Landscape and the Smart City

Text by Alison Lumby, OALA, Jennifer Sisson, OALA, AND Max Li, OALA

What do we mean by “Smart?”

The “Smart City” evolution is on. All around us, we are seeing the use of data-based technology expanding and affecting many distinct aspects of our daily lives. Smart technologies are influencing how we move around, shop, socialize, and get informed. It is also changing the way the environments in which we live are responding and adapting to pressures of modern life, climate and natural phenomena, and to us. As these smart technologies becomes more prevalent, as a profession, we believe there is a need to consider the role that the practice of landscape architecture, and us as landscape architects, have in the use of smart technologies, and how the Smart City may influence our profession.

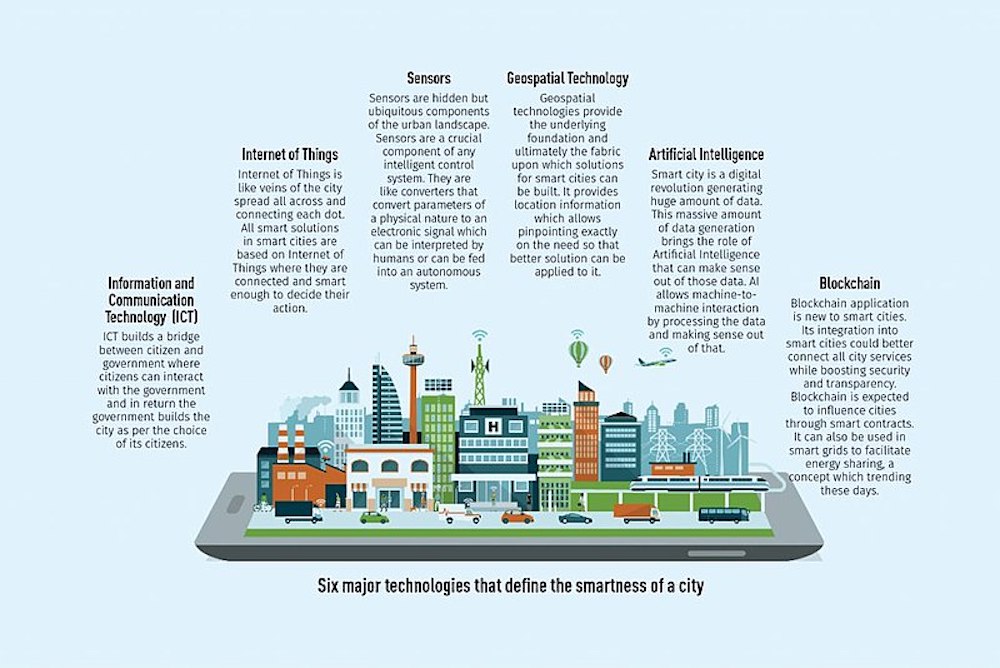

There is no one, hard and fast definition of a Smart City, however the basic principle is that a smart city is one that is enabled by a framework, or network, of connected information and communications technologies—the Internet of Things (IoT). Providing real-time collection, transmission, and analysis of data, the intent of smart technologies is to enrich user experience, better monitor, anticipate, and manage operations, improve quality of services, ease sharing of information, and enhance quality of life.

Furthermore, the aspiration is that data-enabled infrastructure will make cities more responsive, resilient, and better able to predict and adapt to what are becoming more and more frequent climate-related events. The Smart City would be an enabler of net-zero emissions and the framework towards net-positive (fewer emissions). Yet, when we look about us today, the technological advances are, for most part, near invisible. While we may see the proliferation of smart bus shelters, data hubs, and waste bins, for example, the influence of the Smart City on the fabric and form of the built environment and the way we go about planning, designing, and building may not be as immediately felt.

Being proactive in guiding and implementing Smart features

So, why should landscape architects be engaging with smart cities? Where is our place in in a digital and data-based world? Can we opt out and say “no” to further adoption and reliance on data-based technology?

