Rising: Black, Indigenous, women of colour expressing healing, history, and experience through landscape

Moderated by Saira Abdulrehman

BIOS/

Cheyenne Thomas is an Anishinaabe designer from Peguis and Sagkeeng First Nations. She has a Bachelor of Environmental Design and Architecture from the University of Manitoba. After graduating, she worked at an engineering firm, before moving to projects. She has presented overseas and across Canada. One of her biggest projects is as a facilitator and designer for the Indigenous Gardens at the $75-million transformation at Assiniboine Park in Winnipeg, Manitoba. She also a member of the board of directors for The Forks North Portage.

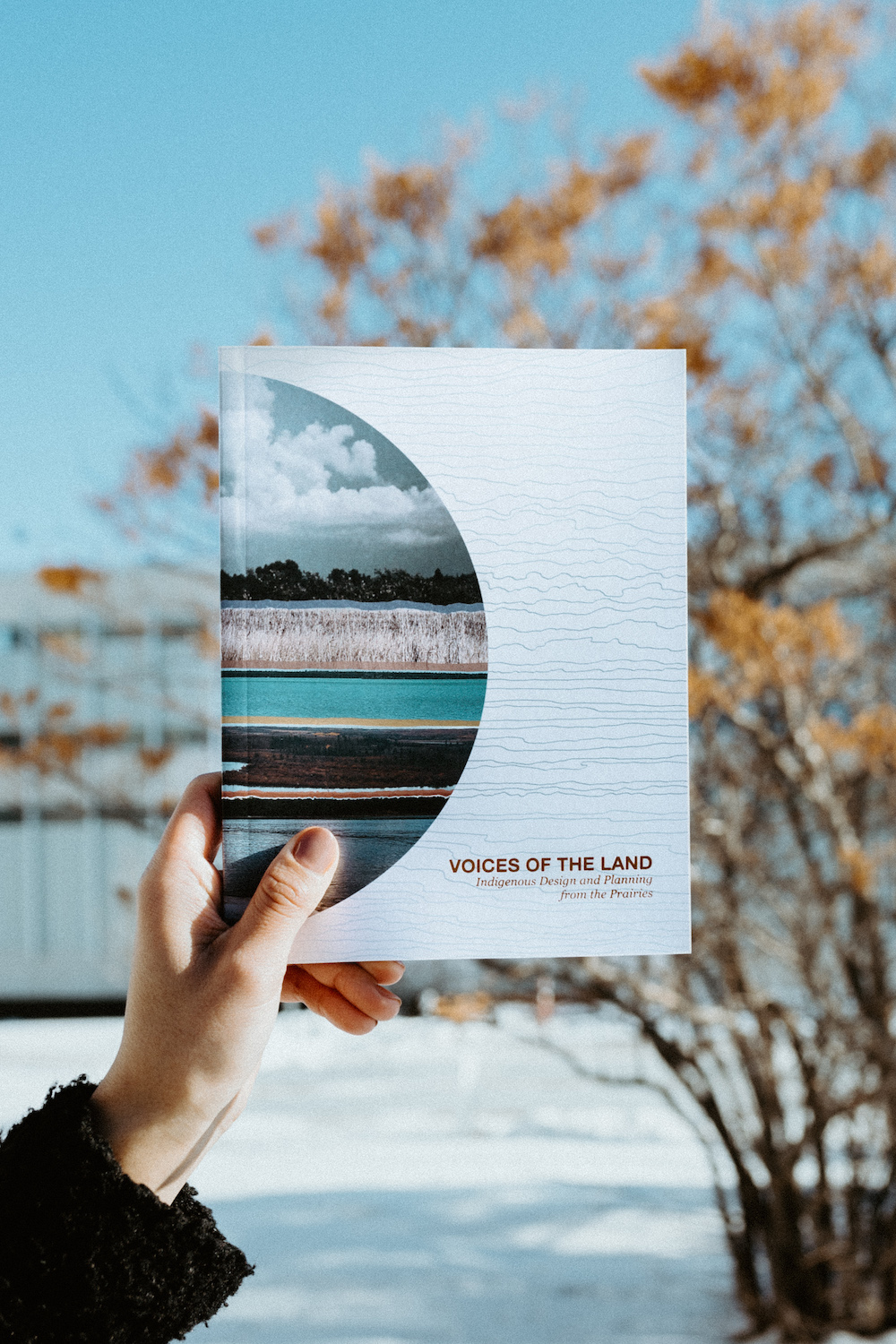

Reanna Merasty (Cree, Barren Lands First Nation) is the Co-Founder of the Indigenous Design and Planning Student Association at the University of Manitoba (UofM), advocating for representation and inclusion in design education, and the Co-Editor of the publication Voices of the Land: Indigenous Design and Planning from the Prairies. Reanna is a MArch Candidate at the UofM, and an Architectural Intern, focusing on reciprocity and land-based pedagogy. Follow @um.idpsa on Instagram

