Round Table: Connecting our inner and outer landscapes

Moderated by Real Eguchi, OALA (retired)

BIOS/

Maggie Forgeron RSME/T, ExAT, TTPPD-Cert. (NBS), RYT 200, is a professional dance artist and teacher, Expressive Arts Therapist, and Kripalu Yoga teacher. Maggie is an advocate of leading-edge movement research and peer exchange. She is most passionate about body-based expressive arts approaches, exploring the possibility for renewed health and expanding the parameters of knowledge of the discipline of art and dance. www.notjustanybodypart.ca

Isaac Crosby also known as Brother Nature, is of Ojibwe and Black Canadian heritage. He comes from unceded land, 20 minutes south of Windsor, Ontario. He is the current Indigenous Urban Agriculturist at Evergreen Brick Works, where he uses his traditional farming, blended with his Horticultural Technician studies from Humber. The blending of the two has given him a chance to teach others how to care for the earth and grow great crops. He is also on CBC radio once a month on Fresh Air, and has YouTube videos called “Gardening with Brother Nature.”

Dr. Mariko Uda is an ecologically-minded writer/illustrator, speaker, and consultant, with a background in biology and chemistry, architecture, and civil engineering. She holds a PhD in civil engineering from the University of Toronto, focused on the design of sustainable and resilient communities and cities. As “ecomariko,” she aspires to write informative and delightful books that educate, inspire, and empower. Her debut, all-ages picture book Where does it all come from? Where does it all go? Toronto’s water, energy, and waste systems helps us rediscover our environmental connections despite living in a city. www.ecomariko.com

Dr. Mark Hathaway, PhD, is an author, educator, and researcher who has worked in non-profit organizations focused on sustainability and social justice in both Canada and Latin America. Mark is the Executive Director of the Jesuit Forum for Social Faith and Justice and the principal author (along with Leonardo Boff) of The Tao of Liberation: Exploring the Ecology of Transformation (Orbis, 2009) which integrates perspectives from economics, ecology, social justice, spirituality, and post-modern cosmology. In addition to teaching as a sessional lecturer at the University of Toronto, he is a visiting professor at several Latin American universities, and a faculty member of the Earth Charter Center for Education for Sustainable Development based at the UN Peace University in Costa Rica.

Dr. Nathaniel Charach is a Toronto-based psychiatrist, permaculturist, and food forest advocate whose interests focus on healthy connections with respect to self, others, and nature. He has written and presented on the topic of eco-anxiety and the importance of addressing our underlying sadness and grief. His clinical work focuses on the healing power of groups, and he is in the process of developing a healing garden to simultaneously address mental health, food insecurity, and healthier agricultural practices to address the climate emergency.

Real Eguchi, OALA (retired), was a principal of Eguchi Associates Landscape Architects/bREAL art + design for over 30 years. His current interests include sustainable beauty, embodiment, awe, and equanimity. He believes the design of lived-in landscapes must promote a healthy reciprocal connection between the human world and more-than-human world. As a survivor of the cultural genocide and incarceration of Japanese Canadians, Real views nature as a partner in his own journey towards wholeness and healing from racism and attachment/existential/ intergenerational trauma. Real believes that, to holistically address environmental issues, it is critical to accept that humans are unexceptional, mortal creatures.

Real Eguchi: I want to explore how landscape architects can create lived-in landscapes that deepen our emotional acceptance and spiritually-based understanding that we are sentient, mortal creatures, cohabiting and inter-connected with other species.

So how did we become disconnected from our outer landscape? How do we allow the outer landscape or the more-than-human world to connect with us so we can all heal? How do we reconnect in a reciprocal manner? How do we become whole?

Isaac Crosby: My view of the world and how I was raised is to look at us humans as the ‘two-legged,’ and the rest—the so-called animals—are the other sentient beings out there that share this earth with us as the ‘four-legged.’ And we are all destined to either live together or die together. We, as the two-leggeds, as humans, have ventured off our path. We neglect our responsibility when it comes to taking care of this world and taking care of the four-leggeds. So we’ve become disconnected with the outer landscape, because we have fallen into the trap of capitalism.

If our outer landscape is in chaos, that means that our inner landscape, as two-leggeds, is in great chaos. We’ve got to find a way to calm that and get re-connected to the web of life in order for us to move on, to have this world secure for future generations.

Mark Hathaway: I think one place that I’ve found helpful is the whole field of ecopsychology, which is a little bit different than environmental psychology: it examines the psychological roots of our disconnection from nature.

