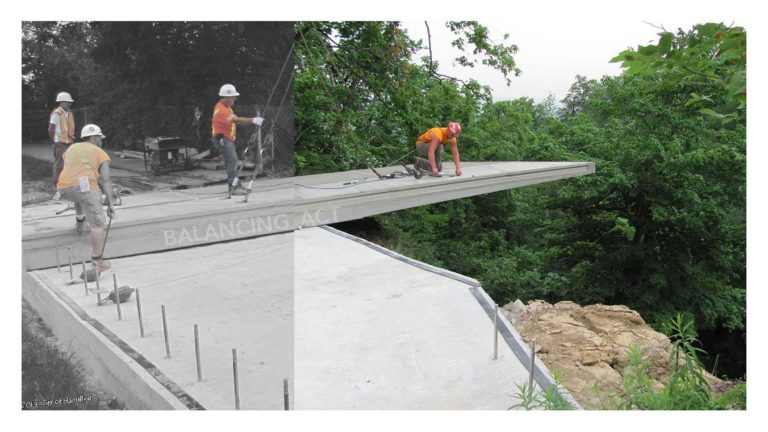

Balancing Act: Providing public access to Hamilton’s waterfalls

TEXT by Jonathan Michael, OALA, Kathy Smith, OALA, and Allan Neal

The ultimate goal of design, by perhaps the simplest definition, is to solve a given problem. In their spatial design work, landscape architects solve a multitude of problems, balancing the needs of clients, associated budgets, user groups, and the environments in use. In this way, landscape architects are mediators of competing interests which in themselves pose a unique design challenge. This challenge is only compounded as public demand on open space and natural areas rises—an outcome that has become particularly acute in Ontario’s urban areas along the Niagara Escarpment. One such area is Hamilton, which is fortunate to have its unique geographic position at the western edge of Lake Ontario, where the entire city is bisected by the escarpment’s path. The slopes, cliffs, and valleys formed by this geological feature, the same one over which flow the Niagara Falls at the nearby Ontario-US border, affords the city numerous natural forested areas for locals and an increasing number of visitors to enjoy. With this increased demand, however, comes an amplified need for thoughtful, proactive planning and design that can balance the demand for access to these sites with their inherent carrying capacity, presenting an “opportune problem.”

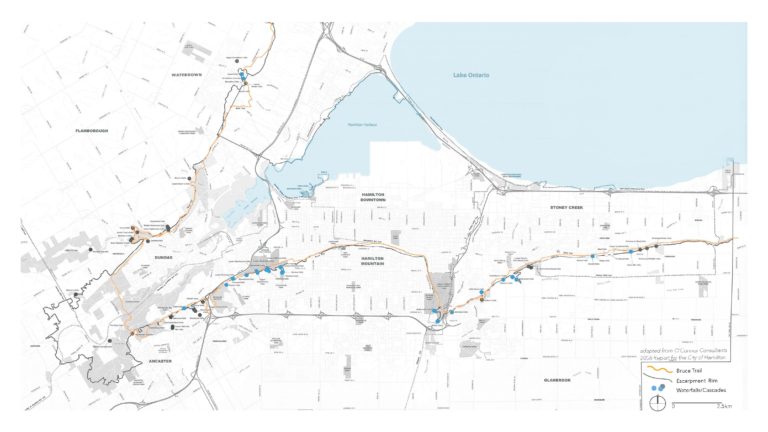

Designated in 1990 as a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve, the Niagara Escarpment is a roughly 1600-long limestone ridge that stretches from southeast Wisconsin, meanders 750 kilometres through Southern Ontario, and terminates near Rochester, N.Y. The formation of the escarpment began 450 million years ago as the bed of a tropical sea called the Michigan Basin. Over time, sediments at the bottom of this sea were compressed into rock, limestone, and shale. As waters disappeared, the escarpment became exposed and subjected to a long period of erosion by weather, ice, and streams. The Niagara Escarpment now sits approximately 4-5 kilometres inland from Lake Ontario within the City of Hamilton and varies at heights around 100 metres, relative to the lake. Thanks to its location along the escarpment, Hamilton is home to 156 waterfalls, according to The Smithsonian. This number has been disputed over the years but is nevertheless enough to crown Hamilton as the waterfall capital of the world. The Bruce Trail, which traces the path of the escarpment through Ontario, is an essential outdoor amenity that provides almost continuous access to the escarpment’s natural features and a vital passage to Hamilton’s numerous waterfall areas.

