Shattered Patterns: Designing the “New Normal”

Moderated by Dalia Todary-Michael, OALA and Katie Strang

BIOS

Cherise Burda is Executive Director of the Ryerson City Building Institute, where she leads research, engagement and communications strategies to advance urban solutions, including affordable housing, sustainable planning and transportation. She holds an M.A. from University of Victoria in environmental policy, and a BSc. in environmental science and Bachelor of Education, both from University of Toronto. She has authored dozens of publications and is a regular presenter and spokesperson @CheriseBurda

Christopher J. Rutty is a professional medical historian with special expertise on the history of public health, infectious diseases and biotechnology in Canada, earning his Ph.D. at the University of Toronto in the Department of History, with his dissertation on the history of poliomyelitis in Canada. Since 1995, Dr. Rutty has provided a wide range of historical research, writing, consulting and creative services to a variety of clients through his company, Health Heritage Research Services. He also holds an Adjunct Professor appointment in UofT’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, based in the Division of Clinical Public Health, as well as the Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases.

Anne-Claude Schellenberg, OALA, CSLA, is a Principal at CSW Landscape Architects Limited in Ottawa, Canada. She is the former Chair of Landscape Architecture Ottawa, the Eastern Chapter of the OALA.

B. Cannon Ivers is a chartered member of the Landscape Institute and a Director at LDA Design in London, UK. He holds a master of landscape architecture degree with distinction from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD). Cannon is a teaching fellow at the Bartlett School of Landscape Architecture and the author of the book Staging Urban Landscapes: The Activation and Curation of Flexible Public Spaces published by Birkhauser.

Katie Strang is a member of the Ground Editorial Board, and works as a landscape designer and ISA certified arborist at The Planning Partnership. She holds an MLA from the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design. Her work is characterized by research and attention to detail, as well as thoughtful consideration of horticultural traditions and ecological processes, in both urban and rural environments.

Dalia Todary-Michael, OALA, CSLA, is a member of the Ground Editorial Board and a landscape architect, maker and interdisciplinary designer working at the intersection of spatial interaction + experience design, kinetic art, and landscape + urban design. She completed her graduate research at the Bartlett School of Architecture UCL in London, UK where she focused on the experience of nature embodiment in kinetic architecture as a performative agent, rekindling perceptive nuances of liveliness that are fading or at risk of being lost.

Dalia Todary-Michael: In the context of everyone jumping in and out of virtual calls, I want to start by asking how the current pandemic has affected your work or life patterns in significant ways, especially given the novel ways we’re communicating and working in this pandemic.

Christopher J. Rutty: I’m a professional medical historian, so I’ve done quite a bit of media interviews in the last few months: different perspectives on the pandemic, the flu of 1918, and a lot on polio (that’s my specialty area and, in many ways, the closest disease to COVID). The situation is keeping me busy and it’s opened a lot of different perspectives. I’m working with new people, media, and other projects and online conferences have come up.

Cherise Burda: In terms of running a research institute, what’s really struck me is the issues we’ve been championing for years now are even more exposed. We’re dealing with public space, overcrowded parks, and the fact we don’t have enough parkland dedication. All these things that we’ve managed to scrape by on in terms of how we plan, design, and resource our city, we can’t scrape by on anymore. These issues are even more critical. We’ve been working on policies to create missing and gentle- and medium-density affordable housing, and suddenly we have this pandemic response where people want to run to the hills and embrace sprawl. We’re actually seeing municipalities respond and take us back decades. So the work we’re doing is now is suddenly urgent in ways that it wasn’t before. It was aspirational, now it’s immediate.

Cannon Ivers: People are really acknowledging the value of good design, open space, and access to streets. That’s one of the fundamental shifts in cities in terms of urban fabric: how people are using streets, their accessibility to neighbourhood streets in the dense urban core of cities, has been profound. Even things like fatalities involving cyclists and buses wasn’t enough to spark change. But we’re now taking cars out of streets in the City of London—a place of trade, of movement, a circulation corridor for over 2,000 years—and suddenly putting the pedestrian and the cyclist first. It’s exciting to see how we’re going to emerge from this in a strategic and incremental way, and if we can’t hold on to some of these great gains.