We live in houses separated from nature. We go to schools behind walls as opposed to something like a forest kindergarten. We are missing how people at one time would have learned with an elder out on the land. That’s not how most people in Canada learn nowadays, we learn behind walls.

It is also related to how we raise children. If a baby cries, you don’t leave it in its crib to cry. Yet, for many settler Canadians, we came to see that as the normal thing to do.

Maggie Forgeron: A lot of this is related to systemic, self-division that comes from what we call Cartesian dualism—the moment when the body became separated from the head. And this is the moment when the body became a machine for production. This focus on production, on technology, was meant to improve our lives. Medicine was meant to expand our life expectancy. Now we’re faced with the biggest health crisis of our time. So what the heck happened?

When we experience disconnection from ourselves, it becomes a disconnect from our thoughts, feelings, our six senses, and much of what makes us who we are. And it stands to reason this split also extends to our relationships to other people, and also the environment, the spaces and places in which we move. It just points to the fact that we’re very much living from the neck up. So my work in movement based expressive arts therapy is really all about a process of living in our bodies again. It’s a balancing endeavor between the head and our sensing and feeling bodies that can then extend out to our relationships and the environments we create.

Nate Charach: The disconnection is, in part, a response to trauma. We clearly see, when people have been traumatized, they disconnect from the situation, because that is adaptive in that moment, because to be present is just too unbearable. And I think that can be very clear in an overtly traumatic situation. But, as Mark was mentioning how we sometimes treat our child who is crying, and how we treat emotions in general, often we tell a child, “Oh, it’s okay, stop crying,” as though that is supportive. In fact, the child is crying for a reason. In a way, every time we invalidate the experience, we’re teaching them to not listen to what their body and their emotions are telling us: teaching them to create that space into separate things.

So the process of reconnecting is actually one of facing fears in what we’ve been told is wrong with us in some way, when it’s actually our natural state of being.

RE: I wanted to mention speciesism that speaks to the idea that humans have moral rights over other animals, and it’s reflected in how we treat those other species. And something Maggie knows about and to my understanding, is that when Europeans spread out across the world, they witnessed people celebrating through ecstatic dance, a dance form which is part of Maggie’s practice and mine. And I understand they viewed this form of dance as animal-like, so not only are non-human species ‘othered,’ some humans are, as well. Perhaps this is where social and ecological issues intersect?

MH: I think it’s the domination and the hierarchical mentality.

RE: So how do we get back to being more integrated? I’ve been to City of Toronto public meetings about coyotes. I just don’t know how we’re going to get to that point of cohabitation.

IC: Cohabitation with our four-legged brothers and sisters is inevitable. Because we keep building homes and spreading out into where they live. They’re doing what is natural to them. They’re living with the two-legged humans. Usually, when they see humans, coyotes turn the other way. It’s we humans that have to learn how to re-live with nature. With or without human beings, nature will live on. So we either get over our egos and learn how to live with nature and support her and the natural beings that are out there, or we will eventually be swallowed up by nature.

RE: Mariko is using the book she recently wrote and illustrated to help reconnect us to our local landscape and offering related classes as well. Mariko, what have you noticed about the awareness people have in terms of some of our basic human needs?

