Michael Hough: Man on a mission

Text by Kaari Kitawi, OALA

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” —Bernard Shaw

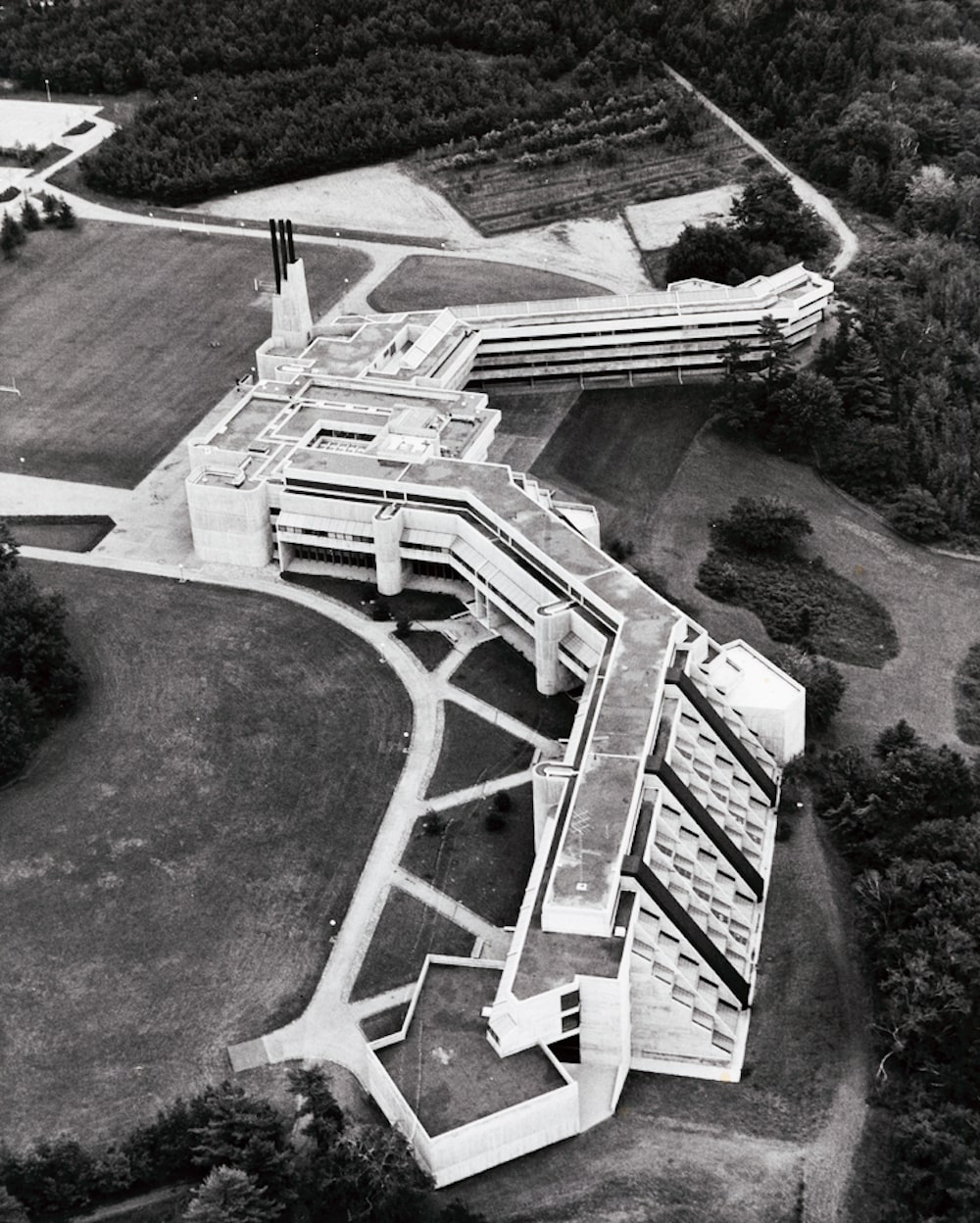

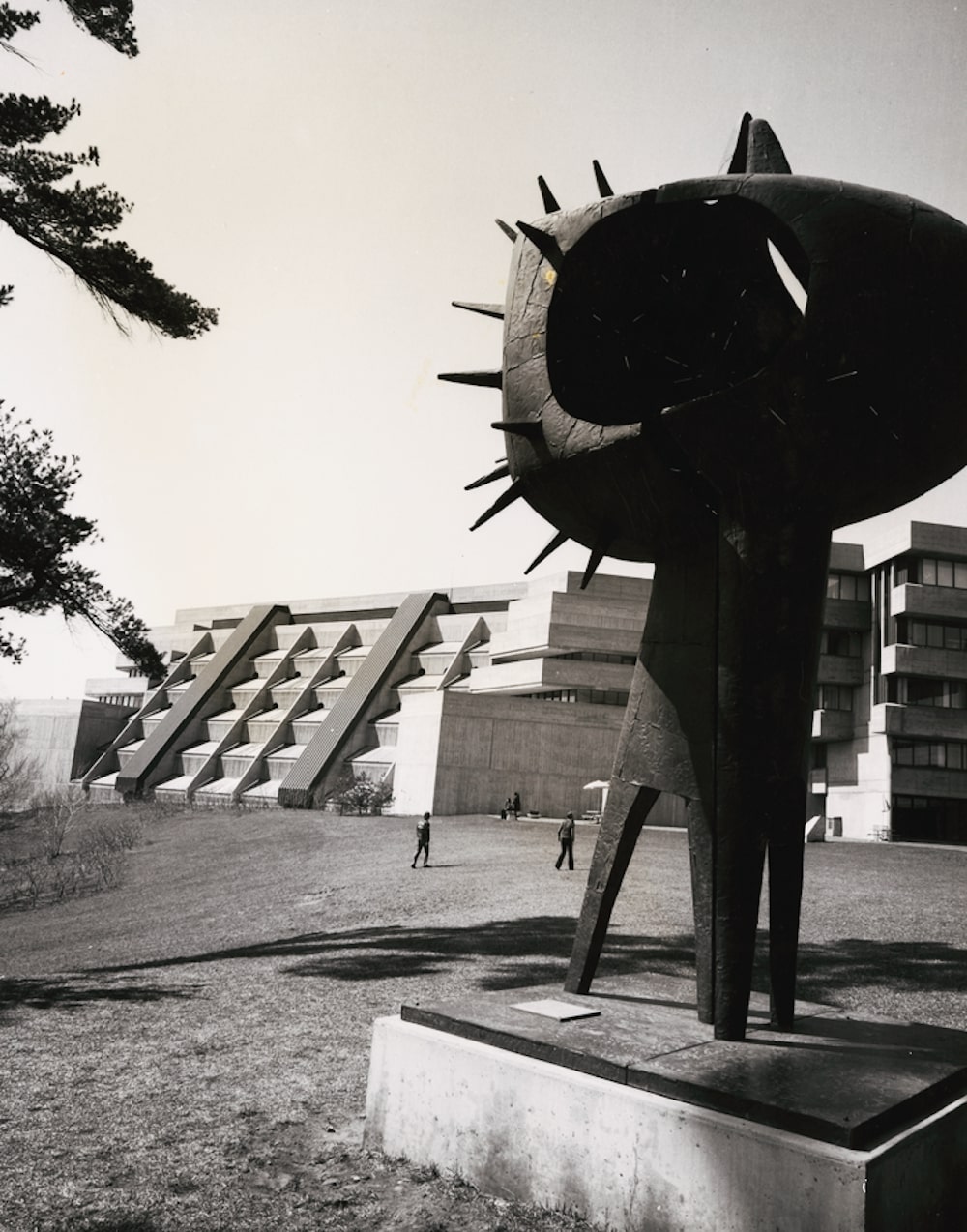

We know of Michael Hough’s famous works, like Ontario Place and University of Toronto Scarborough Campus, and of his passion for ecology, but who was he as a person? What was he like to work with? How did his practice and vision impact our profession and the City of Toronto? I sat down with a few of his partners from the former firm ENVision—The Hough Group, and his contemporaries Walter Kehm and Ken Greenberg to uncover more.

Comrade in Arms—Walter Kehm

Walter and Michael met in 1962 at Project Planning Associates. The two shared deep values of making a better society, by creating places where people of low means could have access to nature. Their relationship was further fostered when, as neighbours at Summerhill, they began challenging the City’s school design, street widening, and plans to channelize a local stream.

Playground Design

Their children attended the Deer Park School at Yonge Street and St. Clair Avenue. The school bordered the ravine but was fenced off “to keep the children safe,” while the children’s playground was covered in asphalt. Michael and Walter independently expressed their concerns to the school’s principal who dismissed them. Undeterred, the two combined efforts and built a model of the school to demonstrate how the ravine could be integrated into the school yard and made a presentation to the school board. As result of their passionate presentation, the Toronto District School Board worked with each of them, separately, on various school greening initiatives.

