Round Table: A seat at the table

The challenges and rewards of championing landscape

MODERATED BY LE’ ANN SEELY

BIOS/

CAROLYN WOODLAND, OALA, FCSLA, MCIP, RPP, JOINED THE TORONTO AND REGION CONSERVATION AUTHORITY (TRCA) IN 2002. AS THE FORMER SENIOR DIRECTOR, PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT AT TRCA, SHE DIRECTED THE ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING, DEVELOPMENT REVIEW, POLICY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FUNCTIONS WITHIN 18 MUNICIPALITIES IN THE JURISDICTION. AS A LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT AND URBAN PLANNER, CAROLYN’S SIGNIFICANT WORK HAS HELPED TO PROTECT ONTARIO’S FUTURE BY DEFINING POLICIES AND PLANS TO MANAGE GROWTH, PROTECT AND ENHANCE GREENSPACE, PROTECT WATERSHEDS, AND FOCUS ON CLIMATE CHANGE.

CLAIRE NELISCHER HAS A BACKGROUND IN URBAN PLANNING, PUBLIC POLICY, AND CIVIC PROCESS. SHE IS A PROJECT MANAGER WITH THE RYERSON CITY BUILDING INSTITUTE, WHERE HER WORK FOCUSES ON PLANNING AND POLICY TO SUPPORT A VIBRANT PUBLIC REALM. SHE HAS AUTHORED REPORTS ON A RANGE OF TOPICS INCLUDING STREET DESIGN, PARKS POLICY, AND PLANNING FOR CIVIC ASSETS. SHE WAS AN URBAN FELLOW WITH THE CITY OF TORONTO, WHERE SHE CONTRIBUTED TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY’S FIRST COMPLETE STREETS GUIDELINES. SHE HOLDS A M.SC. IN CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING FROM PRATT INSTITUTE AND A BAH FROM QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY.

CHRIS GLAISEK IS THE CHIEF PLANNING AND DESIGN OFFICER AT WATERFRONT TORONTO AND IS A PASSIONATE ADVOCATE FOR DESIGN EXCELLENCE IN THE PUBLIC REALM. HE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR CONCEIVING PLANNING AND DESIGN INITIATIVES AND MANAGING DETAILED DESIGN FOR WATERFRONT TORONTO PROJECTS IN THE 2,000-ACRE DESIGNATED WATERFRONT AREA. UNDER CHRIS’S STEWARDSHIP, WATERFRONT TORONTO HAS RECEIVED MORE THAN 60 NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR ITS MASTER PLANS, PARKS, AND STREETSCAPE DESIGNS.

NINA-MARIE LISTER IS GRADUATE PROGRAM DIRECTOR AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING. FROM 2010-2014, SHE WAS VISITING ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN. SHE IS THE FOUNDING PRINCIPAL OF PLANDFORM, A CREATIVE STUDIO PRACTICE EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LANDSCAPE, ECOLOGY, AND URBANISM. LISTER’S RESEARCH, TEACHING AND PRACTICE FOCUS ON THE CONFLUENCE OF LANDSCAPE INFRASTRUCTURE AND ECOLOGICAL PROCESSES WITHIN CONTEMPORARY METROPOLITAN REGIONS, WITH A PARTICULAR FOCUS ON RESILIENCE AND COMPLEX, ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS DESIGN. AT RYERSON UNIVERSITY, LISTER FOUNDED AND DIRECTS THE ECOLOGICAL DESIGN LAB.

EHA NAYLOR, OALA, FCLSA, IS A PARTNER AT DILLON CONSULTING AND LEADS THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN PRACTICE NATIONALLY. SHE HAS OVER 30 YEARS OF CONSULTING EXPERIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND SITE DESIGN FOR BOTH THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS, AND EARNED NUMEROUS PROFESSIONAL AWARDS. SHE IS A MEMBER OF SEVERAL PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS INCLUDING THE ONTARIO PROFESSIONAL PLANNERS INSTITUTE, AND THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS. IN 2000, SHE WAS NAMED FELLOW OF THE CANADIAN SOCIETY OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS AND RECEIVED THE ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS PINNACLE AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT IN 2013.