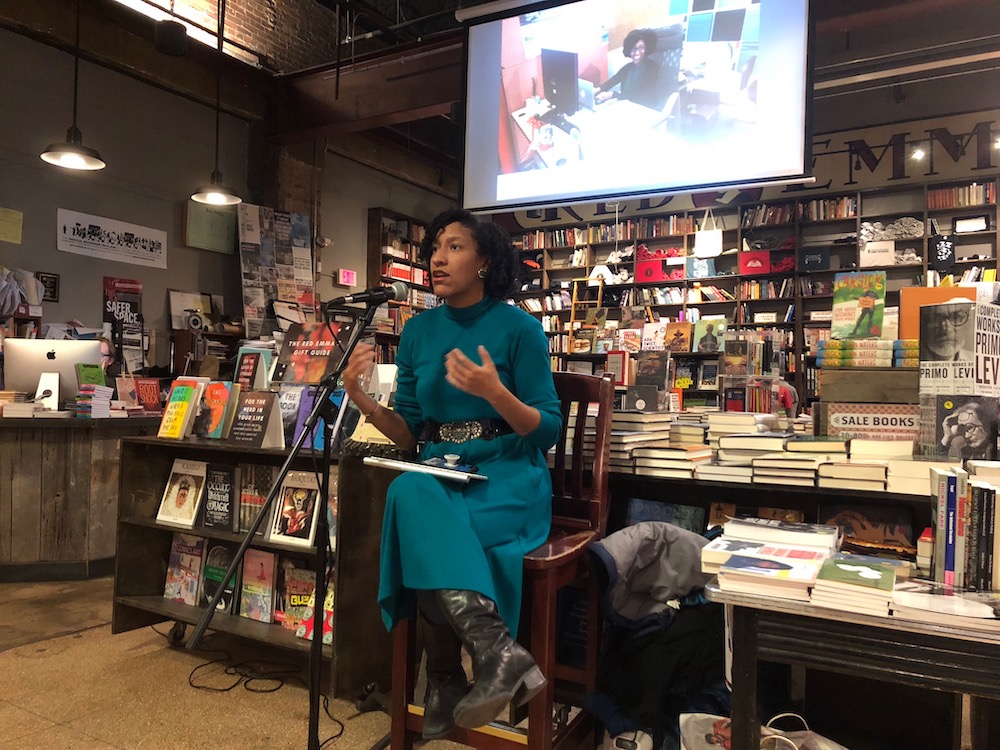

Kristen Jeffers was one of the first people to bring the concept of Black urbanism to the internet and social media in 2010 by purchasing and launching The Black Urbanist, which in its 11th year continues to be a resource for Black urbanism at the intersection of feminism and queer/trans life. She is the author of the forthcoming A Black Urbanist Journey, a memoir/manifesto for Black queer feminist urbanism. She is the creator of the K. Jeffers Index for Black Queer Feminist Urbanism, a guide, measure and data centre to assess the thrivance of black queer feminist urbanist people globally and curator of the Black Queer Feminist Urbanist Book Cannon and School. Finally, under the banner of Kristpattern, she shares her own journey into sustainable fashion and invites others to do the same. A sought-after public speaker and workshop leader, she makes her home just outside of Washington, DC and never has her hometown of Greensboro, NC far out of her mind.