As geo-tagged social media platforms gain traction, so does exposure of these areas. Individuals ranging from adventure seekers to bloggers will travel great distances to catch a glimpse and strike a pose by the falls. Selfies are posted on ‘the ‘Gram’ and other social media platforms, showcasing these picturesque landscapes. What their subjects aren’t always aware of are the potential ecological impacts and physical dangers involved in accessing these often-prohibited areas, nor the bylaws set in place to protect them. For example, from March 2020 to March 2021, 740 charges were issued by Hamilton bylaw enforcement, the vast majority of which were given to people entering prohibited areas. This unsanctioned access can result in visitors putting additional strain on environmentally sensitive areas, or finding themselves in dangerous situations that require an emergency response and even rope rescues. In 2020, Hamilton EMS responded with 20 rope rescues on the Niagara Escarpment, almost double from the year before. Throughout the pandemic, visitors to these sites have increased exponentially. How can we as designers and governing agencies balance the increased public demand on these sites while preserving their ecological integrity and human-user safety?

Municipal Process

Municipalities and other governing bodies are particularly faced with this challenge. This reality is especially true in Hamilton, where the near-continuous presence of the escarpment and its natural areas through the city make it impossible to fence off or otherwise restrict access to these ”opportune problem” areas.

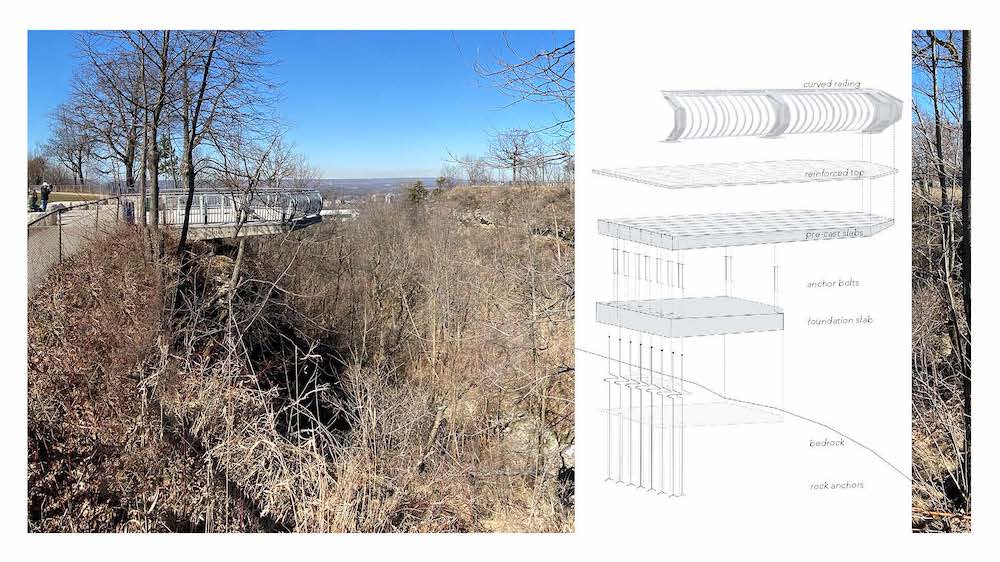

Accommodating safe, sanctioned access to these areas in a timely manner is further complicated where competition for already thinly-stretched municipal budgets can be fierce. In spite of this, Hamilton has successfully constructed several waterfall access overlooks and is continually looking to add more where necessary, and where funds allow. However, to do so in a timely manner is perhaps the greatest hurdle, given the long permitting and wide consultation processes with various stakeholder groups and external agencies that are necessary, and, to be sure, warranted; no municipality would want to rush these kinds of projects, at the risk of adversely impacting the health and well being of public users and the natural environments that they are increasingly looking to explore. If Hamilton’s past waterfall project deliveries are any indication of future endeavours, the timeline for constructing a sanctioned waterfall access project could take anywhere from 5-10 years.