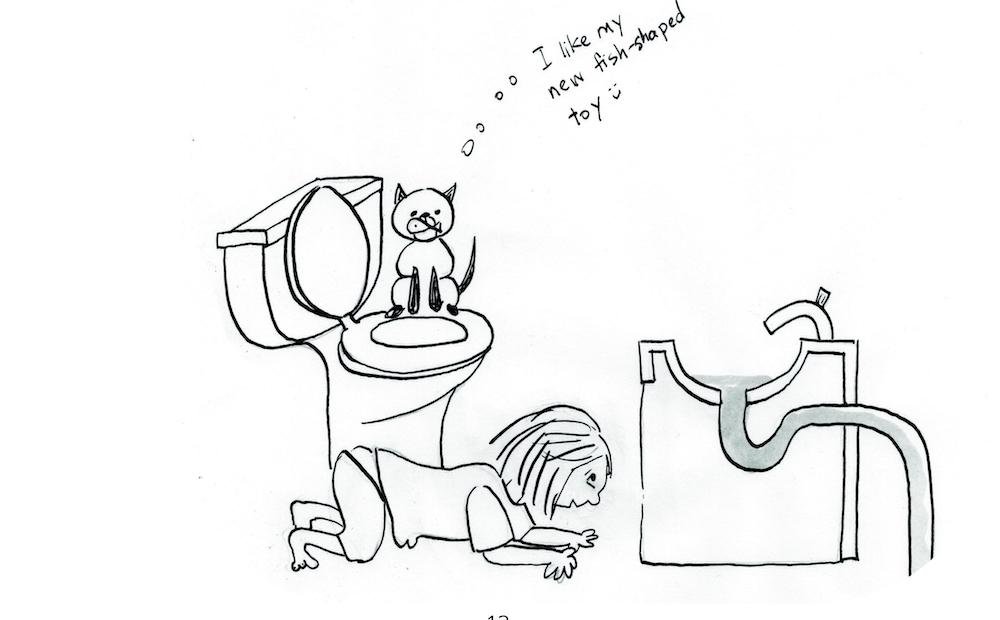

Mariko Uda: Yes, the book is Where does it all come from? Where does it all go? Toronto’s water, energy & waste systems. It’s a picture book for kids and adults. It helps people understand where their water comes from or where their sewage goes, for example. A lot of us don’t know these things.

With sewage, and back to the dualism/disconnect point, I think we tend to not want to see our waste. We just want it to go away, and to see ourselves as humans, not animals. So we have clean and dirty as part of that dualistic thinking and our infrastructure reflects that. You just flush the toilet, the toilet looks nice and clean, and the waste goes somewhere we don’t see. Our infrastructure encourages the sense of disconnection.

Unless we know a specific person or place, we can’t have a relationship because it’s all very vague. And we all walk around in the city. So what I’m trying to do with my book is specifically name the place where things are coming from and where they are going. And that’s kind of the start of a relationship.

RE: If we are so disconnected from all of this, it will be a challenge to understand our bodies as natural and ourselves as animals.

If the inner landscape lies within our skin, what are the basic needs of this landscape? How do we heal, develop greater inner wholeness and connectivity as uniquely sentient, yet unexceptional mammals?

NC: One of the things I see often is the differences between re-experiencing things in a way that’s healing versus more traumatizing, and whether we are activating the fear and anger pathway, which leads to the disconnection, or we’re able to activate the sadness and love pathway. Our environments can play a crucial role in a challenging setting, while helping us feel safe. If the person can feel safe, and therefore able to access the sadness and love pathway, they are in an environment that’s going to offer a curiosity towards nature that feels safe to explore. From there, we can move towards that healing place and reconnecting with that part of ourselves.

So, if the landscape that we’re in, for example, can show us what watershed we’re in, or even just where our food is coming from, or where the compost pile is, that can nurture the curiosity within us, rather than make us feel afraid. That’s the root towards helping people step in the direction of also reconnecting with the inner landscape, rather than feeling afraid and pushing it away.

MH: There are studies about what could be called self-transcendent emotions, including things like gratitude, love, and awe. Instead of acting out of duty, we need to act out of a sense of care and connection. This is reflected in something like Joanna Macy’s The Work That Reconnects, which promotes connecting with gratitude before we confront the pain in the world, because if we begin with the pain right away, we just start shutting down and experiencing fear.

Some practical things strike me about that. I’ve worked with students in my Ecological Worldviews course, and the Earth Charter course, where I get them to do an ecological meditation: they have to find an other-than-human being, broadly defined. It could be a rock. I don’t say where sentience lies. If they find sentience in a rock, that’s fine. It could be a bird, a tree. an ant. And they just spend time trying to connect with that other-than-human being. I encourage them to let it be their teacher and ask themselves ‘what is this other being trying to teach me as a being?’

So there are landscape-related activities that are practical ways to start reconnecting and feeling that wonder and a bigger sense of self, where we’re drawn out of our little ego into something broader.

IC: I am thinking about COVID. There’s something I realized that I think we forgot about with respect to the beauty of nature. When human beings stepped away for a while, nature came back and started to re-heal herself. And people said, ‘Wow, look at that. I can actually see a blue sky. I can hear those birds singing again. I can see a fox running.’ People were so happy with all of this, but they are now forgetting. We’re starting to walk back that path where we’re going to start polluting the Earth again.

MF: I really hope we build on the outdoor momentum we’ve built during the pandemic. Looping it back into the subject of lived-in, landscapes, I think it’s going to be helpful to have infrastructure that reminds us nature is what saved our mental and physical health during this time. My expertise is in movement and dance, but I think natural landscapes have a similar effect on the integration of the brain and the body. We have a visceral response in nature. We have stressed-out days where we don’t know if we’re coming and going, and something as simple as being in touch with a walk in the woods or being close to a body of water just automatically melts the stress away. We’ve discovered quite a bit of that during the pandemic.

