Something in the Dough

Text by Victoria Taylor, OALA

The heard and unheard voices that inspire and guide us through the built practice of landscape architecture are diverse, each one providing critical insights into the site analysis, design, and construction phases of our work. How do we activate new paths toward inclusive design when existing maps are limited? For inspiration and insights, I invited Thevishka Kanishkan and Rayna Syed, co-founders of newly launched activist design group Common Space Coalition (CSC), and artist Sameer Farooq, to talk about Sameer’s recently installed public artwork, a tandoor (clay oven) and semi-permanent fixture commissioned through In Residence, an artist-in-residence series at the Scarborough Museum curated by Aisle 4. The In Residence program is meant to challenge the role of a colonial museum in present-day Scarborough, Toronto. The following is an excerpt from our conversation in December, 2020.

Victoria Taylor: Hello Sameer, Thevishka and Rayna. First, I want to acknowledge the important and engaging work you all are doing. I’m hugely inspired. Let’s start with introductions.

Rayna Syed: Thevishka and I are recent MLA grads and, since graduation, we have been looking for ways to continue our thesis work around context-specific design and encourage systemic change in our industry. We launched CSC this past summer after writing a letter to our professional bodies in reaction to the lack of response in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd. It was signed by over 100 of our colleagues across Canada and asked that our leaders acknowledge their complicity and complacency in the role landscape architecture plays in defining who belongs in a space. The CSC came into fruition as a steering committee to continue to lobby our governing bodies on accountability, and to create a community conversation on how best to move forward. The CSC asks, “How can we write a new framework that is participatory and rooted in community engagement from the beginning and create equal spaces for everybody?” We believe that by pushing this conversation forward, we can begin to challenge our unconscious biases and, in a generation from now, we will see systemic change.

Theviskha Kanishkan: Our approach is through activism and research and to focus on incorporating community voices, marginalized voices, community leaders, and activists directly into landscape architecture to result in more economically, socially, and ecologically resilient designs.

Sameer Farooq: This is really incredible to hear! I come from a typography and graphic design background—before I became a full time visual artist—and I understand so much the bristling against official bodies and how we shape shift as practitioners to accept the rules, the different exams, the requirements, and content and how we have to embody the history of design that can be so different from our own lived histories.

TK: Reflecting on what we have read about your work in Scarborough, Sameer, we believe in the importance of responding directly to cultural context and community in our design work. Something like a tandoor oven, placed in an extremely diverse community with a diverse range of socio-economic backgrounds can happen in our work by rethinking diversity on our design teams, our steering committees, and in our working groups. We believe that context-sensitive landscape architecture is possible if we revisit how we currently practice. If we have committees that directly represent the communities we design for, we will have stronger, more resilient designs because the design actually engages the community.

VT: Sameer, would you like to introduce your work, your approach to this particular tandoor project, and your process?

SF: Sure. What I’m understanding is that we want to dig into process and the different ways that one can cultivate a more informed community engagement to result in the final work. My process was a bit weird. When I got asked (by curator, Aisle 4) to do a site-specific work, I really struggled at first with what I wanted to do. Around the same time, I went on a trip to Pakistan with my dad and, during that trip, something just clicked. In all of these cities where I traveled (Lahore, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar, and Karachi) tandoor ovens were vital meeting places for people. So the starting point for my research method was very diasporic. When I started to research in Scarborough, and research what populations use tandoor ovens, they were all present in the Bendale neighbourhood—from South Asians to Uyghurs, they all use a tandoor. So an oven could be a very direct way to engage in a sensory and familiar feeling of home.

Much of my process is informed by my background in anthropology and the anthropological methodology of participant observations, interviews, playing with the value of the insider, versus the outsider role, participating in things directly, or just sitting in places for long periods and watching.

RS: Your anthropological methodology insight ties closely to a few notions that have been percolating recently. This action of sitting and watching and seeing how people really interact seems to have fallen out of the landscape architecture process, and instead there tends to be an understood, universal approach to how people act and the generic requirements—seating, a dog run, utilities, plants—that we embed into our designs. We can’t assume that we know how all types of people inhabit space. Especially, as designers, if diversity is lacking in the office or from developers, we minimize diverse opportunities and ways of life. This process of daily observation, of how a diverse range of people move in space is missing. As landscape architects, post-occupancy evaluations after the first year (or three or five years) is something we need to consider bringing back to our process.

SF: Yes, I think so much about this divide: between looking through assumptions, or by seeing what is in front of our eyes. When you look at what’s actually in front of you, and you spend a lot of time in a park, you take in many different pattern languages. For me, when I saw the spontaneous family gatherings around a charcoal barbecue, I said to myself, “Let’s build a big one that people can book and use.” While some communities can really benefit from a massive splash pad, others just don’t have fun that way.

VT: Even though the tandoor project has not been realized, and there has not been a proper launch the way that you and the curators envisioned, there is still so much we can learn through this process of research and making.

