Healing: Virtual landscapes

As landscape architects, we are deeply in-tune with the fundamental principle that being in nature has a restorative effect on our health. Healing gardens have been in existence since the Middle Ages and continue to be associated with hospitals and care facilities. However, understanding of the psychological effects of nature were advanced only relatively recently; in large part by the work of Rachel and Stephen Kaplan in the field of environmental psychology during the 1970s, to the 1990s. Their work on Attention Restoration Theory had a profound impact on how landscape architects design parks and gardens.

In 2016, the World Health Organization released a report concluding that increased exposure to green landscapes in urban areas is associated with a reduction in mortality rates, improved mental and physical health, and fewer birth complications. As such, it is clear why immersion in nature is an important aspect of health and care programs, globally.

By contrast, we are also deeply aware that access to nature is not equitable. Racially segregated communities and lower-income areas often encounter significant physical, social, and structural barriers to quality green spaces. Additionally, there are those who may be housebound or mobility-constrained who simply cannot access nature.

Starting in the 1990s, there has been an increased interest in utilizing virtual technology to connect people who cannot access nature and its healing effects. Virtual Reality (VR) has been at the centre of a number of clinical studies in the prevention and treatment of mental and psychological health problems. The practice of connecting patients with nature through VR has been studied in the treatment of chronic pain management; in patients undergoing cancer treatment; as therapies for mental health, focused on anxiety disorders, eating disorders, phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder; and cognitive rehabilitation. While many of these studies have shown levels of success in VR-immersive natural environments as a treatment therapy, there is still not enough evidence to definitively draw correlations.

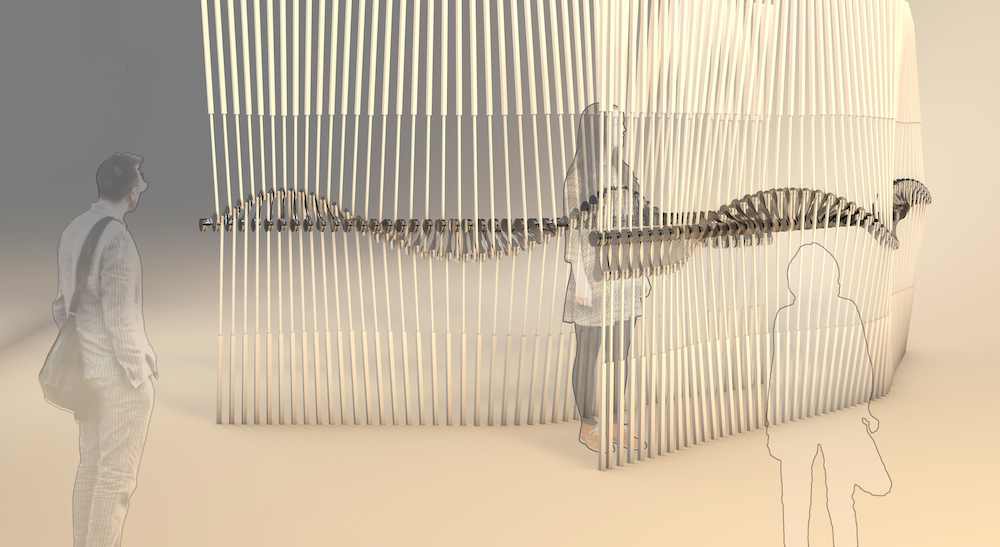

Another approach to using interactive technologies in unlocking the restorative effects of nature is through physical, movement-based sculptural art. Fellow Ground editorial board member Dalia Todary-Michael has been studying this very idea through the process of building an artistic body of work using linear and radial automated machines that work on interactive feedback loops to replicate lively and nuanced movements in nature. Her work “In Rhythmic Fragments,” in collaboration with Saria Ghaziri, uses two interwoven waves that respond to the collective rhythm of people moving in its environment, captured by an infrared camera, shifting their interaction from asynchronous or synchronous to simulate harmony or dissonance. The effect of this and her other installations is to draw-out memories of nature: to make the viewer recount and relive the experience of watching wind pass through trees, or the steady and repetitive motion of waves on a beach. The outcome brings forward that individual’s memory and amplifies their cognitive recollection through heightened contemplation, back to that experience, to re-engage with the therapeutic effects, individually and collectively. Dalia is continuing her research to better understand all the possibilities of nature-based, interactive technology in the arts, and how to bridge them in landscape design to heighten well-being and leverage more pronounced experiences of stimuli from nature and, ultimately, enhance our connections to the landscape.

As animals, humans need to connect with nature. It revitalizes, heals, and calms us. With the explosion of urban environments and their continued intensification, nature is becoming less accessible to us. On the other hand, technological advancement is constantly evolving, and, with it, we seem to be bridging the gap to nature and reconnecting with the land—hopefully leading to a greater respect for what nature we have left.

Text by Mark Hillmer, OALA, member of the Ground Editorial Board and a landscape architect working for a multi-disciplinary design firm in Toronto.