Anne-Claude Schellenberg: On a micro scale, talking about work flow and daily life with the pandemic, we very quickly moved to remote work. I saw it coming, freaked out, and called my I.T. guys. It was almost seamless. In fact, our workload increased and we’ve found major efficiencies. There is an expectation that we all need brick-and-mortar offices, but some companies are going completely mobile as a result of the pandemic. It’s not easy for everyone. For friends who live alone, for example, work is also their social space. So I set up a daily online coffee break in my office. It’s optional, anyone can sign in, and we just talk. It helps keep us grounded and together as a group. This all ties into the idea of resilience and building redundancy into systems so that if something happens in one place, it doesn’t have a huge impact on everything else, and we can rebound quickly.

DTM: As designers, we sometimes act as agents of the public, and socially responsible design takes that public into consideration and consults with them. Are we starting to think about novel methods of public engagement, and consulting community groups about how their spaces are going to be designed, throughout the pandemic and beyond?

ACS: I’ve done many projects with the City of Ottawa and they’ve had a really solid online consultation process going for a few years now already. So it’s not new and, in fact, I would argue you would probably tend to get a better response to an online survey, compared to inviting people to the local arena for their feedback.

CI: We’ve seen online platforms where you see people’s real-time engagement, even before the pandemic put us all in our homes and new work environments. Even some of the platforms we use for conferences can be used to engage the audience in a meaningful way, and I can see those being a really powerful tool going forward, if you still have set consultation events where you’re working with the local planning authority and planning departments to reach those community groups. A direct, digital platform might yield answers you may not get in person because people are not as open or outspoken, whereas, if they can just simply hit a button on their phone, it’s a really honest response. I think we’ll also get more meaningful feedback from people about how they want to see their spaces designed because people are now more attuned to the fact that they need these spaces in a way we haven’t seen before—not just to the notion of open spaces, but their quality as well. We’re going to get better responses because people have been educated, through this pandemic, to be able to respond in a way that helps guide design.

CJR: Historically, the whole idea of a park goes back to the mid-19th century and the idea of an escape. Infectious diseases, things like cholera and typhoid, are what really inspired urban planning in the first place. It was all pretty chaotic, especially in North America, until 1830s and beyond. Cholera, especially, forced urban planning to have sewers and so forth. All that was driven by infectious disease management because there was nothing else: the only thing they could do to respond to a cholera epidemic, in particular, was manage the physical space. And that’s where we’re at right now. We’ve gone through three phases. We had the nebulous, pre-germ or miasma theory of disease, where quarantine was the only tool they had. Next was the bacteriological revolution, the germs theory of late 19th to early 20th century, where there were very few vaccines, so a lot of the basic infrastructure and modern urban design we’re used to is based on trying to manage public health. It caused shifts from Victorian ornateness to smooth, hard surfaces, driven by an awareness that germs and microbiological threats were more manageable that way. For the wealthy, it defined the whole design of home spaces, bathrooms, and living rooms. When vaccines were finally more broadly available, into the mid-20th century, the emphasis on physical space and objects declined. Since the ‘50s and ‘60s, where infectious diseases were mostly at bay, we relied on vaccines. But now, suddenly, we’re in a global pandemic with no tools. The only tools we have are physical, so we’re all scrambling to restructure the physical world around the pandemic threat. Until we have a vaccine, we’re back, in many ways, 100 years or earlier, trying to adapt the physical to the medical.

Katie Strang: Is there anything you see on the horizon that could reengage us with that idea of public or park space being part of disease and infection management?

CJR: That’s exactly what we’re doing in a sense. The environment and the physical have been disconnected. People obviously talked about it, previously, but we’re really being forced, through this situation, to recognize why we have parks in the first place. It goes back a long way.

ACS: Though there’s also the advent of the suburbs. Before there was a middle class, we had upper classes in their countryside chalets, and then these urban areas. But with the suburbs, everyone had their own little park. I think the use of parks changed at that point, and now we’re returning to promoting higher density development.

CJR: The density issue is what’s creating the problems with COVID, in particular. We’ve allowed ourselves to get very dense, for a lot of reasons, but now we’re in a situation where that’s actually causing problems. So, how do we de-densify in a smart way? Ironically, the post-war baby boom suburbs is what created the situation with polio, which shifted from endemic to pandemic because that was the ideal situation for polio to become a serious problem. Because of density, it was circulating among infants, who were able to fight it. It was a subclinical disease and rarely moved to the nervous system to cause paralysis. But health standards improved, we became more suburban and spread out, had a lot of kids, and the situation became epidemic. The early, almost universal exposure for infants was becoming delayed by our progress in public health and, when older kids got exposed to the virus at school, when their immune systems were no longer as good at responding to it, we saw more paralysis. So, polio is the kind of ironic undercurrent of the suburban thing.