JASON THORNE LEADS THE PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT AT THE CITY OF HAMILTON. HE OVERSEES A TEAM OF 800 STAFF WORKING ACROSS MULTIPLE PORTFOLIOS INCLUDING PLANNING, BUILDING, DEVELOPMENT ENGINEERING, TRANSPORTATION PLANNING, PARKING, ARTS, CULTURE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. JASON’S DEPARTMENT TOUCHES ON ISSUES OF HOUSING AND AFFORDABILITY. THIS INCLUDES LEADING THE CITY’S PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT APPROVALS FUNCTION, WHICH DIRECTLY AFFECTS LAND AND HOUSING SUPPLY, AND DEVELOPING PLANNING AND FINANCIAL POLICIES TO SUPPORT AFFORDABLE HOUSING. BORN AND RAISED IN HAMILTON, HE HAS BEEN WORKING IN PLANNING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT HIS ENTIRE CAREER. HE WAS MANAGER WITH THE ONTARIO GROWTH SECRETARIAT AND DIRECTOR OF POLICY AND PLANNING WITH METROLINX.

LE’ ANN SEELY, OALA, IS A GROUND EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBER AND PRINCIPAL AT WHITEHOUSE DESIGN GROUP INC.

Le’ Ann Seely: In what situations have you found landscape architects have the primary power of influence over the outcome of a project? What do you think was the main reason they had that power?

Nina-Marie Lister: This tends to happen in unusual projects, or projects that are highly integrated. They’re not strictly in the domain of the development planner, or where the landscape architect is reduced to landscape decorator. These are powerful projects of integration, across different sectors. Waterfront Toronto is certainly a place where we’ve seen landscape leading, and not just because the physical lie of the land is a landscape, but rather the development potential is a different vision of the city, where landscape is infrastructure and the infrastructural investment requires a speciality beyond the traditional approach to planning and development.

Chris Glaisek: I think part of the power of landscape architecture is bringing design thinking to a problem. When the landscape architects bring that power, it transforms how people look at possibilities, how people look at what’s in their daily life that they’ve never paid attention to before, and suddenly they’re thinking about it and interpreting it and seeing some meaning or cultural messages in it. I think landscape architects are bringing a much more conscious and premeditated way of looking at the landscape that centre different, important issues: environmentalism, ecology, systems thinking, nature, health. It’s all embedded in what landscape architects do. To me, the real power is when you unveil a really good landscape design, it changes how people perceive the world of possibilities.

Carolyn Woodland: I can see from the work I’ve been doing for the last 20 years that there’s a gap between policy, and what we think we’re doing in our policy, and the engineering technical side of regulations and standards. They don’t come together easily. A landscape architect, and thinking about landscape, is actually quite powerful in terms of problem solving. Whether it’s an urban design scenario, a water management scenario, a restoration of a landscape—those components can be brought together and you can have some added value to it. The power is how it’s conveyed, and how you communicate it with other people. I find people struggle with communications, and a skilled landscape architect can help bridge those communications as well.

Jason Thorne: To me, “power” suggests the ability to do unilateral decision making. And I’m not sure any discipline should be in the position of being able to exercise power in unilateral decision making. When I heard “power” I kind of took it as creative control. So when does a landscape architect largely have creative control over an outcome. I would say, in my experience, unfortunately, the answer is not often and probably not as often as should be the case. Where I have seen it in my experience, it tends to be in situations where there’s not other considerations that are crowding out that exercise of creativity. Generally, it’s public sector-driven projects. If there’s competing demands on space from your traffic engineers then that becomes the dominant paradigm that’s going to drive your design thinking. Or if it’s a built form. Or, even if it’s ecological restoration, those can kind of crowd out the exercise of landscape architecture. Unfortunately, landscape architecture typically only dominates when it is a project or canvas that is uncluttered by other considerations. Once those other considerations come into play, I think landscape architecture quickly takes a back seat.

Claire Nelischer: I think there is a growing recognition of the importance of our public spaces and landscapes, and a growing recognition of those places as landscapes themselves and not just leftover spaces between buildings. That’s a really powerful concept, and I’m not sure how that translates into the decision making power of landscape architects, or how they engage with other professions and collaborative projects. But as a way of thinking about how landscapes and how the work of landscape architects fit into the broader city building endeavour, understanding how landscapes themselves are becoming more and more important to people and are recognized as such demonstrates the increasing power that we’re affording to this practice and to these concepts and how they might influence the cities we live in.

N-ML: We are sitting on the edge of the Anthropocene at a time when there are more people living in cities than ever before in history. Our cities are growing faster than ever. So, it stands to reason that on the climate crisis moment, and the biodiversity crash around us, the urban landscape will be the only landscape our children will ever know. That’s a really powerful thing to think about. It gives a huge weight of responsibility and opening for landscape architecture to make and remake those landscapes. As we have less of what we recognize today as a naturalized landscape, it becomes more important. I think we are very well poised and perhaps burdened by the urgency and the moment to take advantage of investment in landscape as infrastructure.

