The City is a Forest: Building cities that are smart, green, and connected

Text by Shannon Baker, OALA

All over the world, cities are going digital. From autonomous vehicles to smart traffic signals, to trash cans with sensors, the internet of things has caught urban life in its web. With promises to transform urban mobility and streamline maintenance operations for City staff, the allure of the Smart City is undeniable. The UN projects that, as urbanization intensifies, the human population could add another 2.5 billion people to cities by the year 2050, meaning that around 68 per cent of the world’s total population will be city dwellers. This intensification places enormous pressure on the systems of cities, as roads become choked with traffic, water and wastewater systems struggle to meet the demands of a growing population, and electrical grids stretch to capacity. Smart cities promise a panacea for all of the problems plaguing the modern city, claiming to have positive impacts on all sorts of indicators including environment, human health, physical performance, economic benefits, and social connections.

The Smart City promises to make the urban life more liveable.

Many politicians and city managers find the draw of smart city technologies irresistible. Scanners and sensors are to the modern city what the foosball table and draught kombucha tap are to the downtown office: symbols of progress and collective cool that are key to competition on the global scale for the world’s brightest minds. There are many advantages to the high tech high street to be sure, but smart cities also come with a number of challenges centred around privacy and data security. Connecting urban systems to the internet of things also makes them vulnerable, as the recent hacking of a major US energy pipeline made strikingly obvious. Not only is technology vulnerable to cyber threats, it can also simply break down, or become obsolete, requiring upgrades and rebuilds to ensure that urban systems adapt and remain state-of-the-art. When public utilities, street lights, garbage receptacles and the like are all interconnected, an entirely new IT work force is required to operate and maintain them. Sometimes, smart city solutions can feel like tech for tech’s sake, with no clear aim but to digitize the analog. In more cynical readings, they can be seen as a bid to monetize personal data, and more deeply entrench crypto capitalism.

We are living in the digital age, and it is unlikely that intelligent solutions to urban issues will disappear. In an increasingly complex world, however, one in which the importance of nature and us humans’ place within it are now well understood, surprisingly few of the emerging urban technological solutions relate to natural capital, and the urban ecosystem. Innovative thinkers such as Dr. Nadina Galle are beginning to push those boundaries, through what Galle refers to as “The Internet of Nature.” Galle is involved with Treemania, a company that seeks to bring together “biology, trees, soil, technology, artificial intelligence and innovations to make the management of urban green space more sustainable and efficient.” Using a series of interconnected tree moisture sensors, Treemania connects urban street trees with the people who care for them, from volunteers to city maintenance crews. The technology gives newly planted trees the power to ask for a drink when they need them, and that has had impressive impacts on the survivability of the trees.

The City of Melbourne, Australia, recently gave 70,000 of their trees email addresses in a similar effort to connect people with trees, so citizens could report problems with tree health and request maintenance. Instead of just sending a note to say that tree #5467 needed a little water, the City was overwhelmed with an outpouring from around the globe. People wrote love letters to the trees, asked the trees the meaning of life, and sometimes just made bad jokes. Clearly, people wanted to connect with the trees, and technology allowed them to feel a sense of connection on some level. Perhaps they began to see trees with new eyes.

It’s commonly understood that when people feel connected to something, they are more inclined to care for it, and may assume a more active stewardship role. Apps like PlantSnap, NatureID and iplant can help to cure plant blindness, a condition in which people fail to notice or value plants in their environment. This condition can have far-reaching consequences for plant conservation, as it can lead to apathy in the face of environmental threats. Giving people the tools to be able to ‘see’ plants, and their human-like characteristics, endears them to the plants, and makes people far more likely to support conservation efforts.

Perhaps, with these new technologies connecting us with nature in new ways, we might also learn to look to old technologies with new eyes, maybe even things we don’t typically view as technologies, but are, in fact, the most miraculous webs of interconnection on the planet. Forest ecologist Dr. Suzanne Simard has been doing groundbreaking work in this area, revealing what some call the ‘wood-wide web,’ a complex network of bacteria and fungi that trade nutrients between soil and tree root in symbiotic relationship. Simard’s work has allowed us to see the forest, and the living beings that make it up in a wholly different light. Trees create their own civilizations, their own cities in the forest. They communicate with one another, they protect one another, they recognize their own kin. Simard has revealed that trees are often connected to one another through an older tree in the community, one she refers to as the ‘mother’ tree. Mother trees act like a router in the wood-wide web, picking up and amplifying signals.