Data and technology are not inherently good or bad: they are tools that can be applied in multitude of ways, and to the benefit of society and natural systems. Through this lens, smart technologies, and the possibilities they enable, are an evolving component of our social-urban-ecological system—a smart infrastructure ecosystem. The Smart City could be an integral layer of urban infrastructure that makes lives better and improves the quality of the environment. It need not be showy. In fact, in the vein of the iceberg analogy, 90 per cent of smart technology may not be visible, what we see and experience being the outcomes of the system. For example, one significant cause of waste in urban water systems is over-usage, and data-based technologies can not only help monitor and alert us to real-time issues such as leaks and blockages, they can analyze and help adapt the system to allocate and deliver only the quantity of water needed.

There is great potential for smart infrastructure to support more resilient, nature-based systems, and to augment socially conscious, biophilic design approaches. However, while data and data analytics (including AI) can be powerful tools, they are not problem-solvers. We are. As design professionals, stewards of the natural environment, and drivers of people-centered, community engaged placemaking, we have a role in wielding smart technologies and digital integration for the betterment of health, wellbeing, social equity, and environmental resiliency. From a technical perspective, it is not our intent that landscape architects must become experts in smart technologies, but there is a role for us in the ability to deliberate on and discuss smart solutions, to be able to advise our clients, advocate for opportunities that are in the public best interest, enable better care for natural systems, and to challenge those that are not.

It is worth noting that the term Smart City implies this is an urban phenomenon, but our rural and remote communities have as much at stake in the smart cities debate, as does the management and care of many of our natural and protected places.

Smart ethics

A healthy dose of wariness is no bad thing; there are some major ethical questions that need to be addressed. Some of these issues revolve around how data is collected, and by whom. What personal data is being collected, who owns the data, who has access to it, who decides how it will be used? What about our right to privacy and ability to opt-out? Who is responsible for oversight, when considering the scale of data collection and level of automation involved? What about data security risks and breaches? What are the fail-safes? Might this enable or conceal new or existing systemic forms of discrimination, or be discriminatory in and of itself to those who are not connected into the framework? Are we risking over-reliance on data? What about unanticipated consequences we are simply unable to foresee?

When we look out at the complex, often ethically contentious nature of smart technologies, landscape architects—whether as advocates, advising caution, or opposing smart cities—should be a proactive part of the conversation.

As a profession, we can advocate and influence data governance. We can challenge the collection of personal data. We can support inclusive systems such as those that require minimal user input, do not gather or rely on personal information, and where input is required it is intuitive and basic, using platforms accessible to a broad audience.

Using Smart tech for good city-building

With all the risks, why might landscape architects find themselves advocating for smart solutions? Because of the potential to better stewards of the environment, and to improve people’s lives. The conversation is often focused on people and personal smart devices, however there are numerous, non-personal means of gathering data already regularly utilized, both about people and their interaction with the city, as well as natural systems and the impacts of changing environmental conditions, such as footfall and user counts, tides, temperature and rainfall, air quality, and light and noise levels, to name a few. We are already implementing solutions such as AI-enabled irrigation to improve the sustainability of our projects. We already use data to inform our design responses.

The smart industry has generally focussed on five key technologies: smart energy, transportation, data and devices, infrastructure, and mobility across different smart systems. As landscape architects, we are engaged in all of these aspects to a greater or lesser scale. If we focus specifically on some of the ways landscape architects are engaging in smart cities to benefit people and environment, and changing the way we approach design, we can look at examples such as:

Energy efficiency: from the choice of a light bulb, to integration of systems that actively monitor and report energy usage back to consumers and utilities, smart sensors and other data tech enable more informed personal and project decisions, better grid management, and diversified, distributed energy production.

Smart infrastructure: sensor technologies can help municipalities optimize efficiency and manage municipal assets in more sustainable, adaptive ways. For example, sensors installed at stormwater management facilities, such as bioswales, may be used to monitor and provide real-time data on performance of these features for water quality and the reduction of burden on storm sewers, as well as analyze and predict trends in storm events. Data-based analysis can also serve to improve service quality and operational efficiencies. For instance, park maintenance may be informed by factors, such as footfall and use pattern data.