SF: Because of COVID, we weren’t able to have a real launch, but what we imagine is that the oven will become an important meeting spot during cultural events, or when different things happen in the park. We did several test fires, and we also had some interesting experiences with the Museum’s kitchen. It’s amazing seeing these brown and Black people dressed in full Victorian garb, making butter tarts and pies, and then, for us, they started making naan dough for the oven; everyone was sharing different naan recipes and we began experimenting.

RS: There is so much to this idea of community artists and leaders and new activities happening in these colonial institutions, and how the process of responding to a context can be ongoing and evolving to continually respond to people’s needs. At the end of the day, landscape architecture is driven by money and development, and we have to respond to that. But that’s why we find your project so interesting: because it brings these ideals of responding directly to community context into the built environment and into a design detail that gives back to the community.

SF: I’ve thought a lot about landscape architecture in terms of what we look at in the material itself, looking at where it comes from and what are the political ramifications of that material. But here in my practice, the material is dough. It’s incredible because it’s economical, nourishing, sensory, highly available, very transportable—they could easily engage this colonial kitchen and it suddenly became a bakery in Pakistan. I love the potential of landscape architecture to be seen as an expanded field, and it’s so exciting to look at the materials and the possibilities of what you can use to engage the public on land. This is definitely about dough.

TK: As you are talking, Sameer, I’m seeing how the tandoor dough is the material and also the program element—a detail of your design that activates and decolonizes the museum’s kitchen, re-centering the colonial history of the site to bring in new stories and new cultures to reframe the history of this cabin. De-centering all of that is something your dough is doing. It’s pretty wild to think about.

SF: Yes, I couldn’t believe the museum was game for it. They were very open. They gave us a beautiful spot on the lawn for a semi-permanent structure that the museum will manage. We will see how it all unfolds once people start meeting again, and it does already perform this function as a beacon for people to gather around. There are a lot of good feelings around this process.

VT: How did the community interviews you did affect your tandoor design?