The architect Christopher Alexander emphatically stated “a city is not a tree” in his 1965 paper analyzing urban structures. A city may not be a tree, but what if a city could be a forest? Not just a forest in the way we tend to think of the urban forest today, but a complex and interconnected ecosystem that supports a myriad of rich and diverse life forms, not just human, that are deeply connected to the soil, water cycle, and seasons? There are some tools that begin to scratch the surface of this work, soil cells that allow for root connection and respect the importance of soil structure, deepening understanding of plant communities and their complimentary fungal friends, but we have only just begun to understand the complexity of the forest.

What if we started designing our cities like they were forests, embedding the intelligence of nature in all of our urban systems? What if we began to imagine smart, green cities that operated as ‘The Internet of Nature?’ Perhaps then we would begin to understand what liveability truly means: respecting the complex web of connections that make life thrive, and co-existing in deeper connection with all other living things.

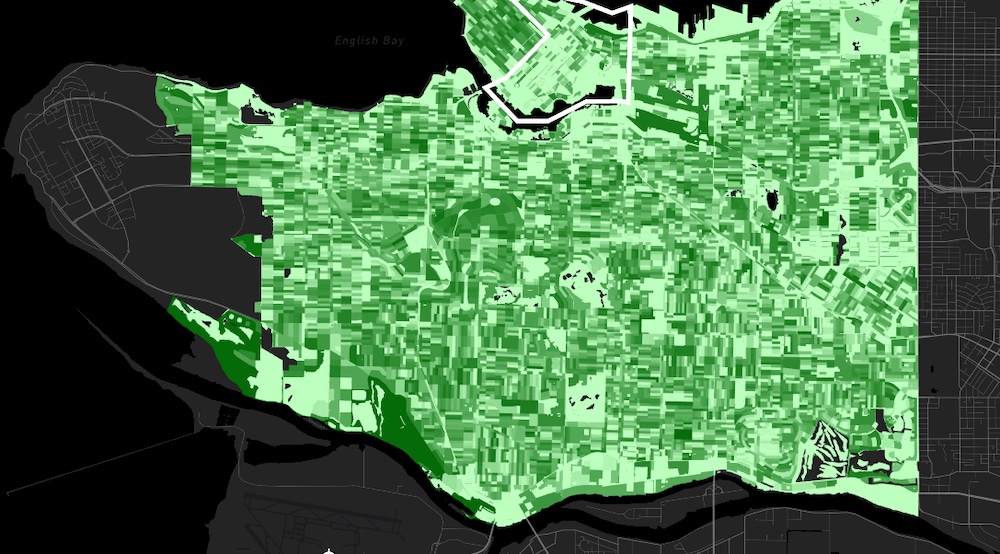

- LiDAR for monitoring canopy quantity and forest structure.

- Remote sensing and satellite imagery for monitoring canopy cover.

- Smart building and green-grey infrastructure integration for energy savings and building performance.

- Development and land-use planning decisions based on ecosystem services trade-offs and information acquired from complementary data sources.

- Plants as biosensors for ecosystem resilience.

- Aerial seeding for urban reforestation.

- Virtual collection of plant pathology information for pest detection and diagnostics.

- Sensor networks for monitoring stormwater, urban heat islands and air pollution uptake.

- Street-view imagery and AI for green cover quality and management.

- Biodiversity enhancement through volunteered geographic information.

- VR and AR for green space perceptions.

- Sensor networks for monitoring the effectiveness of stormwater management strategies and soil quality.

- Social media platforms for public values elicitation about green space design.

- Wearable technologies for health management in response to green space exposure.

- Blockchain and cryptocurrency for greening initiatives.

- Robotics for green infrastructure maintenance.

- All ecosystem intelligence stored in the ‘cloud’.

- Real-time communication between IoN network and city.

BIO/ Shannon Baker, OALA, is a landscape architect currently engaged as the Project Director for Parks and Public Realm at Waterfront Toronto.