Standing up to City Officials

They marshalled their efforts again when Ray Bremner, the then-Commissioner of Public Works for the City made plans to bury the Yellow Creek at the Vale of Avoca, in Summerhill. The plan was for Public Works to bury the polluted stream and for the Forestry team to replant over it. Michael and Walter “fought tooth and nail” against burying the stream, arguing, instead, to treat it at the source, removing pollutants so it could be enjoyed by the residents downstream.

Pushing the Profession Forward

Michael and Walter were part of the team involved in the formative aspects of the OALA. They also worked on the Royal Commission for the future of the Toronto Waterfront. Over the years, their efforts have influenced the shift in thinking from landscape-as-ornament, to landscape as part of a natural system that contributes to health and wellbeing.

Trillium Park

When Walter was asked by the OALA to commemorate Michael at Trillium Park, he remembered how their journey started in the 1960s with their families. He wanted to recognize Michael’s constant support, his wife Bridget and their children. The vegetation would be a testament of wild nature, with native trees, wild flowers, and no mowed grass. It would be a place for all people to be in nature.

It Takes a Team—His Partners

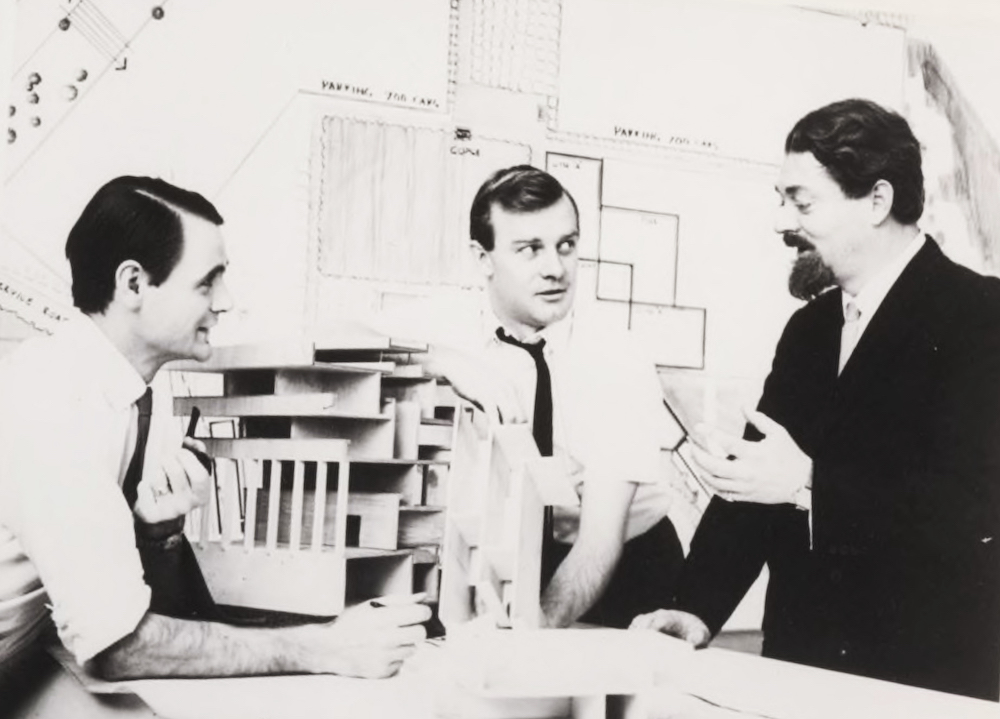

In the early 1960s, as Michael and Jim Stansbury were forging their partnership, they agreed that their practice be a blend of Michael’s “city in nature” and Jim’s “focus on erasing the snooty but silly boundaries that obstructed teams and collaboration.”1 Later, when Michael Michalski joined the firm, they broadened their focus: linking ecological science to site planning and design solutions.

