’t see tall towers on two or three storey podiums creating the neighbourhood environment that fosters community. To facilitate the design judgement, we go through rigorous, logical explanation demonstrating the importance of the public realm in driving the development. Across the region, designers are trying to avoid building vertical suburbs. The built form needs to create the right enclosure with the surrounding street and block. It also needs to provide comprehensive, family-sized dwellings that provide lots of eyes on the street.

Public space is the key driver to achieving the vision. As designers, we have to take the driver’s seat and provide clear vision to influence the shaping of the physical city. I have seen this demonstrated very well in Arabianranta, in Helsinki. The developments are primarily driven by public art, which is placed throughout the public realm and acts as wayfinding.

At times, designers focus their energy on getting a perfect plan from 10,000 feet above, instead of designing from the ground at the human scale.

KK: How does the proposed plan compare with Cornell in Markham, are there any similarities? You are familiar with both developments.

YY: As a resident of Cornell, I can share my view. This new-urbanism community was developed 20 years ago, and it’s an absolute masterpiece. It has fine-grain design, with a collection of interconnected public parks and open spaces. This feature makes it easy for children to navigate their way to school, without needing to cross the street. The homes are designed for people to be able to have home businesses, with ground floors easily converting into office or retail space. The layouts also allow for eyes on the street and foster a strong sense of community.

KK: How has COVID impacted the Uptown Brampton plans, are you tweaking it?

YY: COVID has shed light on the need to prioritize public health and social equity, and increased the daytime population in neighbourhoods with people now working from home. Families have learned to share space in the house and be flexible. Working parents—particularly those with young children—are structuring their workday to meet family needs and work obligations. Employers, too, have had to be flexible to accommodate staff.

The active transportation and new daytime population will act as a catalyst to create a safe neighbourhood and foster social cohesion. With many people working from home, it is a perfect environment for starting small businesses and boosting local economy.

The proposed Community Hub is envisioned to be operational 24 hours. We are testing the idea of having shareable retail spaces on the ground floor. Instead of having fixed, long-term leases, the space can be let out on the short term to start-ups, to use space as and when needed.

The spaces will be designed to support residents through different life stages. The neighbourhood will be a learning ground for children throughout their development. Programs such as internships, performance spaces and urban agriculture will be integrated to enrich the overall education experience.

The federal government is providing further support through community innovation grants. This will create opportunity for the community to partner with non-profit and or municipality to retrofit some of these public spaces.

KK: You mentioned that time was an important piece in all this. Is that the reason testing is critical to get buy in?

YY: The CityPlace community in Toronto that we celebrate took years to come into being. When I was at university, it had a centralized park with a temporary outdoor golfing area. The public spaces were installed first, then the high-density neighbourhood. The community would have benefited if the recently completed school would have been done at the beginning. We are learning that there is opportunity to attract families by prioritizing the early delivery of community infrastructures. The “20-minute walkable neighbourhood with community hub,” provides a scalable model to unlock an urban growth centre by building community, and it can be replicated across the region.

BIO/ Kaari Kitawi, OALA, is an Urban Designer at the City of Toronto and is a Ground Editorial Board Member. She a graduate of the Masters of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Toronto and has a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics from Kenya. Prior to moving to Canada, Kaari ran her own landscape firm for over 10 years.