Smart parks: the integration of smart technologies into our public spaces can allow another level of engagement in spaces, and attract wider audiences. Solar-powered infrastructure, such

as benches offering free wifi and charging stations in a socially inclusive setting, for example. Digital platforms can augment built spaces, allowing users to explore public spaces remotely and learn about real-time conditions and amenities, including barrier-free facilities, in planning visits—which can help overcome barriers to equitable use.

Smart trails and wayfinding: smart technologies offer another means of supporting active modes of moving ourselves around our cities, promoting healthy lifestyles and social inclusion by making it easier, more accessible, and more enjoyable to get out and explore on foot, bike, and while using mobility aids. Online or digital technologies can be used to augment fixed signage. This can range from interactive digital displays to integration of QR codes that link to online content.

Performance metrics: landscape performance is the qualitative analysis and measurement of the impact of landscape design on the physical environment. An example of this is in the development of Winston Churchill Meadows Park, where 1,500 new trees will absorb up to 72 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, supply enough oxygen for 3,000 people, and provide as much potential cooling effect as 15,000 room-size air conditioners operating 20 hours per day. Sensors can collect data on a range of factors, from air quality to visitor counts, and help evaluate the efficacy of programming and capital expenditures. The data collected by smart technologies can be used to inform design standards, support business cases for capital and revenue investment, and help convey the benefits our profession brings to the design of spaces at all scales in a relatable manner.

The key theme underpinning the examples above is all the implementations involved collection of non-personal sources of data to provide significant advances and benefits. It is through such projects that we see a potential, significant benefit to our profession through smart technologies and infrastructure systems.

Perhaps it is time to champion a new stream of smart: Smart Design. For us, this would address both the process of design, integral with a smart approach to socially conscious, biophilic design principles. There is room for the integration of data-tech into the creation of adaptive places, and this flows through the early stages of planning, to design, implementation, and the monitoring and ongoing adaption of spaces.

From the outset, we can ask how to utilise smart technologies to provide a more equitable design platform for society and nature. At the planning and preliminary design stage, this means looking at the data layers of the city as part of our site analysis, augmenting physical assessment and engagement with correlations that data can reveal to macro- and micro-scale influences on the space. This may consider data relating to demographics, climate and environment, transportation, user numbers, real estate, user enjoyment, and can draw from a wide range of data sources.

The Smart opportunity

Recognizing that Smart City technologies are all around us and transforming the fabric of urban spaces, as a profession, we need to continue engaging in the discussion, staying informed of the benefits, challenges and risks, and being open, if cautiously, to embracing data-tech in our design process and projects. We should prepare to work closely with our clients, decision makers, and the public as ambassadors for socially conscious and environmentally responsible smart cities. Through our work, we are in a position to ask the critical question of ‘who does this serve’ and thoughtfully reflect and weigh the potential benefits and drawbacks of implementing these technologies across a wide range of purposes and places. Our profession can contribute to guiding inclusive, smart cities around the world that benefit the public, while minimizing the associated and potential risks.

BIO/ Alison Lumby, OALA, AALA, APALA, SALA, CSLA, CMLI, has been delivering integrated landscape and urban design solutions for over 18 years. As Design Lead for WSP’s Landscape Architecture and Urban Design practice Alison works to advance performance based ecological site initiatives, contextual site programming, and vibrant communities.

Jennifer Sisson, OALA, CSLA, RPP, MCIP is a Landscape Architect and Planner with 13 years of professional experience. Jennifer is the Team Lead for WSP’s landscape architectural studio based in Oakville, passionate about improving wellbeing through context sensitive design and master planning, as well as preserving significant heritage features and protecting the environment.

Junfeng (Max) Li, OALA, CSLA, MLA, PMP, APALA, ISA , LEED AP®, has 10 years’ overseas and local experience in designing, planning, and construction. As an integral member of WSP’s Landscape Architecture team in the GTHA, Max focuses his practice on transit infrastructure, residential and commercial mix-use developments, and health care facilities.