JT: I think, increasingly in the future, we’re going to have less ability to rely on the private realm to satisfy certain needs: the backyard, the larger homes. As people live in smaller and smaller footprints, the public realm becomes that much more important. Peoples backyards are going to be the public realm. That puts a lot of responsibility on landscape architects to design in such a way that you’re meeting the needs of a whole lot of different people who need that space for various different reasons.

CG: We have this huge outdoor deficit in our society. I heard a statistic that the average child now spends seven minutes outside each day and seven hours on the screen. If that’s true, landscape needs to be more; it actually needs to find a way to draw those people back out into the landscape. Landscape architects really have to find a way to capture people’s imaginations and get them to want to come back outside. It’s a tough job to compete with screens and a virtual world on our phones. They’re shown to be addictive, and I’m not sure if nature has been shown to be as addictive as screens are. Maybe we need to think about how we approach it and how we talk about it in a way that gets people wanting to participate in it. And I think it’s going to be the landscape architects who will figure this out.

N-ML: The statistics are overwhelming. Yet we, as a human species require nature. It’s biophilia: this idea that nature, or the living landscape, designed or otherwise, is in our genes. It’s in our blood and we need it. This means the real agency of landscape architects is to capture people’s imaginations. This idea that we have the capacity to show and to give sensation and realization and legitimacy to those landscapes is absolutely paramount. We know that living landscapes are essential for physical wellness, for mental health and wellbeing.

Eha Naylor: These landscapes are being asked to do a lot by a lot more people, and we’re using a framework for protecting them which I think is outdated. Here we have climate change: it needs to be the vessel for resiliency. We have issues related to people’s wellness, living in intensified areas, and these are places that we need to be able to seek refuge in. We’re protecting them with very archaic tools, and we’re not acknowledging, yet, how instrumental they are to survival in urban environments.

CW: There’s a big role for professionals in selling how important it is to the politicians who, in a lot of cases, if you look at where growth is coming, don’t understand the importance of nature, because we’re so pressed right now to develop every inch. We need to build the argument of how that value is there. When you look at who’s out there in municipalities, landscape architects are working in these areas, but they haven’t got the power to be strong in those situations. We can’t just keep telling each other that it’s important. You have to get out there.

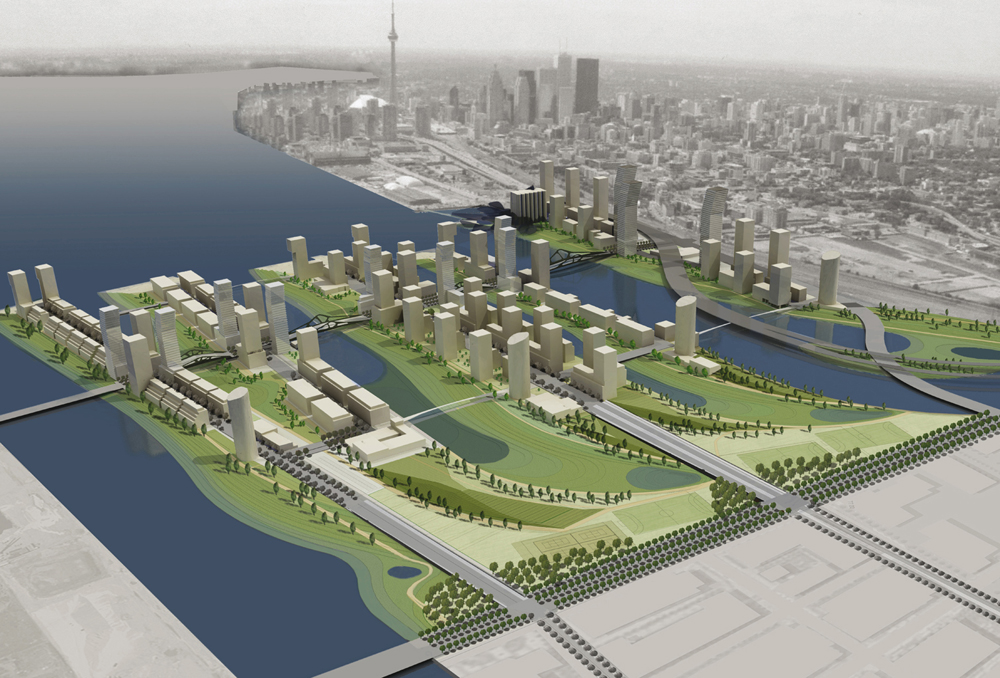

N-ML: Good design can successfully solve a number of different challenges. Which is why, when you lead with landscape architecture in a large public project, you are able to satisfy multiple objectives. Waterfront Toronto is an excellent example where, not so long ago, the Portlands were the city’s back porch where you threw the junk. And now it’s once again returned, metaphorically and physically, to look at the water, through good design, to make accessible the city’s front porch. That only works if it’s tied in, up the ravines to the headwaters, to those great protected areas. And it is, in that sense, intended to be a functioning, well designed system. But if you fragment it and break it into smaller development parcels, without an eye to the value of the whole landscape system, all that effort, investment, and good design on waterfront doesn’t mean much.