Saira Abdulrehman is an experienced urban designer working between Toronto Canada and London, U.K. (were she is a chartered landscape architect) since 2015. She is one of the founders and principal designers at The [204] Design Collective, a POC and women led design studio that challenges and explores inequality in the built environment, amplifies the voices of marginalized communities, and explores alternative forms of practicing Architecture, working towards establishing a more accessible and diverse profession. She is a member of the Landscape Institute’s Diversity and Inclusion board, the Urbanistas London, and the Editorial Board for Ground Magazine at the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects.

Saira Abdulrehman: I want to begin with a story that got my mind turning on this topic and interested to have this conversation. I’m sure you guys know Beyoncé’s sister, Solange Knowles—who I love and always say is my favorite architect. In 2016, she wrote an article in response to harassment she and her family faced at a concert in New Orleans. She was standing up and dancing with her family and there were people in the crowd throwing objects, jeering, and telling them to sit down. It led her to write an article called “And Do You Belong? I Do.” She writes, “The biggest payback… was dancing right in front of them with my hair swinging from left to right. My beautiful black son and husband, and our dear friend Rasheed, jamming the hell out with the rhythm our ancestors blessed upon us saying… We belong. We belong. We belong. We built this.”

I begin with this because I think Solange does a beautiful job of applying the concept of joy, wellness, and healing to her work. She uses dance, fashion, makeup, music, architecture, and community performance, and puts it all into her art, leading with confidence, femininity, and joy. That really evokes a strong healing energy in her work (I think that’s what makes her such a good architect). So, I’d like us to talk about how we might begin merging healing and wellness, and/or prioritizing feelings of love and joy within our professional practice.

Cheyenne Thomas: With the Assiniboine Park project in Winnipeg, they gave the park that huge renovation, $75 million, and they wanted to have Indigenous gardens as part of it. So they handed that aspect of the project over to me and my father and HTFC Planning & Design landscape firm, and we were the lead designers of that process. We wanted to bring in community members, youth, elders from all different communities and hold intimate gatherings and share a space with everyone in an intimate way of getting ideas, concepts of our people, and our teachings. That lasted about six months, so we gathered all this knowledge and developed principles about how our people used to lead, and values that we hold within our culture—dancing, music, the drum—and we use those principles to embed that into the design of the park. There are very specific nodes, led by those principles and concepts, that are embedded in the park now to be healing, in a way, for our people—to heal the land, and the relationship between non-Indigenous and Indigenous people.

Reanna Merasty: Every part of my creativity, artwork, or design comes back to myself. And what really changed or shifted when I was in school was the idea of reconciling and restoring relations with myself. That included my confidence in being brown, being Indigenous, being Cree, and understanding what all of that meant, and how I could tie it all in to what I’m creating. In the first three years of my undergrad, I didn’t want to be myself. I was restricted, and completely overwhelmed. But once I started to understand my feelings of love and those joys that your culture brings and what that offers you, it changed how I saw design and everything else. Everything that I created was an extension of myself.

SA: Reconciling with self is so important because, institutionally, our fields, schools, and the workforce doesn’t always look like the four of us. So it’s difficult to not lose yourself in the process of becoming a professional in these fields. And realizing self confidence and connection to our identities actually makes us better designers. What has been the general reception of this kind of work when you bring the concept of leading with joy and healing when you’re approaching a project?

CT: In my personal experience, it’s refreshing. A lot of times our projects seem so confined and restricted. But the Assiniboine Park is what my and my dad’s work is all about. And because he’s my father, we have a certain kind of bond when we’re working on projects, and firms or employers see that, and it’s different than the typical colleague-work dynamic. The park, when we’re working through it, is all based on beautiful teachings of healing through ceremony, and love and patience. Even the fact that it took four years to do just gives space for genuine emotion, and when people see our work now it’s finally materializing, these spheres that I’ve designed like the women’s node are all carved in cedar, which is healing in our culture. When we present now to different people, showing the actual pieces, we’ve never seen anything like this before.