RE: What about the notion that the healing could be reciprocal, that it shouldn’t just be about humans and how we heal through nature-based experiences, but asking what we are giving back?

MH: I think that’s one of the differences between environmental psychology and ecopsychology, in that ecopsychology has always said that it’s not about using the environment as a therapeutic tool. It’s about re-establishing a relationship of reciprocity, so we can heal both ourselves and the more-than-human world at the same time.

RE: What might be the role of Indigenous communities and their worldviews in helping us to reconnect or improve the relationship between our inner and our outer landscape? And what role does spirituality play?

IC: Here’s the thing about the role of Indigenous voices here and abroad—remember, everyone is indigenous to somewhere. It just so happens that a lot of people are not indigenous to the Americas. Let’s start there.

I always tell people to go back and re-learn what your people did with the environment and how they lived in harmony with the environment. They will find a lot of answers there and realize Indigenous peoples here have a lot of the same ideas. What happened here in the Americas in the course of the past four to five hundred years is a lot of those ideas were disrupted.

Now, after these four to five hundred years in this part of the world, people are waking up and realizing what you do to one part of the web, you eventually will do to yourself, and we have shot ourselves in the foot for far too long because we’ve allowed this disconnected ideology to take over and take root.

We need to sit down and talk to Indigenous people. When you hear Indigenous people talk about “land back,” it’s not getting the land back so we can develop and build homes, we want to take the land back so we can heal this land again.

Spiritually speaking, whatever I do for me when I’m planting and when I’m looking at how to take care of this Earth, everything comes from spirit. My spirit walked with her first, talked to her first. Before I undertake any planting, I always make sure I sit down and talk to Earth, feel Earth. Earth speaking to me is about a little inner knowing. It is this little whisper that speaks to me. And that’s how I connect to the Earth and how I know what needs to be done.

RE: When I first heard Isaac speak, he mentioned two-eyed seeing and I didn’t know what the term meant. And I think, Maggie, you combine ballet and ecstatic dance in your practice, perhaps the two opposite ends of the spectrum and perhaps a combined expression of traditional knowledge and Western science?

MF: My background in contemporary and ballet dance certainly has embedded within it the systemic division we’ve been talking about. It’s also interesting that, since I’ve started more exploration in movement-based expressive arts therapy, I see more possibilities for a new understanding of aesthetics and beauty.

My mentor, Ken Otter, once reminded me of such things as the miracle of breath, sensuality, the changing expressions of life, the mystery of birth and death, and the infinite expanse of stars.

There’s so much needed focus on trauma, loss, grief, divisiveness, and the fractured world that we live in. I just want to insert right now that I love that you’re trying to make this shift towards sustainable beauty and healing people on the planet.

RE: How does ecstatic dance connect you to Earth? And what do the students who come for ballet think about this?

MF: It connects to the wild animal that we all are, but that doesn’t necessarily need to negate the need for intellect and function on our planet as well. Maybe that’s something to contribute to lived-in landscape design as well: that it’s not a one or the other, it’s a both and.

RE: How can landscapes be developed, from a small balcony garden to a large ravine-park, that can help to deepen our individual, healthy connection to the human and more-than-human world?

MH: Someone mentioned education. When I look at our schools, I see all these big open fields. I think of all that space and ponder how wonderful it would be if students could be gardening and growing food or even a small forest or a forest classroom or something. How could the landscape of the schoolyard change, and also change the form of education, so that people reconnect to Earth?

IC: The gardens can happen. Spruce Court Public School in Toronto has a great teacher-parent buy-in when it comes to their garden, and it’s beautiful. When I was working there with Green Thumbs Growing Kids, I would always make sure to ask the kids where carrots or potatoes come from. If they said that potatoes come from french fries at McDonald’s, we were planting potatoes that day. If they said carrots came from a bag in a grocery store, we were planting carrots.

RE: Shifting topic a bit, how we can apply the thoughts around education to our ravines? The ravine near me is filled with Norway Maples, phragmites, DSV, garlic mustard. People love nature and the ravines, but don’t seem to know what is there and the City doesn’t have the resources to deal with it.

IC: The strategy with the ravines is actually changing within the City of Toronto. The City of Toronto has now started to listen more to environmental groups. And the whole talk is about taking parts of the ravine, sectioning them off, and allowing environmental groups to go in there and tackle all the invasive species. At Brick Works, my team and I designed a program where we spend the next couple of years going into the valley, taking the nuts and seeds from all the native tree species, growing them at Brick Works for a couple of years, and returning them back to the ravine.