CB: The issue isn’t so much density, the issue is crowding. It’s not how dense you make it, it’s how you make it dense. You can achieve the same amount of density in a tall building with 300 units as you would distributing throughout an existing urban neighbourhood in the form of apartments, triplexes, mid-rises, things like that. This really helps us advance the conversation about finding medium density, because we’ve been building Toronto and many other cities with two options: tall and sprawl. We’ve been sprawling further away, creating a whole bunch of challenges, and achieving our density targets with very tall buildings in small, hyper-concentrated nodes. Now is an opportunity to be looking at distributing density and looking for possibilities for adding density to our current urban landscape.

We’re also talking about planning and designing our spatial landscape, and we need to have a conversation about how we respond to our vertical city. In Toronto, I know upwards of 50 per cent of residents live in towers, high-rises, condos, and apartment buildings. And while we can think about how we plan for future density, we have a critical issue with people living in these vertical dwellings. One of the things we’re struggling with right now is how to innovate these spaces. There’s an opportunity to change how and where we design our buildings or residences going forward, but, currently, we have to figure out things like elevators. Many people in Toronto can’t even get out of their buildings safely, and there are a lot of high-rise, low-income neighbourhoods where people had challenges with elevators and crowding, even before the pandemic. This situation exposes a lot of challenges around our current and future density.

CJR: The challenge seems to be inequity. That’s what’s generated epidemics in the past, and the worst situations with COVID today in the very crowded nursing care situations, or inner cities where multi-generational families live together like New York City or parts of Italy. That’s where the diseases hit hardest because they thrive in that kind of situation. Pandemics tend to exploit the greatest weaknesses in a society, and COVID’s doing that very well. We have a legacy of built society around us—the big towers, low-rises, suburbs, etc. A lot of what we have right now was built when infectious diseases were not a big problem. We’ve grown up in a vacuum of awareness or understanding of what it’s like to deal with infectious disease, beyond small outbreaks or seasonal flu. COVID’s really thrown that out the window. But we’re stuck with all this stuff, a whole culture that’s very crowd-oriented.

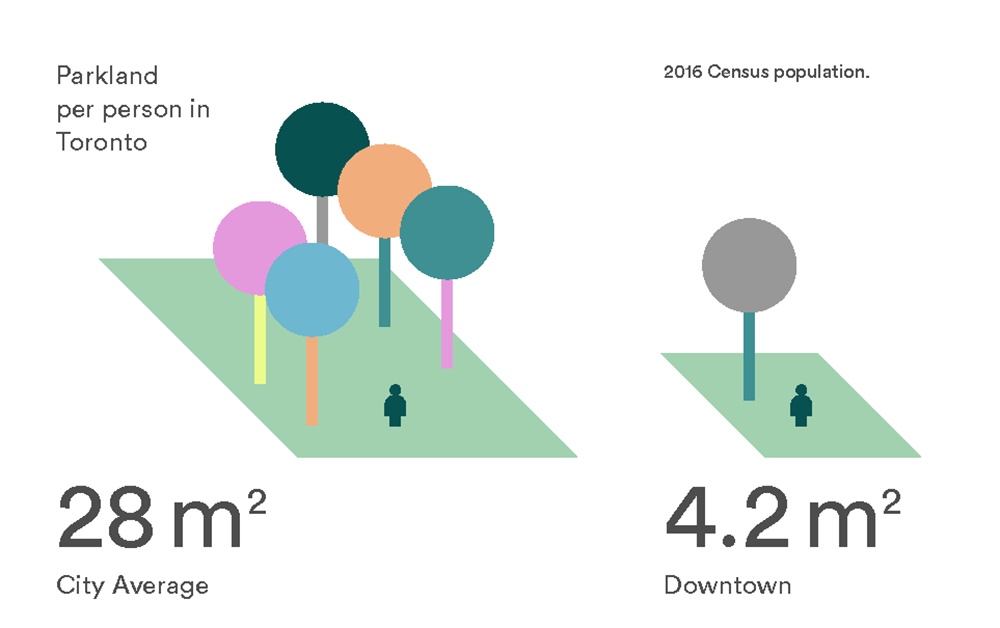

KS: Arguably, we’re seeing that we don’t have enough space downtown, and the per-person amount of parkland seems to be a lot less than we need right now.

CJR: Yeah, anybody with a dog downtown can see that.

CB: There’s 25 per cent less park space per person in downtown Toronto than there is in the surrounding suburbs, not to mention the Greater Toronto Area. In addition to that, people who have more access to park space also typically have backyards, so condo and apartment neighbourhoods are stung twice, without access to either.