Hamilton, like other municipalities similarly faced with their respective “opportune problems,” must work proactively to address these issues in the short term, while longer-term solutions are forged. Social media, one of the ostensible causes of the exponentially ramped-up visitor influx to Hamilton’s waterfall areas, might be flipped to become a solution, as an education mechanism that could inform visitors about the delicate and potentially dangerous environmental areas they are exploring. More traditional posted interpretive signage can certainly help as well, although at an added up-front cost. Post-occupancy evaluations on constructed amenities, or post-campaign evaluations for public education measures, might also prove valuable, working with bylaw and emergency services to gauge whether implemented measures are in fact working to keep people on the trails. And, of course, although the public is not typically keen on paid parking for open space access (the effectiveness of which could be easily debatable in urban Hamilton, given the myriad entry points to its natural escarpment areas), visitor management and parking controls, such as a reservation system, have been successfully implemented at various sites in Hamilton that fall under Conservation Authority jurisdiction.

Conservation Authority Perspective

Unique to Ontario, Conservation Authorities (CAs) are local watershed management agencies that deliver services and programs to protect and manage impacts on water and other natural resources, in partnership with all levels of government, landowners, and many other organizations. The core mandate of CAs is to undertake watershed-based programs to protect people and property from flooding and other natural hazards, and to conserve natural resources for economic, social, and environmental benefits. There are 36 CAs operating in Ontario, each with its own Board of Directors comprising members appointed by local municipalities. CAs are either charitable or non-profit organizations legislated under the Conservation Authorities Act, 1946, and vary in size depending on the watershed they serve. CAs receive funding through municipal levies, self-generated revenue, and federal and provincial grants.

Hamilton Conservation Authority (HCA), situated at the western end of Lake Ontario and Hamilton Harbour, is the region’s largest environmental management agency. HCA has operated for more than 50 years in the community. Our watershed comprises two member municipalities: the City of Hamilton, and Township of Puslinch. To date, HCA owns and manages 4,484 hectares (11,079 acres) of land in public trust and is responsible for approximately 56,800 hectares (140,355 acres) of watershed area. Our conservation area lands are unique pockets of local green space that help the city and watershed thrive and connect people to nature.

HCA’s lands are increasingly becoming the only areas in the Hamilton watershed where people can experience nature, a watershed accessible to over six million people living in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. Population growth is increasing, as is demand for access to natural and recreational areas, including access to waterfall areas along Hamilton’s portion of the Niagara Escarpment. Of the more than 100 waterfalls in Hamilton, six of the most popular waterfall sites with public access are situated on HCA lands.

During the pandemic, public visitation to HCA’s conservation areas reached all-time highs, creating challenges with parking, public safety, litter, and sanitation. Several design and administrative controls were required to be implemented in a coordinated effort to assist with traffic control and public safety. Design measures included the installation of parking entrance gates, fencing, upgraded trail surfaces, and improved site signage. Administrative controls included social media messaging, site security for traffic control and parking, a visitor reservation system to help manage visitor numbers, visitor shuttle services to parking areas (pre-COVID), and alternative transportation promotion (municipal transit, walking, cycling, car-pooling). HCA continues to assess ways and means of protecting natural areas and connecting people to nature and relies on the services of professionals such as landscape architects to achieve these objectives.

Summary

The opportune problems that increased public visitation to natural areas pose for landscape architects challenges our planning, consultation, and design expertise. This is especially true at a watershed scale, where multiple agencies have shared jurisdiction over natural areas, and where multiple groups with varying needs and degrees of associated risk are using them. Landscape architects have a real opportunity to play a leading role in solving these multifaceted problems through proactive design, attentive consultation, and cross-discipline collaboration.

BIO/ Jonathan Michael, OALA, CSLA, is a place-curious landscape architect who is happiest while exploring new environments, preferably accessed by foot, bike, and train.

Kathy Smith, OALA, CSLA, is a landscape architect with the Hamilton Conservation Authority, Capital Projects and Strategic Services division, whose work in Ontario is the happy result of a lifelong love of nature.

Allan Neal, is a Project Manager with the City of Hamilton’s Landscape Architectural Services who loves competitive sports, spending time outdoors, and all the little things the natural world has to offer.