RE: What examples from your professional and personal practices would you like to share that can help others heal by connecting their inner and outer landscapes towards the evolution of an ecologically and socially just world?

MF: For me, it always comes back to the body. We need to realize that our bodies are a part of this planet… we are in it and we are of it. Until we realize that, we’re not going to be able to truly appreciate, for example, the beauty in the ecological connections of a tree. Let’s find the joy in this.

MU: I would agree that joy is very important and that we need to find it in what we’re doing to help the planet. Otherwise, it’s not really going to help. I also think about our relationship to water and Lake Ontario and how we turn on the tap and we think about H2O as a commodity. Somehow, it’s become a commodity when it’s coming out of our tap, but if you look back through the pipes and how it gets to your house, it came from the lake. So the water coming out of your tap is Lake Ontario.

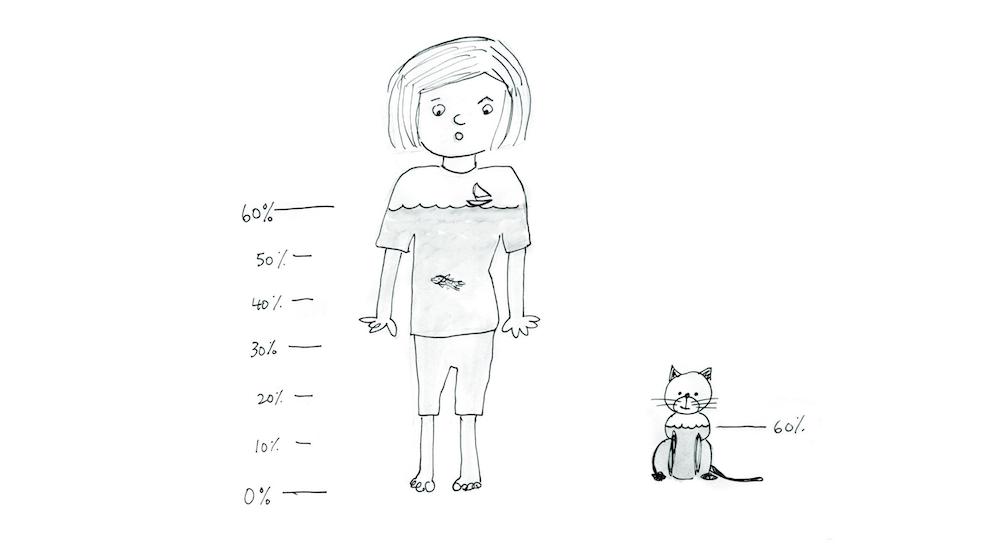

If we’re drinking mostly tap water, rather than bottled water, and our bodies on average are 60 per cent water, we’re actually 60 per cent Lake Ontario: we really are the lake. There’s no division, and I try to emphasize that.

NC: I fully agree with Maggie that, if we aren’t reflecting on our inner landscape, the changes we are making in the outer landscape actually don’t end up being significant. At the same time, sometimes just being in that outer landscape and allowing it to affect us helps us to then change the inner. Again, it’s that reciprocity. That process can become a regenerative kind of circle. Hopefully that ties in with thinking about designing landscapes. How can we design landscapes that help bring about this interchange we want to see in the world?

MH: I facilitate an exercise where I ask my students when the last time was that they were alone with nature? I then go through the exercise and ask several questions until I get to the point where I say, “Who were you with when you were alone in nature?” And then, “Is really possible to be alone in nature?” I think we still have that mindset of being separate from the more-than-human.

IC: I’m realizing something for landscape architects: that they have the responsibility to find the soul of the designed space and reveal it in a way that human beings can appreciate. That means sometimes the designer is going to have to let go of their landscape architect brain and find their spirit or inner landscape, so the soul of that space can come forward.

MU: After a long time involved in environmental work, things often don’t always go the way we hope for. But what’s important is we are at least moving in a healthy direction and that people are happy and there’s love.

RE: When you talk about moving in a healthy direction, you’re talking about evolving connection and relationships. I think that’s what we all talked about here today. I’d like to summarize by concluding that we seem to all agree that landscape architects need to create environments that encourage people to appreciate the gift of an embodied life, so they willingly, holistically, and reciprocally engage with their local landscape, Earth, and community. This way, basic human and more-than-human needs can joyfully and equitably be met.

Thanks to Real Eguchi for coordinating this round table.