Kristen Jeffers: I’m glad to hear you all talking about healing, because it’s so necessary. We burn ourselves out quickly. This is my 11th year of doing this as a formal work and it’s been up and down. Years ago, when I started The Black Urbanist, I could count on my hands how many people were okay with using the word “Black” in a professional setting, and people of the African diaspora that actually accepted and affirmed their own Blackness, professionally. When I first started, I would not wear my hair like this, it would be straight. If it wasn’t straight it would be perceived a certain way. It’s evolved over time. At first, people were not sure what I was doing, and thought it was mostly an academic thing.

In my last monthly newsletter, I called out a lot of people who have used, especially last year, the current awareness of social justice issues—Black Lives Matter, or Landback, or the #solidarity hashtag—saying, ‘I went to this march, we hired someone new, we have had this task force, we had a meeting, I’ve read this book.’ Well, what are you doing if there are grievances in your office? If there are people you’re only listening to because you like them or their message is more palatable, have you really done the work? I know some of my acceptance right now is genuine acceptance. I’ve heard that when I start talking about healing amongst women of colour. That part it brings me joy, because that’s what I want. We want our communities to thrive. We get into this because we’ve seen disparities. I mean, I was seeing my father walk six lane roads with no sidewalks. My mom talks about how, in her classrooms, some children’s parents didn’t want her to teach, well after Brown vs. The Board of Education supposedly integrated all of us (which did not happen).

I would say, as a whole, the media world gets it. In the design world, it depends on how willing to be outside of the mainstream folks are. It’s the same, internally, with fellow Black women, queer people, folks of colour, or other marginalized folks: it depends on their relationship and their process of decolonizing, looking towards liberation, looking towards their own self care and self determination. Otherwise, it’s still kind of an up and down, it varies by group. I would say it’s up to a 50/50 balance of not getting it and really getting it.

Because of that 50 per cent, I have at least enough energy to take it to 51, to keep going with the work because I know the approach is needed. It took time for us to get where we are today, where there are disparities and needs to unpack and decolonize, and we have a ways to go. Sometimes that journey has to start within ourselves and we have to build a foundation for ourselves before we can look back.

RM: In terms of academic faculties, my work has been well received. But there’s still a long way to go in terms of institutions and colonial structures that are within it. For our association, that’s partially the reason I stayed there for my masters: to change it, to use my voice, to speak up and develop it more for people like me that could go through architecture and design. We really started to use our voice to speak about misrepresentation, or lack of representation. And we’re getting into the realm of curriculum development. Everyone is willing to learn and wants to play a part in the process, but, because there’s so few of us in this field, it can get overwhelming. People are willing to learn, but I don’t think they realize how much weight it is on us, as BIPOC people, to be advocating for all of this work, speaking up and using our voice. It puts a lot of weight on us as individuals, and I don’t think they realize that. In this process, it shouldn’t just come from us, it should come from everybody. Everyone should see this lack of representation, or be able to see what’s lacking in our spaces and institutions.

KJ: What this work has asked me to do is to make sure I’m not saying I speak for everyone. When people are outside looking in, when our plights hit the media or are presented at academic or professional organization conferences, or we are contracted to be this resource, we’re supposed to put ourselves in a box. But that’s not always our place. It’s a space of healing to say “no.” It’s a space of healing—even though you may benefit financially—to say “this person is actually better for this, this is what that person does. This person has more of the regional experience, or lived experience,” or “this person that you’re rallying behind, they have a community already.”

I started deliberately shifting the focus of my work towards inter-community healing. I was left on the proverbial side of a road because I wasn’t going the direction that our movements, or at least our professional places, were going. So what was I going to do? I had to look at where we are, at what other people are doing, and examine myself to see if I’ve been going with paradigms that don’t work for me. It’s been two or three years since I started that process of re-examining my work, and it’s been rewarding me because I know that it’s coming from a better place and I have more energy to get out there and do it.