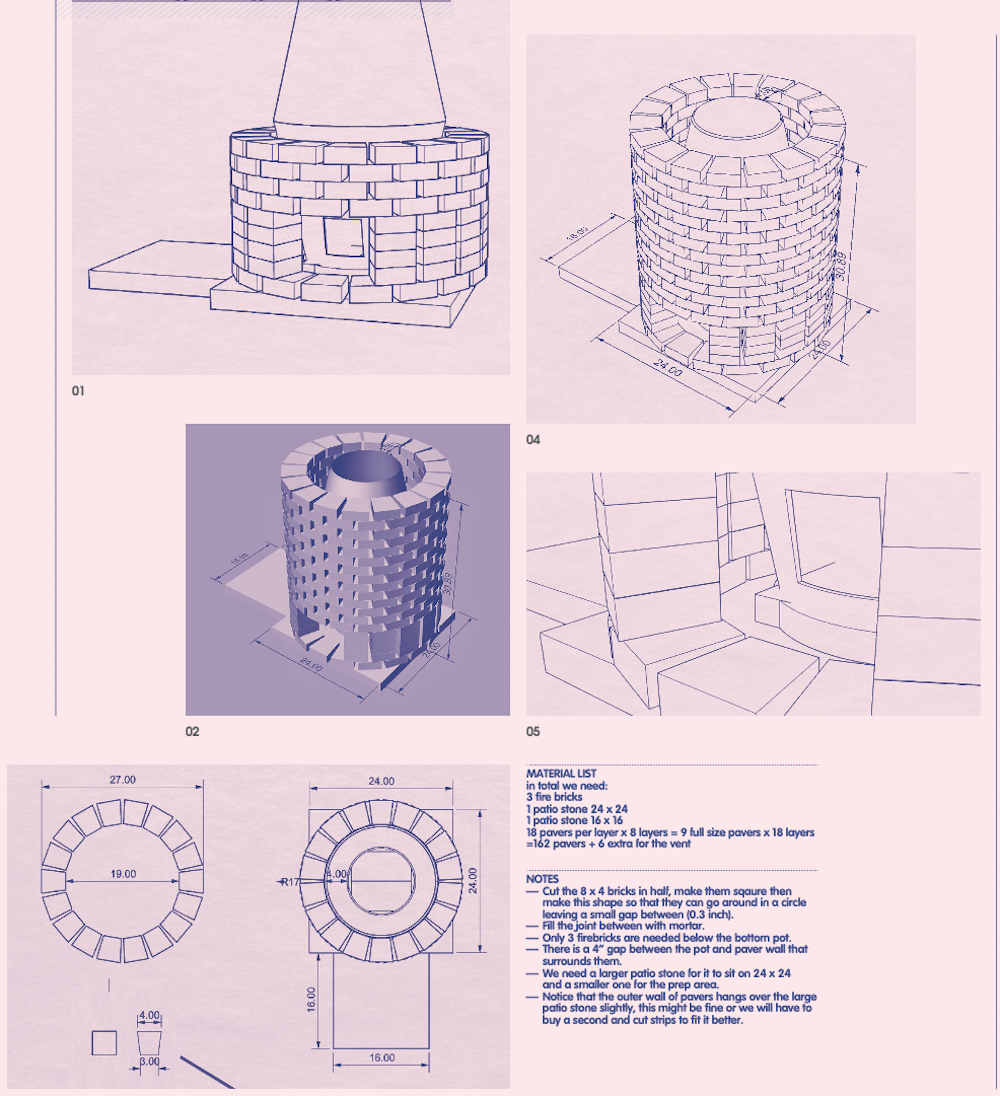

SF: The curators visited local restaurants to ask about how they used their ovens. But a lot of them were electric. We did speak to a couple of tandoor walas in the wider community; one was a tandoor export business in Oakville. I did some general research for various designs and calibrated that with what was available locally and within the budget we were granted. If I were to do it again, and inspired by these conversations, I can imagine the whole community building a super tandoor. It did have the foundations of community advice—how things need to be insulated, coal versus wood, and bringing in these types of conversations—but the design was determined by me, and for this first try it was very much based on what was available in the time frame.

RS: When we think critically about art and community initiatives and how to activate these into our practices, it can be a lot easier, on some level, for smaller practices. For larger design firms that pitch to more capitalist-driven clients, it’s hard to begin the rewiring of clients’ brains so they realize that this is an important thing to do. Certainly, one of the most challenging things for us is how do we, as young designers starting out, restructure the profession. But as emerging professionals with a critical eye, we understand that if we were really going to decolonize ourselves and our unconscious biases and the inherent hierarchies that surround almost every single profession, the vital first step would be to step back, unlearn, and to amplify the voices of people who are doing this work already.

VT: Public art is often a way to have these types of critical conversations. Can the public art process be a way to activate

the changes we are talking about here?

SF: I do see my piece as public art, and definitely see these collaborations are vital because we (artists) don’t have all of the skills to conceive of a project with all of the protocols that need to happen in public space. I was surprised this one happened so easily. I love thinking about the value of bringing in outside voices into one’s practice, of bringing in people who aren’t accustomed to the day-to-day habits of a certain profession, and can point out blind spots in the process that maybe aren’t a good fit. There are interesting openings where the engaged landscape architect and the artist can become a team to amplify each other’s voices, work through the red tape, and have a certain amount of distance to question things and offer new insights. It is a wonderful way to give both parties a valuable opportunity, bringing two very different skill sets together in order to navigate the fortress that has been set up to allocate land and use land in certain ways.

VT: Any final thoughts?

SF: This has been wonderful because the project happened and then and we didn’t have a launch, so it’s been really nice to reflect on it through all of your eyes and to think back a year and consider what it was.

BIOS/

Victoria Taylor, OALA, is principal/founder of VTLA Studio, and co-founder of ====\\DeRAIL Platform for Art + Architecture, a curatorial experiment to animate public spaces along linear landscapes. vtla.ca // derailart.com

Sameer Farooq is a Canadian artist of Pakistani and Ugandan Indian descent. His interdisciplinary practice investigates tactics of representation. With exhibitions at institutions around the world. Farooq received several awards from The Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council, Toronto Arts Council, and the Europe Media Fund, as well the President’s Scholarship at the Rhode Island School of Design. Reviews and essays dedicated to his work have been included in Canadian Art, The Washington Post, BBC Culture, Hyperallergic, Artnet, The Huffington Post, C Magazine, and others. He was longlisted for the Sobey Art Award in 2018. www.sameerfarooq.com

Common Space Coalition is a coalition of landscape architects across Canada whose goal is to combat racism in our professional practice. We seek to engage in a professional, positive, and transparent relationship with our professional bodies (CSLA, OALA, BCSLA, AALA, and others) as an arms-length advocacy group/steering committee. www.commonspacecoalition.com

Aisle 4 is a Toronto-based curatorial project that initiates and promotes socially engaged artwork. Through collaborations with artists from a range of disciplines, they present critical public art experiences that reach beyond core arts audiences to animate unsuspecting spaces and connect communities. www.aisle4.ca/in-residence

Thomson Memorial Park is a midsized public park located on Brimley Road in the Bendale neighbourhood, located east of Toronto, Ontario. It is the site of the Scarborough Historical Museum and includes historical houses of the founding family of the former City of Scarborough, the Thomson’s, from the 1790s. Scarborough Museum consists of four buildings that were moved to the site between 1962 and 1974. These include: Cornell House, a clapboard, Scarborough vernacular-style farmhouse; the McCowan Log House, restored to its 1850s appearance; Kennedy Gallery, a small former farm outbuilding; and the Hough Carriage Works, which houses a collection of artisans tools donated by the Hough family who operated the original shop at Hough’s Corners.