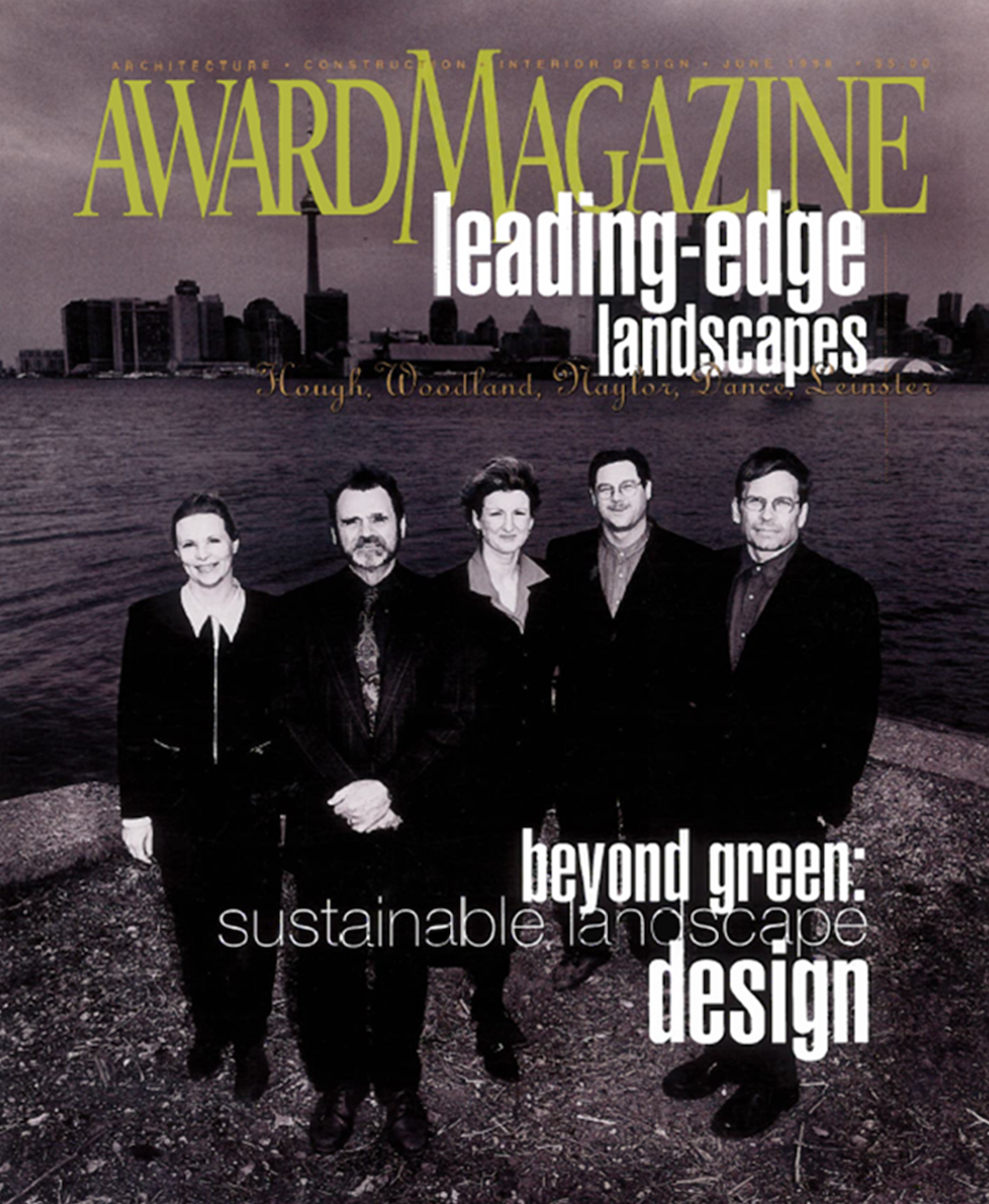

The firm’s partnership structure evolved as they attracted talented staff such as Carolyn Woodland, Eha Naylor, Ian Dance, and David Leinster. It started as Michael Hough and Associates, and finally as ENVision – The Hough Group. The talented staff enabled the firm to act as prime consultants, directing interdisciplinary teams of professionals on waterfront redevelopments, policy-oriented work as well as consulting to other professionals.

Eha describes Michael and Jim’s partnership as being complimentary: Jim ran the business side while Michael did the creative exploration. Their temperaments were also polar opposites: Jim was calm even-keeled, while Michael could be crusty if someone was not up to par. She adds that “Carolyn was the glue that held them together,” balancing the partners while still delivering “excellent, creative, innovative, and beautiful work and doing it at a level that was always pushing boundaries.”

Describing Michael

Michael’s partners describe him as being determined, relentless, and focused. He was passionate and committed to integrating “green technologies” into all his projects—which sometimes did not sit well with some clients. At his memorial, Carolyn Woodland remarked, “His unflinching perseverance, and sometimes lack of diplomacy, earned the office the nickname Huff and Puff.” Eha explains, “Once he dug his heels in or sank his teeth into something he would be relentless and be a vocal champion.” This quality, which exasperated some, won many clients over and, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, gave him influence with professional colleagues and civic leaders.

Studio Environment

True to their vision, Michael and Jim built a great studio culture—a creative think tank consisting of interdisciplinary teams of professionals. As this was pre-GIS, site inventory and science maps were manually layered to inform and formulate conceptual thinking. The team engaged in constructive dialogue, across disciplines, to develop creative solutions based in science.