I also want to tell people to continue to reach out to more voices. Yeah, there are several of us who we’ve heard from a lot, who people like hearing from. We all have great things to say. But continue to reach out to all of us. Examine all of our work and our backgrounds and think about our journeys. Especially since this is about public space. We’re creating public space. Each protest movement or mobilization has not affected everyone equally. Anybody who is reading this and trying to be involved, know your limits, know your boundaries, get to know, on a local level, what’s needed, and then find that exact place where you fit in. Don’t feel like you have to do it all, don’t feel like you have to stand up in front of people and be somebody you’re not, or represent everyone, because that’s the quickest way to burn out.

SA: What do we think or anticipate the future of our cities look like? How do you see us moving forward, when we’re talking about leading with community and healing? Do you see our spaces being shaped in a different way at all?

KJ: When I get asked the future of cities question, they always want me to have an overarching, global answer. I want to really zoom in on our specific ethnic communities and our regionalisms and be able to modify architecture, urbanism, planning, or whatever it is, because there are nuances. My hope for the future of cities is that we look inward. Specifically, those of us in communities of colour. We solidify ourselves, our villages, and our cities inside of the major metros, and then we evaluate the questions that the regions we live in are asking of us.

For me, being involved and active where I live is why I’m able to speak for so many places. The challenge for us is to dig in and not necessarily think because somebody else is doing something we can do it—while still keeping it in mind. My hope is we really work on solutions individually, as well as collectively.

SA: I appreciate that because oftentimes, as people of colour, we’re asked questions and people expect this utopic solution: how are we going to solve inequality in public spaces, period? What are the main steps towards that? That doesn’t leave space for nuanced conversations, or to explore what that actually might look like in our respective communities. We still need the space to do that, and we weren’t afforded that space.

Reanna you were talking about how you decided to stay at the University of Manitoba for your masters degree, because you felt like there was more you could change internally by staying. How do you see that future unfolding for you and your organization?

RM: I am very optimistic in this, but I still think it has a long way to go. I was reflecting this past year, because I’m about to leave and I’ve been working on this for about two years: how could you maximize the retention and reach out to more Indigenous youth to come into the idea of architecture design and planning. But then I think about the amount of Indigenous students right now. We were able to have about 16 Indigenous students in our entire faculty, which is probably the most in all of Canada. We will be part of the built environment, we’re building up our cities, we’re building up our architecture, design, our landscape. When I think about that, I feel very optimistic. But the one thing, in terms of the faculty or the design community as a whole, is to still think about the broader community. That, although we have all these voices and perspectives, we can’t speak for everybody, like Kristen says. We can’t speak for other members of the community that are not within post-secondary education, but still have community knowledge, are very knowledgeable and have their own strength, who are doing important work for our houseless relatives, and our northern relatives.

We think we know everything but we don’t. We don’t have all the answers. Those come from those lived experiences that we should be able to use in order to build our cities up. We’re not superior just because we’re in post-secondary. We’re not superior, with these degrees, over other members of the community. I want to emphasize that we’re just as equal as someone who is homeless in inner-city Winnipeg, we’re on the same level as someone working on community initiatives in the north end. Those voices should be raised up in order to build our cities and communities up. That’s what I want to emphasize, in terms of our public spaces and how we create our own environment.

SA: Nothing can really replace lived experience, right? When we’re charged with designing the public realm, we don’t know everything. Architect Iddris Sandu says architects are the most empathetic people in the world because they design spaces for everybody except for themselves. And I want that to be true, but I don’t actually think that’s the case at all. There’s the ego of the architect and the designer who thinks they have the capability of stepping in anybody’s shoes and designing for them and that’s just not true. Maybe that’s part of healing too: realizing we don’t actually have all the answers, realizing that we’re not the face of the community and stepping back and letting other people take up space.

Thanks to Saira Abdulrehman for coordinating this round table.