CI: My hope, as we start to think about what recovery looks like coming out of this, is to see this against the backdrop of the climate crisis. COVID has taken all the headlines—rightfully so, we’re all adapting to this extraordinary new way of life across the world—but we are also in the middle of a climate crisis. In the UK this year, it’s been the hottest spring on record since the late 1800s. Huge changes are happening that are even bigger than COVID. So we need to be reminded, particularly as those in political power begin to think about how cities come back to life, that the city is one of the most sustainable ways of living. If we can do urban transport well, and encourage active transportation, if some of our most polluted and congested, car-dominated cities can start to adapt and become places for pedestrians and cyclists, then those cities become even more sustainable.

I’m also really fascinated with what the psychological transition time is going to be for us to shake hands again, give each other a hug, or pass each other on the sidewalk without stepping off to the side to give more space. Because, ultimately, I think there’s going to a need to come back to a city where there’s tons of activation playing out in public space. But for that to happen, there’s going to naturally be a transition period where we recalibrate how we come together as a population. I think there’ll be a natural draw to inhabit public space as we did before, but it will take some time.

CB: There are a lot of ways we haven’t been getting cities right that we now have an opportunity to change. Like the cities with hyper-density, rather than with distributed density; housing development that’s developer-driven, rather than community-driven; the lack of public space and how we let that reach a critical point; unaffordable housing; congested commuting and transit overcrowding; sprawl; and the lack of protections for agricultural land and sustainable, locally-grown food. The magic question is how bold are our politicians going to be? I love the fact we’re implementing bigger public spaces for walking and cycling. How permanent will those be when we have a vaccine and say ‘enough bike lanes, let’s get the cars back on the road.’ This is a long game and there’s huge opportunity. I just hope we end up doing some great things in response to this.

ACS: I hope we establish a new normal through this and discard assumptions we had about daily travel: that you have to go to the office every day. We’re seeing the tangible positive effects of taking cars off roads. You can use that to gather momentum for street openings. Unfortunately, here in Ottawa, we’ve just seen an expansion of the urban area. If it’s transit oriented development, okay. But the fear is that it’s just more of the same, and, as we can see, that wasn’t the best for the planet or people’s health.

DTM: I wonder if things like wildlife creeping back into the deserted city is bringing back value that people took for granted, maybe even an understanding of what a resilient, biodiverse ecosystem can offer a city. Is this something you’ve thought about, in terms of future patterns?

ACS: For most of our projects, we’re trying to use primarily native plant material to support local insect and bird populations. If you’re in a dense urban area, is it better to plant a tree that will struggle or a tree that will thrive? Is the tree for shade, or are you trying to help the larger ecosystem? We used to bring in exotic plants, simply because they were exotic. Now, there’s a greater appreciation for native material.

KS: Are there any new patterns you hope become permanently established? Have we learned anything from this pandemic?

CI: Recovery is going to happen in our public spaces. The fact we have an abundance of streets and parks that haven’t been used to their potential is going to be the roadmap for how we come out of COVID. I just hope we’re adaptive and able to respond. It’s amazing how quickly we’ve been able to adapt to an entire new way of life, how quickly technology has allowed us to do what we’re doing here, and how readily we can share knowledge. My hope is that we don’t lose that. And that we respond, rather than just react.

CB: It’s not as though we don’t know how to change. We don’t want to change. But we’ve seen a rapid response from cities all over the world that are redesigning their right-of-ways to accommodate cyclists and pedestrians. Is that going to be permanent? There’s opportunity to use this as a huge pivot point. In my lifetime, I haven’t seen us adapt and change this quickly. We should remember this the next time we’re pushing through some big, important planning or design change.

CJR: It’s a good opportunity for designers to start thinking again through a public health lens. Because the situation will be an ongoing issue for a while. Some other threats don’t give us this chance, because they’re more short-term or localized, and we’re not forced to think about something new.

ACS: I agree it’s an opportunity. It’s made us stop and question our behaviours and change quickly. We also have an opportunity to define our priorities: our ability to have a local economy and be self-sufficient, while also maintaining global relationships; the importance of green space; opening roads and creating cycling facilities and shared streets. As bad as a pandemic is, I think it’s given us chance to reset, especially for designers. This is stuff we’ve all been talking about and has always been a priority for us, but we have a bigger audience now.

CJR: Pandemics do that. It’s happened on several occasions over past centuries, in different parts of the world. Major epidemics force changes. They force people to think in a different way, at least for a short term, and that, in turn, creates new challenges.

ACS: All hail the new normal.