When Michael was in studio, he wanted to be part the design process, and would often tweak a design concept if he felt it could be improved. This was a little frightening for staff, particularly in the final stages of preparing to tender. Eha says that with Michael there was no coasting, “You always had to be on your game.” Though he had strong ideas, David Leinster clarifies, “He was not an ego maniac, but was open to dialogue and expected the people who worked with him to be thinking a lot.”

Design Philosophy

Ecosystem Planning

According to David, Michael was interested in landscape as a bigger idea, not on a site-by-site basis. When he approached a client’s project, he thought of it in terms of the bigger plan: how could it contribute to the bigger city initiatives. He was advocating Ecosystem Planning—the idea of integrating ecology, social, and cultural ingredients in city planning. He used this approach to urban planning when he worked with former Mayor David Crombie at the City of Toronto.

Innovative Techniques

Michael was a researcher at heart and was committed to exploring creative solutions to site challenges, which were embedded in science. “Now we are so driven by budgets and trying to get things done, but Michael was quite willing to continue the fight to find the better solution,” says Ian Dance. Eha points out that this could be very challenging, because many of the innovations they were testing had no precedents.

Changing Minds

Michael was no “yes man.” If he believed that there was better solution than what the client or architect wanted, he would continue to push for it. Ian humorously remembers being a junior architect attending a meeting where Michael was passionately promoting a solution that was different from what the client wanted and wondering to himself, “Are we not listening to the client?”

Carolyn explains, “It took a lot of successful projects and putting them together with good clients to actually get people to see that there was a different way of doing things.” In describing ENVision’s work, Suzanne Barrett from Waterfront Regeneration Trust said, “They showed us how we could integrate a natural systems approach into design and development processes in a way that connects people to place, and benefits not only environmental health, but also human activities, aesthetic quality, and economic vitality.”

Things Coming Together—Projects

One of the projects that Michael was passionate about was his work with the City of Toronto on the Bring Back the Don Task Force. He and his firm members also worked on the Don River restoration initiatives. The conservation authority was concerned about the constraints of the flooding at the Lower Don. This was limiting redevelopment opportunities that both the City and landowners wanted to realize. Addressing the flooding would provide ecological benefits for wildlife and recreation for residents, while also acting as catalyst in opening up development potential. This resulted in a win-win for everybody. The firms work was foundational in transforming the West Don Lands into a vibrant neighbourhood.

Influence on Your Practice

Carolyn Woodland worked with the firm for 25 years and then moved on to the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) for 17 years. She credits the design philosophy of the firm with informing her work at TRCA. The award-winning Living City Policy that she developed with her team at TRCA took those foundational principles to the next level and broke new ground.

Eha Naylor and Ian Dance worked with the firm from 1980 until 2009, when they were acquired by Dillon Consulting. They have continued to apply the holistic contextual approached to site development and design, and integrating natural systems. They also continue to tackle large scale projects, such as Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway in Windsor, Ontario, with the same principles.

David Leinster joined the firm in 1986 and moved on to The Planning Partnership in 2000. David described how the practice was never a job for Michael: “He was always on.” David, too, considers his work a “calling,” not a job. He was also inspired to give back to the profession in volunteering his time.

Legacy

Michael elevated the role of landscape architects in Canada. The innovations and design thinking that he fiercely advocated are now an integral part of professional practice. The vision he had for the neglected places such as the Don River and the waterfront have become vibrant spaces enjoyed by the city residents. He trained four generations of professionals and influenced their thinking. He also empowered the women in his firm to excel and lead. A large archival record of his writings, sketches and projects are at the Archives of Ontario and available to the public.

Ken Greenberg, his fellow city builder credits Michael with raising people’s consciousness to the importance of nature in a city and influencing a new generation of landscape architects such as design firm Public Work and others to pick up his torch.

In his tribute to Michael Hough, Robert Wright said, “We owe Michael a debt that can never fully be repaid, except through our own continued commitment to the issues he so dearly believed in and demonstrated through his work.”

Conclusion

Michael Hough was a pioneer and among the lone voices pushing for the integration of urban ecology in planning. The ideas that he campaigned for then seemed radical, but are now common place. It was Bernard Shaw who said, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” It seems that we have now, as a profession, adapted to Michael’s view.

BIO/ Kaari Kitawi, OALA, is an urban designer at a local municipal office, and Ground Editorial Board Member.

Footnotes

1 Jim Stansbury, Remembering and Celebrating My Years with Michael Hough, January 30, 2013

2 Carolyn Woodland, Michael Hough – Memories and Celebration, tribute 2013

3 Etobicoke Historical Society website – www.etobicokehistorical.com/humber-bay.

4 Suzanne Barrett, Waterfront Regeneration Trust, ENVision – The Hough Group. August 13 2003.