CG: Getting ecology, flood protection, and urbanism to all co-exist was a challenge for all the disciplines involved. I think landscape architects bring a convergent thinking to problem solving as opposed to divergent thinking. In the case of the Don River, one of the main factors was putting the landscape architect at the top of the pyramid, which is not conventional and was a fairly controversial move, and I had to fight pretty hard to convince people it was a good thing to do. But when they’re in the driver’s seat with the engineers and hydrologists and all those others, that leads you to those convergent solutions. Having the conviction to put them at the top and treat them the way you would treat an architect. No one would ever hire an engineer and say ‘design the structural system for my building first and then I’ll bring the architect in to design the building.’ Everything would turn out wrong. But that’s exactly how we design landscapes, typically. You bring the civil engineer in and then the landscape architect comes in at the end and you’ve got the cart before the horse. So inverting that, I think is the right way to go. But it’s a very difficult sell.

LS: In what situations have you found landscape architects have not had the primary power of influence on the outcome of a project, despite the scope of work falling within what is performed by landscape architects elsewhere? Why do you think these situations occur and how do we fix it?

N-ML: A lot of these issues of influence come down to procurement, particularly through public realm projects. Or that may be a symptom. The real cause may also be that you have decision makers in charge who don’t understand the role of landscape architects. It’s not visible to them. They only hear the first word, landscape, which they interpret as ‘bring in the landscapers and they’ll put some shrubs.’ I hear that many times from my colleagues: that they’re asked to add the nature band-aid after the development is done.

CN: I think that’s a challenge in a lot of the design disciplines: when a design is done well, you don’t see the labor behind it. That leads to people discounting the necessity of that work from the outset. That’s a huge problem in street design, which is something I’m particularly interested in. When everything is working well and it’s engineered within an inch of its life, then you as a user of that street do not see all of the detail that goes into that work.

JT: Street design’s a great example. Why aren’t more landscape architects project managers on street design? Typically, far too often, the outputs that are valued most are, first we’ve got to have our parking, and our traffic flow, bike lanes, wayfinding components, and then storm controls. Then, finally, the landscape architect can plant some bushes in the spaces left over. Each of these things have staunch advocates arguing for them. There’s not a strong advocate for getting the landscape right.

EN: The challenge is to be able to be articulate, intelligent, and experienced enough to make the case that we should leading these exercises. Or at the very least, be at the table from the beginning. In my role as the Chair of the Practice Legislation Committee, we do butt up against engineers and architects who are regulated and look at landscape architects and say ‘well, you may have these skills, but you’re still not a regulated profession.’ To be recognized as having skills and experience that is equivalent to architects and engineers—we have to advocate for that. That said, I don’t think there’s been a better time to be a landscape architect. With crisis comes opportunity. We have a climate change crisis, but for landscape architects it is an opportunity to actually be able to grow a voice and demonstrate our skills. And to help our communities be places that are more resilient. I think it’s a fantastic time.

CW: Decision makers need waking up. They need to be told over and over again what, and how exciting the landscape could be, whether it’s an urban streetscape or a major new park.

CG: One of the biggest risks I see to all of this opportunity is fiscal constraints. Not just in terms of capital dollars, but in terms of what people are willing to pay for design.

EN: So the problem can be solved by educating those who are setting budgets to set appropriate budgets. Those in the position of setting budgets and determining what the quality of the design is should know that you get what you pay for.

JT: Quite often what you’re faced with is ‘we can do five parks at an okay design or we can do four parks and invest heavily in design.’ Well, someone’s not getting a park if you go for the excellence in design option. Often that’s the debate, and conversation just ends there.

N-ML: Then we shift the conversation, and look to landscape architecture to show where ecological performance and social value benefits are being accrued, and the public says, ‘wait a minute, we want that.’ That’s the conversation that needs to happen and it is part of the burden and responsibility of the profession and allies to make visible those benefits to a public who will demand them.

CW: I did educate people about that value and how important it is, and it got documented in the Living City policies, and in presentations. Over time in your career, you can do those things if you consciously move in that direction.

N-ML: Sharing the stories.

EN: You have to be loud to be heard. I think it’s time, at every level, for landscape architects to talk to those who hold the purse strings and make decisions about how beneficial the knowledge of landscape architects is to creating a better place. A more resilient place, a happier place.

THANKS TO NADJA PAUSCH FOR HELP COORDINATING THIS ROUND TABLE.